CENTERFORBENEFIT‐COSTSTUDIESINEDUCATION,

TEACHERSCOLLEGE,COLUMBIAUNIVERSITY

BENEFIT‐COSTANALYSISOF

ACCELERATEDSTUDYIN

ASSOCIATEPROGRAMS(ASAP)

OFTHECITYUNIVERSITYOF

NEWYORK(CUNY)

HenryM.LevinandEmmaGarcia

May2013

ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to extend thanks to the following individuals for their assistance in the

development of the study and preparation of this report: Brooks Bowden, Research Associate at

the Center for Benefit-Cost Studies of Education (CBCSE); Donna Linderman, CUNY Associate

Dean for Student Success Initiatives and ASAP University Executive Director; Colin Chellman,

CUNY Associate Dean for Institutional Research; Zineta Kolenovic, CUNY ASAP Assistant

Director for Evaluation and Research; and Simon McDonnell, CUNY Senior Policy Analyst.

Special thanks to the New York City Center for Economic Opportunity (CEO) for their support

of this study.

iii

ABOUTTHECENTERFORBENEFIT‐COSTSTUDIESOF

EDUCATION(CBCSE),

TEACHERSCOLLEGE,COLUMBIAUNIVERSITY

The Center for Benefit-Cost Studies of Education (CBCSE) conducts research on the benefits

and costs of alternative educational policies and interventions.

Education is a social investment that entails both costs and outcomes.

Too often assessments of educational alternatives either ignore their costs or calculate them in

inappropriate ways. Similarly, benefits of education are often viewed too narrowly or measured

inappropriately.

The CBCSE brings together scholarship on both benefits and costs so that the full value of

investments in education can be evaluated, and the most productive use of resources can be

chosen.

The Center also undertakes cost-effectiveness studies to ascertain the types of educational

interventions that will produce educational outcomes at least cost.

For more information visit: http//www.cbcse.org/.

1

ABSTRACT

This study evaluates CUNY’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) from a

benefit-cost perspective. ASAP is designed to accelerate degree completion within three years at

community colleges. This report builds on the CUNY evaluations of ASAP, which provide

consistent evidence for the dramatic success of ASAP on increasing the timely completion of

associate degrees. Although ASAP requires more resources per student than the traditional

associate program, the cost per graduate was found to be lower because of its much higher

effectiveness in producing graduates.

The benefit-cost analysis of ASAP enables us to calculate the monetary costs and benefits

of this intervention with particular emphasis on the financial returns to the taxpayer. We estimate

the benefits arising from higher tax revenues and lower costs of spending on public health,

criminal justice, and public assistance and compare them with the required investment for ASAP.

The estimates show that there are large financial returns on ASAP investment for the taxpayer

and for the students in the program. In all cases, the benefits exceeded the costs. For each dollar

of investment in ASAP by taxpayers, the return was between three and four dollars and around

twelve dollars for each dollar invested by the individuals, suggesting that ASAP is a very

productive public and private investment. When applied to the much higher ability of ASAP to

produce high graduation rates, the overall returns to the taxpayer are impressive. A cohort of

1,000 students enrolled in ASAP would generate fiscal benefits for the taxpayer beyond

investment costs of more than $46 million, a very substantial monetary return for this

educational intervention.

2

LISTOFTABLESANDFIGURES

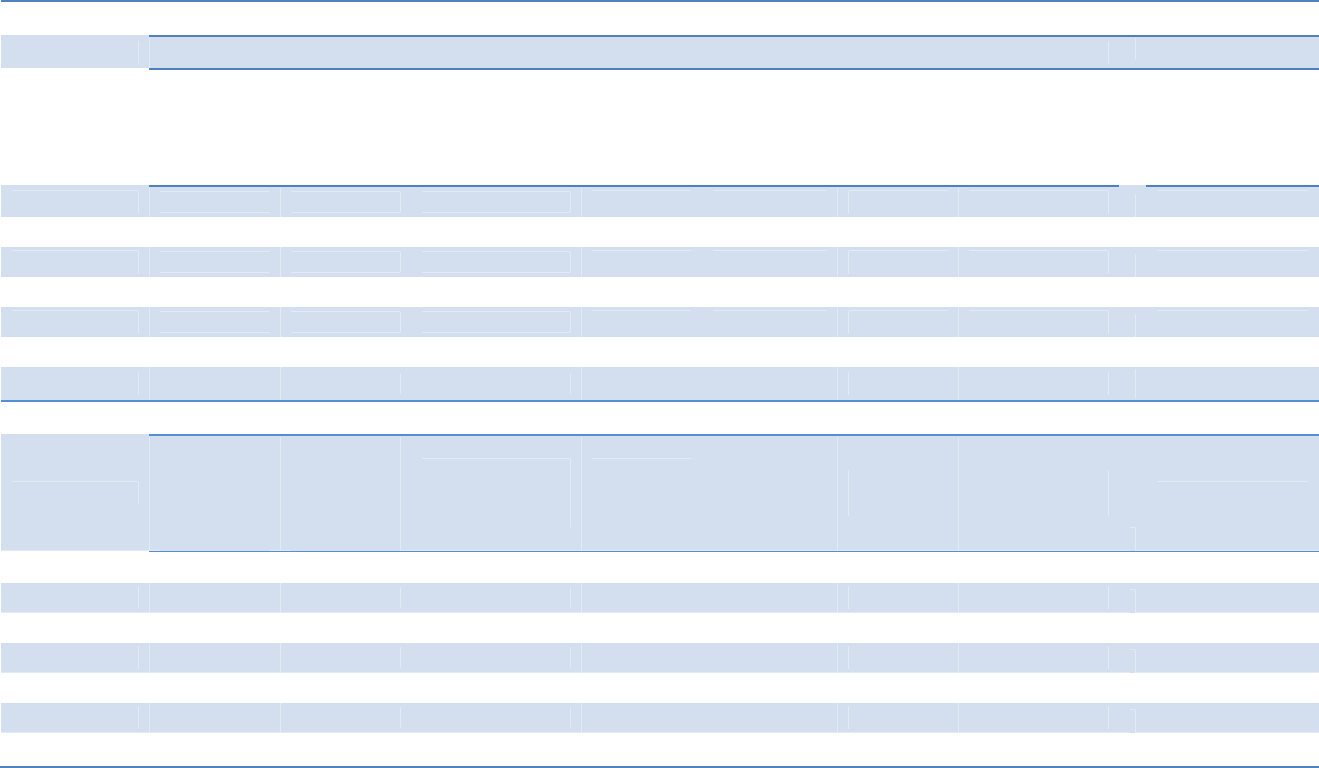

Table ES1: Lifetime Earnings by Educational Attainment. Breakdown by Gender, and Ethnicity

(Present Value at Age 23 at 3.5 Percent Discount Rate), 2008-10

Table ES2: Generation of Total Fiscal Benefits to the Taxpayer per Degree (Present Value of

Lifetime Benefits at Age 23)

Table ES3: Benefits to Cost Comparisons for the Taxpayer: Total Institutional Costs versus Direct

Benefits

Table ES4: Net Present Value of the Taxpayer Investment for 1,000 ASAP Enrollees versus

1,000

Traditional Students

Table ES5: Net Benefits for the Student: Total Student Costs versus Benefits

Table 1: Total Institutional Cost per Graduate

Table 2: Employment and Unemployment Rates, and Economically Active Population

(% in the Labor Force)

by Educational Attainment, 2010

Table 3: Lifetime Earnings by Educational Attainment. Breakdown by Gender, and Ethnicity

(Present Value at Age 23 at 3.5 Percent Discount Rate), 2008-10

Table 4: Lifetime Earnings, City, Property and Sales Taxes by Educational Attainment.

Breakdown by Gender and Ethnicity (Present Value at Age 23 at 3.5 Percent Discount

Rate)

Table 5: Lifetime Earnings, City, Property and Sales Taxes: Comparison by Educational

Attainment. Breakdown by Gender and Ethnicity (Present Value at Age 23 at 3.5 Percent

Discount Rate)

Table 6: Health Coverage Indicators by Educational Attainment

Table 7: Health Coverage Indicators by Educational Attainment. Breakdown by Gender and Race

Table 8: Lifetime Public Health Expenditures, by Educational Attainment (Present Value at Age

23 at 3.5 Percent Discount Rate)

Table 9: Welfare Assistance by Educational Attainment

Table 10: Lifetime Welfare Income, by Educational Attainment (Present Value at Age 23 at 3.5

Percent Discount Rate)

Table 11: Proportion of Incarceration and Participation in Other Crime-Related Activities

Table 12: Lifetime Crime Costs, by Educational Attainment (Present Value at Age 23 at 3.5 Percent

Discount Rate)

Table 13: Generation of Total Fiscal Benefits to the Taxpayer per Degree (Present Value of

Lifetime Benefits at Age 23)

Table 14: Benefits to Cost Comparisons for the Taxpayer: Total Institutional Costs versus Direct

Benefits

3

Table 15: Net Present Value of the Taxpayer Investment for 1,000 ASAP Enrollees versus 1,000

Traditional Students

Table 16: Total Costs Per Graduate, Comparison Group and ASAP Group: Breakdown per

Constituent (Student), for Three Years

Table 17: Net Benefits for the Student: Total Student Costs versus Benefits

Table A1: Summary of Sources of Information

Table A2: Tax Revenue Gains for Married People

Table A3: Lifetime Earnings, City, Property and Sales Taxes by Educational Attainment (for

Married People)

Table A4: Lifetime Earnings, City, Property and Sales Taxes by Educational Attainment: Single

Minus Married

Table A5: Approximate Distribution of the Benefits by Government Level

Figure 1: Average Earnings and Years of Schooling, 2008-10

Figure 2: Age-Earnings Profiles by Educational Attainment, 2008-10

Figure 3: Federal, State, and FICA Age-Income Tax Profiles by Educational Attainment, 2008-10

Figure 4: Proportion of CUNY’s Associate Graduates Currently Residing in New York State and

New York City by Graduation Year, 1981-2008 (in Percentages)

4

EXECUTIVESUMMARY

In 2009 more than 7.5 million students were attending community colleges in the U.S.

(Bureau of the Census, U.S. Department of Commerce 2012), however, only about 22 percent of

students who enrolled in community colleges completed an associate degree within three years

(Snider & Dillow 2011), and completion rates were even lower in urban institutions. A separate

analysis of a national database by the CUNY Office of Institutional Research and Assessment

(OIRA) has found that only 16 percent of students at urban community colleges graduate within

three years.

In recognition of this challenge, the City University of New York (CUNY) established a

comprehensive program to assist students to complete their associate degrees with support from

the New York City Center for Economic Opportunity (CEO). This program, known as

Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP), aims to graduate at least “…50 percent of

students within three years through provision of comprehensive support services and financial

resources that remove barriers to full-time study, build student resiliency, and support degree

completion” (Linderman & Kolenovic 2012: 9).

The results have been immediate and impressive; ASAP has more than doubled the

number of associate degrees in three-years compared with the results of a matched group of

similar students who did not benefit from ASAP services. The program has been considerably

more effective at graduating students than conventional community college experiences. But,

given the fact that ASAP requires additional financial resources, two questions arise: 1) Is ASAP

more cost effective than the conventional approach? and 2) Does the investment return greater

benefits to the taxpayer than its costs?

In a previous cost-effectiveness study

1

we asked whether the larger number of graduates

is sufficient to compensate for the additional resource costs (Levin & Garcia, 2012). In that

study, we compared the institutional costs per associate degree completion of students in ASAP

with that of a comparison group of similar students who did not participate in ASAP. This

comparison revealed that the cost per three-year graduate with an associate degree was actually

lower for ASAP than for the comparison group. Although the program costs per student were

greater, the increase in the number of three-year graduates was so substantial that the cost per

completed degree for ASAP students was about $6,500 less than for the comparison group.

The report that follows evaluates the returns on the investment in ASAP by comparing

the value of monetary benefits to taxpayers and students relative to the monetary costs that each

constituency pays. Benefit-cost analysis enables us to ascertain whether an investment in ASAP

is “worth it” in terms of benefits exceeding costs. In the case of improving educational success,

there are obvious benefits to the student in terms of better employment and job opportunities and

improved options for further education, as well as better health, greater knowledge, and the

1

http://www.cuny.edu/academics/programs/notable/asap/about/evaluation/Levin-ASAP-Cost-Effectiveness-

Report.pdf

5

ability to learn new things. There are also benefits to the taxpayers who pay much of the cost of

investment in education. By increasing the numbers and quality of educated persons, society

gains from higher economic productivity and income, as well as greater technological advance

and inventive activity. Government and taxpayers also experience fiscal benefits in higher tax

revenues and lower demand for and costs for spending on public health, criminal justice, and

public assistance (Belfield & Levin 2007a). This report compares the benefits and costs of the

additional associate degrees produced by ASAP to ascertain if the benefits exceed costs and to

estimate the magnitude of those differences. That is, we focus specifically on whether taxpayer

investments in producing additional associate degrees at CUNY community colleges through

ASAP will produce taxpayer benefits that are equivalent or greater. The basic method draws

upon traditional analysis of investment in human capital (Becker 1964), which was first applied

to specific educational policies by Levin (1972) to calculate the benefits of specific educational

interventions relative to their costs.

BenefitsofAssociateDegreeCompletion

We calculate the benefits of completing an associate degree for the student and the

taxpayer by considering the benefits of higher earnings; income tax contributions, property taxes,

sales taxes, local income taxes, and the reduced costs of public services for crime, public health,

and public assistance.

SummaryofStudentBenefits

Table ES1 shows the present value

2

of lifetime earnings for high school and associate

degree recipients by gender and race. The average for the overall group is based upon the overall

composition of the New York City population, on the premise that CUNY community college

enrollments should ultimately be ethnically similar to the city. The advantage in present value of

lifetime earnings for the associate degree over high school completion is substantial, varying

from about $310 thousand to about $362 thousand, depending upon the group. This is a

substantial lifetime premium for an associate degree. Present value in this table can be thought of

as the equivalent of a certificate of deposit (CD) that pays 3.5 percent a year in interest over a

lifetime.

2

For specific details, see detailed information in the report (Levin & Garcia, 2013).

6

Table ES1: Lifetime Earnings by Educational Attainment. Breakdown by Gender, and

Ethnicity (Present Value at Age 23 at 3.5 Percent Discount Rate), 2008-10

HS Associate

Associate minus HS

Total 640,330 964,472 324,142

Male 790,064 1,128,983 338,919

Female 485,903 848,132 362,229

White 792,455 1,128,714 336,260

Black 616,739 926,892 310,153

Hispanic 566,767 869,654 302,887

Other 532,962 857,746 324,784

Source: Authors’ calculations based on American Community Survey (ACS) 2008-2010. Productivity increase per

year: 1.5 percent. In constant 2010 dollars.

SummaryofTaxpayerBenefits

Table ES2 provides a summary of the direct fiscal benefits to the taxpayer for producing

an additional associate degree. Most of the benefits are generated from the additional tax

revenues of associate degree recipients, amounting to a present value at age 23 of about

$165,000 (or 80 percent). However, there are also substantial benefits from reduced costs of

public health, public assistance and criminal justice, amounting to about $40,000 (or 20 percent).

Overall, each additional associate degree provides fiscal benefits to the taxpayer of $205,000 in

present value of lifetime benefits at age 23, the equivalent of giving a gift of a certificate of

deposit to taxpayers of this amount. That is, the achievement of an associate degree by high

school completers provides considerable relief to taxpayers in higher tax revenues and lower

public spending over the lifetime of the associate degree recipient.

Table ES2: Generation of Total Fiscal Benefits to the Taxpayer per Degree (Present Value

of Lifetime Benefits at Age 23)

Per Additional Associate Degree

Total Public Benefits $205,514

Tax revenues from income

a

$145,567

Property and sales taxes $19,833

Savings-health expenditures-public

b

$5,026

Savings-Welfare and public assistance $5,956

Savings-Criminal Justice $29,132

Note: a: Includes Federal, State, FICA, and City Income taxes; b: Includes Medicare, Medicaid, VA, TRICARE,

Other Federal, State, and Local Sources, and Other Public. For specific sources of information, see detailed

information in the report (Levin & Garcia, 2013). In constant 2010 dollars.

7

NetBenefitsofAssociateDegreeCompletion

NetBenefitsofASAPfortheTaxpayer

Although there are considerable benefits to the taxpayer from this investment, it is

important to deduct the investment cost to produce an associate degree. There are two ways to

express this comparison. The first is to subtract the cost of the taxpayer investment for

increasing the number of associate degree holders from the taxpayer benefits produced by the

additional associate recipients. Do the benefits exceed the costs, and by how much? A second

way is to establish the ratio of benefits to costs to ascertain the dollar return in benefits for each

dollar of costs. Table ES3 shows the net benefits to the taxpayer after costs are accounted for, as

well as benefit-cost ratios.

Table ES3: Benefits to Cost Comparisons for the Taxpayer: Total Institutional Costs

versus Direct Benefits

Benefits per

Additional Degree

(Taxpayer)

Institutional Cost per

Graduate (Taxpayer)

Benefits Minus

Costs (Net Benefits)

(Taxpayer)

Benefit/Cost

Ratio

(Taxpayer)

Fall 2006

Comparison

Group

$205,514

$65,884

$139,630

3.1

Fall 2007

ASAP Cohort

$205,514

$59,302

$146,212

3.5

In constant 2010 dollars.

The impressive return to the public investment for each graduate, does not take account

of the massive increase in graduate completion of ASAP. ASAP has a three-year graduation rate

of almost 55 percent, in contrast to only about 24 percent for the traditional program. If 1,000

students enter the traditional program, about 241 would be expected to graduate in three years. If

1,000 students enter the ASAP program, we would expect more than twice as many, about 549,

to graduate. As shown in table ES4, the total net benefits associated with the initial enrollment

of 1,000 students in ASAP are about $46,000,000 higher than the net benefits associated with a

similar initial enrollment for the comparison group.

8

Table ES4: Net Present Value of the Taxpayer Investment for 1,000 ASAP Enrollees versus

1,000 Traditional Students

Enrollees

Graduates per

1,000 Enrollees

Net Benefits per

Graduate

Total Net

Benefits per

1,000 Enrollees

Comparison Group

1,000 241.2 $139,630 $33,678,756

ASAP Cohort

1,000 548.6 $146,212 $80,211,903

Difference (ASAP-Comparison)

$6,582 $46,533,147

In constant 2010 dollars.

Total net benefit associated with actual current 2012/13 CUNY ASAP enrollment (2,200

students), is estimated to be $102,000,000 over and above a similar comparison group

enrollment. This is a sizable advantage in the impact in favor of ASAP, as well as providing

considerably higher efficiency in assisting community college students to complete their studies,

a winning strategy for students, taxpayers, and CUNY.

NetBenefitsofASAPfortheStudents

The total direct benefit to the associate graduate in terms of additional income beyond

that of a high school graduate is shown in table ES5. These incremental income gains are

calculated after the student pays income taxes on gross earnings differences. The income gains

minus costs paid by the student, including lost earnings while studying, are about $138,000 for

each additional graduate in the comparison group, and about $146,000 for each additional

graduate in ASAP. The benefit to cost ratio for the associate recipient is 7.6 for each additional

graduate in the comparison group and 12.2 for each additional ASAP graduate. Another way of

stating the gains to the student beyond the costs paid (including foregone earnings for three

years) is that the income advantage of an associate degree beyond high school completion is the

equivalent of being given a certificate of deposit of about $140,000 net of taxes. This provides a

powerful incentive for students to undertake an associate degree at CUNY.

Table ES5: Net Benefits for the Student: Total Student Costs versus Benefits

After-tax Income

Benefits per

Degree (Student)

Total Cost per

Degree (Student)

Benefits minus

Costs (Net

Benefits)

(Student)

Benefit/Cost

Ratio

(Student)

Fall 2006

Comparison

Group

$158,742

$20,996

$137,746

7.6

Fall 2007

ASAP

Group

$158,742

$13,062

$145,680

12.2

In constant 2010 dollars.

9

AHighlyProductiveInvestment

From the comparison of benefits over a lifetime we can conclude that, for both taxpayer

and students, the benefits far exceed the investment costs. For each dollar of investment in

ASAP by taxpayers, the return was between three and four dollars. For each dollar of investment

by students, the return was much more, even when including student foregone earnings as the

major component of student costs. Using available data on which public constituencies receive

the benefits—federal, New York State, and New York City governments, we believe that all

constituencies receive benefits that exceed their cost contributions to the investment.

From a policy perspective, the full magnitude of the returns to the taxpayer must take

account of the superior effectiveness of ASAP in comparison with the conventional program.

When converted into overall benefits generated by the 1,000 enrollees, the considerably higher

productivity of ASAP in producing associate degrees would provide fiscal benefits to the

taxpayers of $46 million dollars beyond those of investing an approximately equal amount in the

conventional degree program.

Not only is ASAP less costly per additional graduate and twice as effective in the

production of associate degrees, but from the perspective of both taxpayer and student, the

benefits generated by ASAP represent a very productive public investment with a high monetary

return. Needless to say, this powerful public investment is buttressed further by the other

substantial educational contributions and success that cannot be assessed in monetary terms.

10

INTRODUCTION

In 2009 more than 7.5 million students were attending community colleges in the U.S.

(Bureau of the Census, U.S. Department of Commerce 2012). These institutions provide

opportunities for entry into higher education because of their geographic accessibility,

adaptability to student and employer educational needs, transfer route to four-year institutions,

and flexibility in scheduling and composition of courses. The reality, however, is that relatively

few students complete the 60-credit course of study to obtain the associate degree. According to

the U.S. Department of Education, only about 22 percent of students who enroll in community

colleges complete an associate degree three years later (Snider & Dillow 2011) and completion

rates are even lower in urban institutions.

3

In recognition of this challenge, the City University of New York (CUNY) established a

comprehensive program to assist students to complete their associate degrees with support from

the New York City Center for Economic Opportunity (CEO). This program became known as

Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) and is designed to increase dramatically the

number of students who complete an associate degree in a timely manner (Linderman &

Kolenovic 2012).

The goal of ASAP is to graduate at least “…50 percent of students within three years

through provision of comprehensive support services and financial resources that remove

barriers to full-time study, build student resiliency, and support degree completion” (Linderman

& Kolenovic 2012: 9). When ASAP began in 2007, the three-year CUNY community college

graduation rate was 24 percent for fully skills proficient students, based on CUNY analysis of

student-level data from the CUNY Institutional Research Database (IRDB),

4

and 13 percent for

all first-time full-time community college students who entered in fall 2004 regardless of skills

proficiency (CUNY Office of Institutional Research and Assessment, 2012).

ASAP was established at CUNY’s six community colleges:

5

Borough of Manhattan

Community College (BMCC), Bronx, Hostos, Kingsborough, LaGuardia, and Queensborough,

and uses a common and comprehensive design to overcome the obstacles to timely degree

completion. To counter these obstacles, the program enlists a variety of interconnected supports

(Linderman & Kolenovic 2012:10-11).

1. Financial Incentives: Any gap between a student’s financial aid award and tuition and

fees is waived, and all students receive free monthly transit Metrocards and free use of

textbooks.

3

CUNY Office of Institutional Research and Assessment (OIRA) analysis of data from

Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) reveals that nationally only 16 percent of urban

community college students graduate within three years.

4

The CUNY IRDB is the official source for all CUNY student-level data and is maintained by the Office of

Institutional Research and Assessment (OIRA).

5

CUNY opened a seventh community college, the New Community College (NCC) in fall 2012. NCC incorporates

many elements of ASAP into its design.

11

2. Consolidated Full-time Schedule: Classes are clustered into a consolidated schedule

(either morning or afternoon) to help balance school, work, and domestic responsibilities,

and students are required to take at least 12 units each semester.

3. Cohort Design and Faculty Support: Students are grouped in cohorts with ASAP students

by major; in their first year, they take several “blocked” classes with fellow ASAP

students that are capped at 25 students.

4. Regular Advisement: ASAP students meet with advisors monthly for provision of

academic, social, and interpersonal support. Students also participate in a weekly seminar

for two semesters.

5. Career Preparation: ASAP career and employment specialists meet with students for

career assessment, discussion of job skill requirements, career planning, and interview

preparation. They also support students with any immediate job placement needs.

6. Extra Academic Assistance: Tutoring is provided for struggling students. These services

are mandatory for students with outstanding developmental needs, those who have

experienced course failure, or those identified as struggling by faculty members through

referral to ASAP advisors.

Careful assessment of ASAP has provided evidence of its early promise with over half of

its initial cohort of 1,132 students who started community college in the fall of 2007 having

earned an associate degree three years later, in comparison with only about a quarter of a

matched comparison group of students who did not benefit from inclusion in ASAP (Linderman

& Kolenovic 2012). The second ASAP cohort admitted in 2009 also realized a three-year

graduation rate of 55 percent vs. 23 percent for a comparison group of similar students

(Linderman, 2012). These evaluations were accomplished by matching ASAP students with a

statistically similar group in terms of demographic characteristics, academic major, and

educational preparedness. Other evaluations are also underway using different methodologies—

for example, an experimental study using random assignment to ASAP, being led by MDRC.

6

ASAP has been shown to more than double the number of graduates in a three-year

comparison with similar students who did not benefit from ASAP services. Although the

program is more effective than the conventional community college pathways, the question

arises as to whether it is more cost effective. Implementing ASAP requires additional costs to

provide the extra services outlined above. In a previous cost-effectiveness study, we asked

whether the larger number of graduates compensate for the additional resource costs (Levin &

Garcia, 2012).

To undertake the cost-effectiveness analysis, we compared the institutional costs per

associate degree completion of students in ASAP with that of a comparison group of similar

students who did not participate in ASAP. This comparison revealed that the cost per three-year

6

A preliminary report from MDRC on the ASAP random assignment study can be found at:

http://www.mdrc.org/node/13229#featured_content

12

graduate with an associate degree was actually less for ASAP than for the comparison group.

Although the program costs were greater, the increase in the number of three-year graduates was

so substantial that the cost per completed degree for ASAP students was about $6,500 less than

for the comparison group. This difference suggests that not only is ASAP more cost-effective

than the conventional approach, but that CUNY could save about $6.5 million in producing

another 1,000 graduates through ASAP.

ReturnsonInvestment:ABenefit‐CostAnalysis

Cost-effectiveness analyses address the relative costs among alternatives for achieving

particular goals. In the case of increasing the numbers of three-year graduates in the community

colleges of CUNY, this evaluation has shown that ASAP can double the number of graduates in

a three-year period and do it at less cost per graduate than the conventional program without

ASAP. Cost-effectiveness comparisons enable us to choose the most efficient approaches for

achieving objectives, but they do not evaluate the returns to investing in a program like ASAP.

They provide information that enables us to choose those approaches that accomplish a particular

goal with the least resources.

In contrast, benefit-cost analyses enable us to ascertain whether a particular alternative is

“worth it” by comparing the costs in monetary terms with the value of the benefits in monetary

terms. In the case of improving educational success, there are obvious benefits to the student in

terms of better employment and job opportunities and improved options for further education, as

well as better health, greater knowledge, and the ability to learn new things. But there are also

benefits to the taxpayers who pay much of the cost of investment in education. By increasing the

numbers and quality of educated persons in society, the society gains from higher economic

productivity and income, as well as greater technological advance and inventive activity. It also

experiences fiscal benefits in higher tax revenues and lower demand for and costs for spending

on public health, criminal justice, and public assistance (Belfield & Levin, 2007a).

This report compares the benefits and costs of additional associate degrees produced by

ASAP to ascertain if the benefits exceed the costs and the magnitude of the differences.

Although some reference will be made to the individual costs and benefits, the focus will be

primarily on the fiscal costs and benefits to the taxpayer. That is, we will address whether

taxpayer investments in producing additional associate degrees at CUNY community colleges

through ASAP will produce taxpayer benefits that are equivalent or greater.

The basic method for making such benefit-cost calculations has been used in education

since the early sixties when economists refined the method of analysis for investment in human

capital (Becker 1964). Economists found that investments in education showed rates of return

that were comparable or greater than those found for investments in physical capital-- that is,

productive facilities and equipment, the traditional focus of investment. Although this literature

referred largely to the “profitability” of individuals investing in further education, it extended to

societal investments and the investment benefits to society of more education.

13

The first attempt to apply these methods to a benefit-cost analysis of taxpayer investment

was conducted in 1972 with an analysis of the costs and benefits of reducing high school

dropouts (Levin 1972). This study compared the costs of reducing dropouts with the benefits of

increased income and tax revenues as well as reduced costs of public assistance, crime, and

public health. The limited informational resources and statistical methods available forty years

ago restricted the comprehensiveness and precision of benefit-cost estimates, but even with

conservative assumptions it appeared that the benefits to the taxpayer of reducing high school

dropouts exceeded the costs by at least two to one.

A more refined analysis was applied to an experimental study of a specific investment in

early childhood education. Children at ages three and four from poor families were randomly

assigned to an experimental group that received a quality, pre-school program or a control group

that did not. At age 19 it was found that the pre-school recipients had greater educational

success, lower crime rates, and greater employment prospects than the comparison group that

had not been enrolled in the pre-school. A calculation of benefits to the taxpayer showed that for

every dollar of investment cost, the benefits exceeded six dollars (Barnett 1985). The follow-up

studies of the two groups at ages 27 and 40 confirmed even higher benefits (Belfield, Nores,

Barnett & Schweinhart 2005).

Dramatic improvements in data sources and social science modeling of benefits have

generated studies of benefits and costs of specific educational programs to reduce high school

dropouts (Belfield & Levin 2007b). Five studies were selected from experimental and quasi-

experimental evaluations that showed evidence of increasing graduation rates. The public costs

of these programs were compared with the public benefits in terms of higher tax revenues and

reductions in public costs of crime, health, and public assistance. All five programs showed

benefits in excess of costs, with the median program among the five showing that fiscal benefits

would exceed costs by $127,000 for each additional graduate over a lifetime when valued at age

20 (Levin, Belfield, Muennig, & Rouse 2007; Levin & Belfield 2007). Similar studies were

carried out for states with similar results (e.g. Belfield & Levin 2007b).

Methods

The general approach used for measuring the benefits of education is first to identify the

benefit categories and the evidence behind them. Then it is necessary to place values on

benefits. In the case of completion of an associate degree the benefits are associated with greater

adult success of the individual relative to what the individual would have experienced if he or

she had terminated education at the end of high school. What we do know is that individuals

with more education obtain higher earnings and pay greater taxes (Rouse 2007); experience

better health and lower likelihood of drawing on government health services (Muennig 2007);

are less likely to engage in crime and to enter the criminal justice system (Moretti 2007); and are

less likely to require public assistance (Waldfogel, Garfinkel, & Kelly, 2007). All of these better

outcomes provide benefits to society and the taxpayer by increasing public revenues and

14

reducing the costs of public services. It is this increase in public income and reduction in public

costs that constitute many of the public benefits of additional educational attainment.

In the case of ASAP it would be expected that the additional associate degrees would

produce benefits for the ASAP students as well as for the taxpayer. That is, more associate

degrees translate into greater employment and higher income and tax revenues as well as lower

costs for public health, crime, and public assistance. The value of these public benefits can be

compared with the public costs to ascertain the return on taxpayer investment in ASAP.

ModelingRelationships

Of course, in each of these domains we want to estimate benefits independently of other

possible influences that might be associated with more educated individuals. For example, it is

well known that persons who undertake more education have family advantages and may have

greater educational ability as well. This means that at least some of the additional income and

other benefits of education might be due to associated advantages of the more educated, but are

not uniquely education-induced. Economists have long been concerned with this potential

upward bias in estimating the benefits of education, and have tested a range of methods to try to

separate out the unique effects of education on adult benefits.

These methods have included statistical adjustments for family socioeconomic status and

for an individual’s test performance as well as the use of more sophisticated analytical models.

The latter (see Rouse, 2007) include studies of identical twins with different amounts of

education (but the same families and genes); studies of education and earnings of fraternal twins,

siblings, and father-son pairings. They also use natural experiments to isolate the unique effects

of education, where changes in laws impose more education on a group of students such as

arbitrary increases in compulsory education. The findings from all of these methods suggest that

the observed differences in earnings by educational level are not biased upwards because they

are roughly offset by measurement errors in educational attainment that provide a downward bias

(Rouse 2007). As much as possible we have tried to use estimates of effects based upon causal

models from the academic literature rather than accepting mere correlation.

DataandMeasurement

To a very high degree, CUNY’s community college graduates remain in the New York

metropolitan area and in New York City.

7

This creates an advantage to the City in capturing the

benefits from more education, but a challenge for data collection by researchers. State and

national studies on the consequences of additional education have access to considerable data on

these larger entities. Both independent studies and government studies by the Department of

Justice or the Department of Health and Human Services provide systematic information for the

nation that link education to crime and to health respectively. But, systematic studies at local

7

This is discussed in the later section on community college graduates’ mobility (see page 47).

15

levels are rare to non-existent. The exception is that of the relation between education and

income and its yield of government tax revenues for which data are available from the U.S.

Department of Commerce, and, particularly, the Bureau of the Census. In what follows, we will

be drawing upon the best data sources available on each topic to predict the benefits to the

taxpayer of CUNY ASAP’s success in substantially increasing the timely completion of

associate degrees.

PresentValue

Present Values at Age 23

Both benefits and costs will be based upon comparing three-year associate degree

recipients with those of high school completers who have not entered post-secondary education.

8

Data for partial completers of community college degrees are not available. Costs and benefits

will be stated in terms of present values (PV) in 2010, which is the three-year graduation mark

for students in the original ASAP cohort and the cohort that served as the basis of our study. It is

important to explain PV and why it is used. If costs of additional education and its benefits were

derived in a single year, they could be readily compared. But the costs and benefits of

educational investment occur over different periods of time. For example, the three years of

community college investment to obtain an associate degree necessitate a financial obligation

prior to graduation and produce benefits following graduation. Benefits extend from completion

of study over an entire lifetime. If the typical graduate is 23 years old

9

, we are concerned with

the cost of community college during the previous three years to age 23. Subsequently, the

benefits of the additional education will typically be yielded between the ages of 23-65, a period

of more than 40 years. All of the investment is concentrated early and “up-front,” but the benefits

are delayed and distributed over the next four decades after completion of the associate degree.

We use PV because it allows us to account for a stream of benefits and costs in one simple

figure.

The calculation of PV assumes that benefits received at present have more value than

those that are received in the future. The normal way of valuing future benefits is to use a

discount rate, reduce them by a rate of interest, to make them comparable to benefits received at

present. For example, if you wanted to have $10,000 in 40 years in a lump sum, you would need

to invest only about $2,500 today with a discount or interest rate of 3.5 percent. Another way of

stating this is that $2,500 today is worth $10,000, 40 years from now. Present value simply takes

account of the different time patterns of receipt and disbursement and puts them in comparable

8

We have made all comparisons of benefits and costs between high school graduates and associate degree graduates.

We also attempted to undertake analyses comparing partial completers with associate degree recipients.

Unfortunately, the data that exist for those with “some college” encompass a wide range of education from those

who have taken a single course to those who have completed almost an entire bachelor’s degree. Thus, they cannot

be used to represent “partial completers” studying for the associate degree.

9

The average age of a three year graduate would be 23 for ASAP based on a mean starting age of 20 (see Linderman

and Kolenovic 2012 pg. 17).

16

terms so that they can be compared directly. By expressing benefits and costs in present values at

age 23 in 2010, we will be able to use a comparable yardstick that adjusts for the very different

time patterns in which the costs and benefits are incurred or received for an associate degree

relative to high school completion. The present value of the costs can be subtracted from the

present value of the benefits at a specific time to get “net present value,” the net benefits that are

produced by the investment.

LaborMarkets

Since we will be estimating the income and tax revenue gains of associate graduates as

one of the major benefits to degree recipients and the taxpayer, an obvious concern is the impact

of more graduates on the labor market. If we add substantially to the supply of associate

degrees, won’t we reduce the returns to each one? This would certainly be a concern if the

demand for associate degrees held constant while the supply increased significantly through the

success of ASAP. In actuality, the overall trend in U.S. labor markets is in exactly the opposite

direction, where the relative economic value of post-secondary education is rising in comparison

with that of high school graduates. Empirical studies confirm that even with massive increases

in community college graduates, the economic returns have not declined (Marcotte, Bailey,

Borkowski, & Kienzl 2005). The general explanation is that changes in technology and work

organization and the decline of manufacturing have increased the demand for post-secondary

educational skills relative to lower levels of education. If anything, the use of existing data on

earnings differences by education may understate the future benefits to the individual, taxpayer,

and society of additional education.

COSTSOFTHECUNYASSOCIATEDEGREE

As a first task, we establish the costs of producing a CUNY associate degree for both the

comparison students representing the regular program and for the ASAP students to contrast

costs with the later presentation of benefits that the degree produces for the individual, the

taxpayer, and society. There are several ways that costs can be presented. As noted earlier, we

could list the cost for each year incurred and the benefits for each year received, but this

approach would compare amounts over very different time patterns which are not comparable.

As described above, the standard approach is to state both costs and benefits as “present” values

(PV) at a particular age or time, which enables a comparison that adjusts for the amount and time

distribution of each. We will use age 23 as a typical age of completion of degree and estimate

both the present value of the costs at that age and the value of benefits received when discounted

to age 23.

Levin and Garcia (2012) estimated the costs of producing additional associate degrees

within a three-year period for both the regular programs of CUNY and with the added support

from ASAP. Although ASAP adds additional costs, it also increases the number of degree

completions. The basic method of establishing costs was to first calculate for the ASAP group

17

the costs of their aggregate, full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollments over three years.

10

This was

compared with the overall costs of full-time equivalent students (FTE) of the comparison group

that had not received ASAP services. These costs were then divided by the respective numbers

of associate degrees produced in each group over the three-year period to determine a cost per

graduate. Even with the additional spending for ASAP services, the cost per graduate was less

than for the comparison group because of the much higher yield of graduates, about 55 percent

for ASAP and 25 percent for the comparison group.

Table 1 shows the total institutional cost per graduate expressed as present value (PV) in

2010 at age 23.

11

Although the cost per ASAP student is higher than for the traditional student

because of the extra services, the institutional cost for each graduate is less for students in ASAP

because of the considerably higher graduation rates for ASAP. How institutional costs are

financed will be addressed in later sections, as well as student costs.

Table 1: Total Institutional Cost per Graduate

Total Fall 2006

Comparison Group

Total Fall 2007

ASAP Group

Total Institutional Cost per Graduate

$65,884

$59,302

Notes: The total institutional cost per graduate is the capitalized average cost per graduate at age 23, in 2010 dollars

(see Table 5, Levin & Garcia, 2012).

The overall institutional cost incurred by CUNY for each associate degree (expressed in

terms of present value at age 23) is about $59,000 for the ASAP students and almost $66,000 for

the comparison group. These amounts are slightly more than the totals in Levin and Garcia

(2012) because an interest rate is used to calculate their present value to age 23, assuming that

the typical graduate starts at about age 20 and finishes at age 23. These institutional costs do

include some student costs in terms of tuition and fees. Students also may forego earnings during

the period of study and pay for materials and other costs related to their education. We will focus

the following section of analysis primarily on the cost and returns of the ASAP investment for

the taxpayer. Essentially we will be comparing the institutional costs of conventional and ASAP

students with the benefits generated for taxpayers. This is a conservative approach to the

benefit-cost ratio since not all of the institutional costs are paid by the taxpayer, but a small

portion is paid by the student. Thus, by assuming that all of the institutional costs are paid by the

taxpayer, we will be understating the benefit-cost ratio because we will be assuming higher costs

than the taxpayer actually pays.

10

Full-time equivalent students (FTE) are a commonly used measure for enrollments because instead of just

counting students, they adjust for the number of credits of study undertaken by students so that part-time students

are not given the same enrollment weights as full-time students.

11

The present value represents the cumulative cost expressed in 2010 prices over the three years, presented as the

present value of the investment at age 23. Present value cumulates the investment at an interest rate of 3.5 percent to

get an overall value which can ultimately be compared with the discounted value of the benefits generated when the

costs of the investment and the benefits are compared at age 23.

18

BENEFITSOFASAP

It is important to note that although the costs differ between the two programs for

producing an associate degree, the average benefits for a CUNY associate degree are assumed to

be similar for the two groups since they have relatively similar educational requirements. The

major difference educationally is that a far higher proportion of the non-ASAP students who start

their programs reduce their participation sharply or drop-out, resulting in lower completion rates

for the associate degree (also lower transfer to baccalaureate institutions (Linderman &

Kolenovic 2012)). We will limit this analysis to the benefits of higher associate degree

completion because we lack information on the eventual educational attainments of transfers.

From a cost perspective, the big advantage of ASAP is that even with added program

costs per student, the cost per graduate is lower than the conventional program because the yield

in terms of graduates is doubled. Thus, when we calculate the benefits of the associate degree to

compare with the costs, we will assume that both ASAP and non-ASAP graduates generate the

same benefits per degree, but the costs will be slightly different. We will also show that the

higher yield of ASAP means that the aggregate benefits for any initial group of ASAP enrollees

will exceed considerably the aggregate benefits for a similar number of enrollees who are not

recipients of ASAP services.

As we noted earlier, there are many benefits of higher education that are identified in the

literature, but not all can be measured and given monetary values. McMahon (2009) has

provided one of the most comprehensive presentations and discussion of these benefits, but only

a portion of these defy monetary quantification. The incomplete assessment of benefits gives a

conservative estimate of the payoffs to the investment in ASAP because it includes only those

that can be assessed monetarily, while costs are more readily defined and measured. Specific

benefits of increased associate degree attainment that can be assessed sufficiently to determine

their monetary values include:

1. The additional income reflecting higher productivity and trainability of an associate

degree completer relative to a high school graduate, reflecting benefits to the student and

to society.

2. The higher tax revenues derived from the additional income, reflecting fiscal benefits to

the taxpayer.

3. The reduced costs of public services for crime, public health, and public assistance,

reflecting fiscal benefits to the taxpayer.

4. Overall gains in productivity of other workers created by the presence of a more educated

workforce.

In the following section we will focus on estimating the return on investment to the

taxpayer in terms of higher taxes generated by the increase in associate degrees and the reduction

in cost of public services associated with the additional education. These are the fiscal returns to

19

taxpayer investment through investment in ASAP. In the final section we will consider other

benefits to both individuals and society.

Education,Income,andTaxRevenues

One of the most powerful and consistent findings in the economics of education is the

measurable impact of additional education in producing additional economic opportunity for

both the individual worker and society. Workers with more education are valued more highly in

the workplace because they tend to be more proficient at jobs, benefit more from additional

training, and make better and more productive decisions in the allocation of resources, including

the use of their own time. Out of their higher income they pay greater taxes, which represent the

source of the public share of investment in their education.

In this section we compare the income and tax contributions of individuals with an

associate degree such as those who graduate within three years from ASAP with those who

obtained high school completion or its equivalent.

12

We calculate the benefits for the individuals

and the taxpayer along the following dimensions: earnings; income tax contributions, property

taxes, sales taxes, and local income taxes. In the next section we will provide estimates of the

reductions in public health expenditures, welfare support and public assistance, and criminal

justice associated with associate degree completion. The procedure to compute the PV of the

modeled relationships between educational attainment and these outcomes is explained in the

earlier section on “Present Value.”

IncomeGains

The relationship between education and earnings has been largely documented in the

empirical research (Angrist & Krueger, 1991 and 1999; Griliches, 1979; Ashenfelter & Rouse,

1998; Card, 1999; and Rouse, 2007). On average, individuals with higher educational levels have

higher earnings. They are also more likely to be employed. Figure 1 and Table 2 show these

associations between education and labor market outcomes for both males and females.

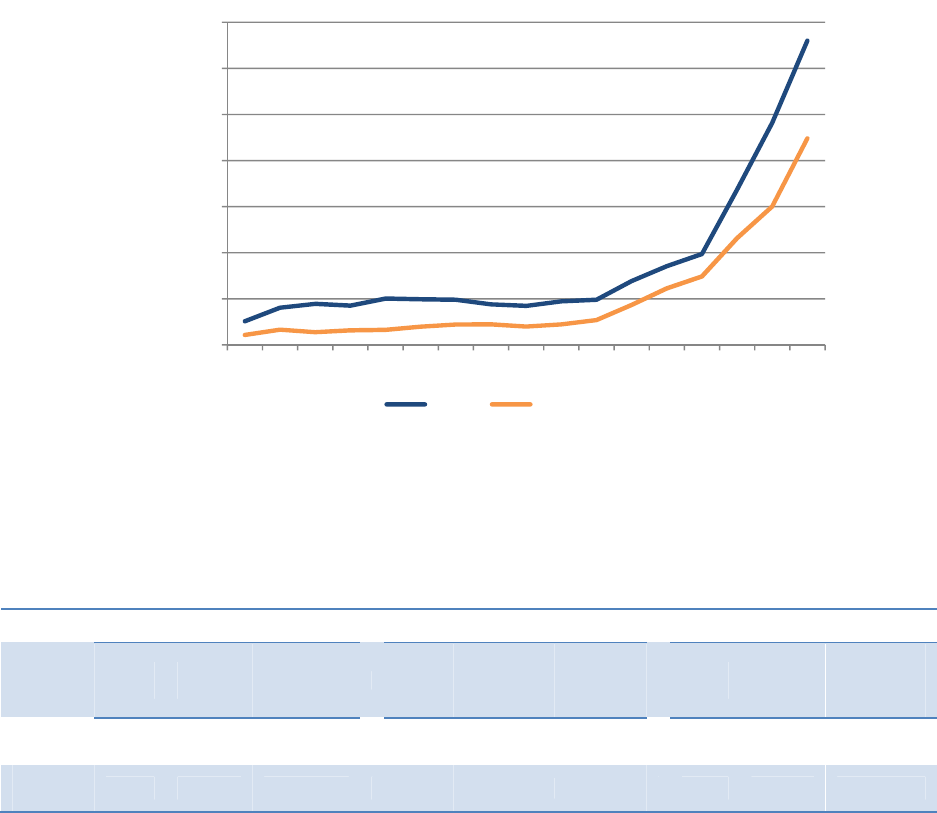

Figure 1 shows the average earnings

13

by years of schooling and gender for individuals in

New York City, demonstrating the familiar finding that more years of education are associated

12

Educational attainment is defined, according to the American Community Survey (ACS) and Census information

as:

i) High school graduate or GED; Regular high school diploma; GED or alternative credential (the

acronym “HS” is used in tables and figures hereafter).

ii) Associate degree –type not specified, occupational program, academic program.

The classification is slightly different under MEPS-2008, utilized for the estimates of the health expenditures

savings. A few data sources show income for those with “some college”. Unfortunately the “some college” category

is highly ambiguous and includes a wide range of educational attainments from a single post-secondary course to

many years of study that did not culminate in a degree (the acronym “AA” is used in some figures hereafter).

13

We will refer to earnings and income interchangeably. They are not identical. Earnings are derived from wages

and salaries; income includes not only wages and salary, but also rents, dividends, and interest from property, etc.

However, for high school and associate degree populations, the proportion of income from earnings is usually 95

percent or greater.

20

with higher average earnings. The relationship between education and income is particularly

pronounced between 12 years of schooling and 14 years of schooling, the approximate difference

between high school completers and associate degree recipients. Table 2 shows the labor market

status of individuals by their educational attainment. The rates are shown separately by gender.

At first glance it appears that employment and unemployment rates of high school completers

and associate degree completers are about the same, but this comparison is misleading because it

does not take account of the differences in labor force participation of the two groups. For

associate degree holders in the 23-65 year old population, the associate degree recipients are 10

percentage points more likely to be in the labor force. This means that even with the same

unemployment rates, a much higher proportion of the associate degree holders are employed, a

partial explanation for their higher incomes.

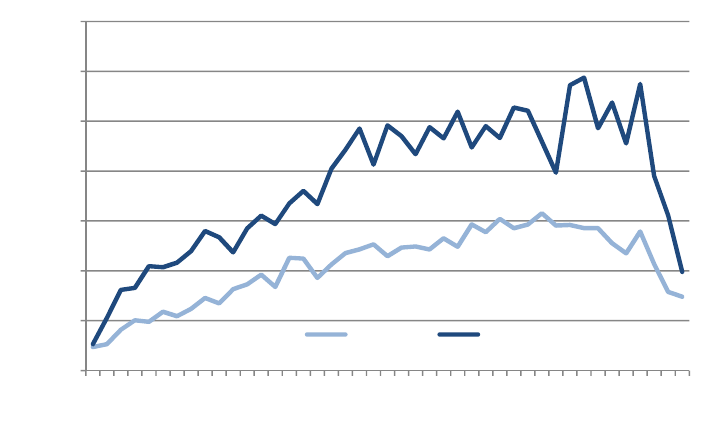

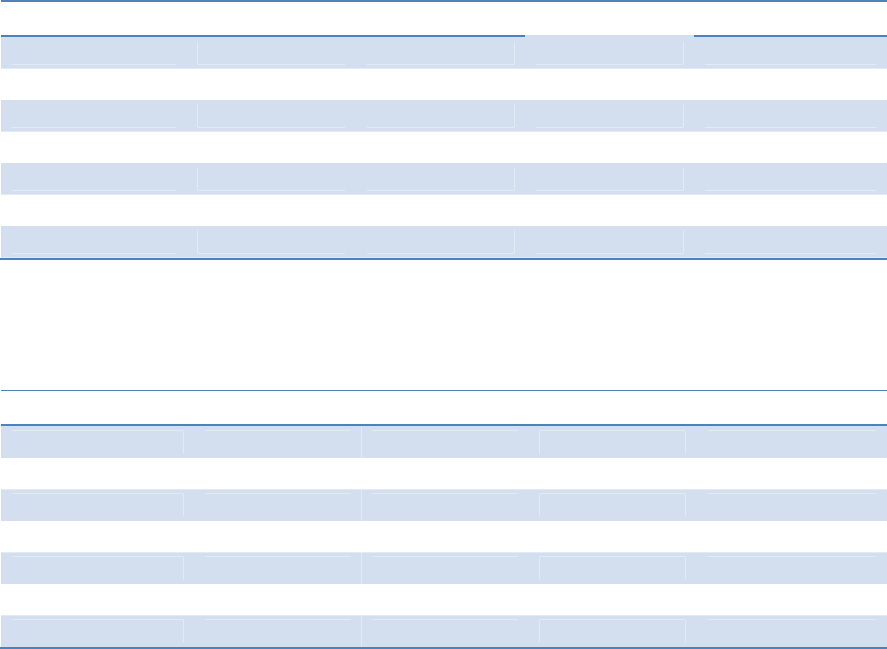

Figure 1: Average Earnings and Years of Schooling, 2008-10

Years of Schooling (HS = 12; Associate= 14)

Note: American Community Survey, 2008-2010, Individuals in New York City, ages 23-65 (population

weighted means). In constant 2010 dollars.

Table 2: Employment and Unemployment Rates, and Economically Active Population

(% in the Labor Force) by Educational Attainment, 2010

Males Females Total

Employ.

Rate

Unemploy.

Rate

Economically

Active Pop

(% in labor

force)

Employ.

Rate

Unemploy.

Rate

Economically

Active Pop

(% in labor

force)

Employ.

Rate

Unemploy.

Rate

Economically

Active Pop

(% in labor

force)

High

School

88.2% 11.8% 80.0%

90.1% 9.9% 62.6%

89.0% 11.0% 71.2%

Associate

Degree

89.3% 10.7% 83.9%

90.1% 9.9% 78.9%

89.7% 10.3% 81.0%

Note: American Community Survey, 2010, Individuals in New York City, ages 23-65 (population weighted means).

$0

$20,000

$40,000

$60,000

$80,000

$100,000

$120,000

$140,000

1234567891011121314171819

Males Females

21

In order to calculate the average earnings differentials between individuals with high

school completion versus an associate degree in New York City, we exploit the American

Community Survey (ACS, hereafter), between 2008 and 2010. We use population weighted

means for the inflation-adjusted wages and salaries of individuals in New York City, between 23

and 65 years old, and assume that productivity grows at a constant rate of 1.5 percent per year

(see Rouse, 2007, page 114). The values are expressed in constant dollars by adjusting all values

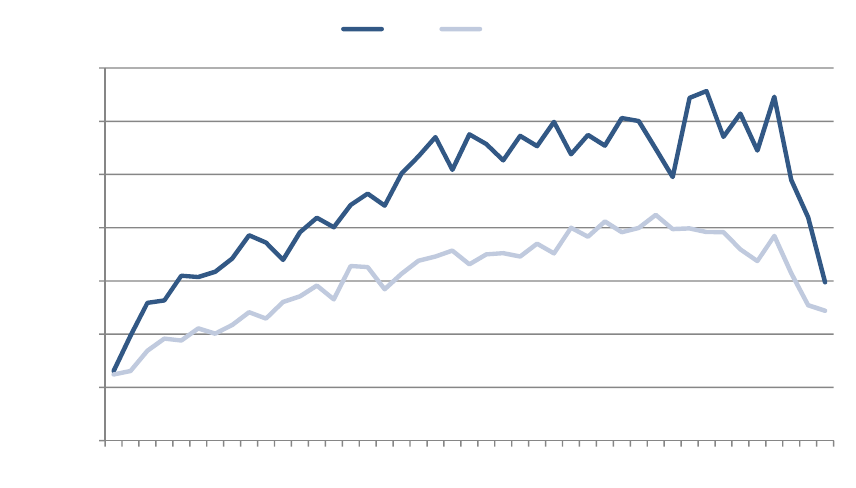

to the 2010 price level. Figure 2 shows the age-earnings relationships for the subgroup

populations in New York City. We note that average earnings are higher for individuals with an

associate degree than for those who have limited their education to high school completion. The

earnings-gap widens shortly after age 23, and continues over the years.

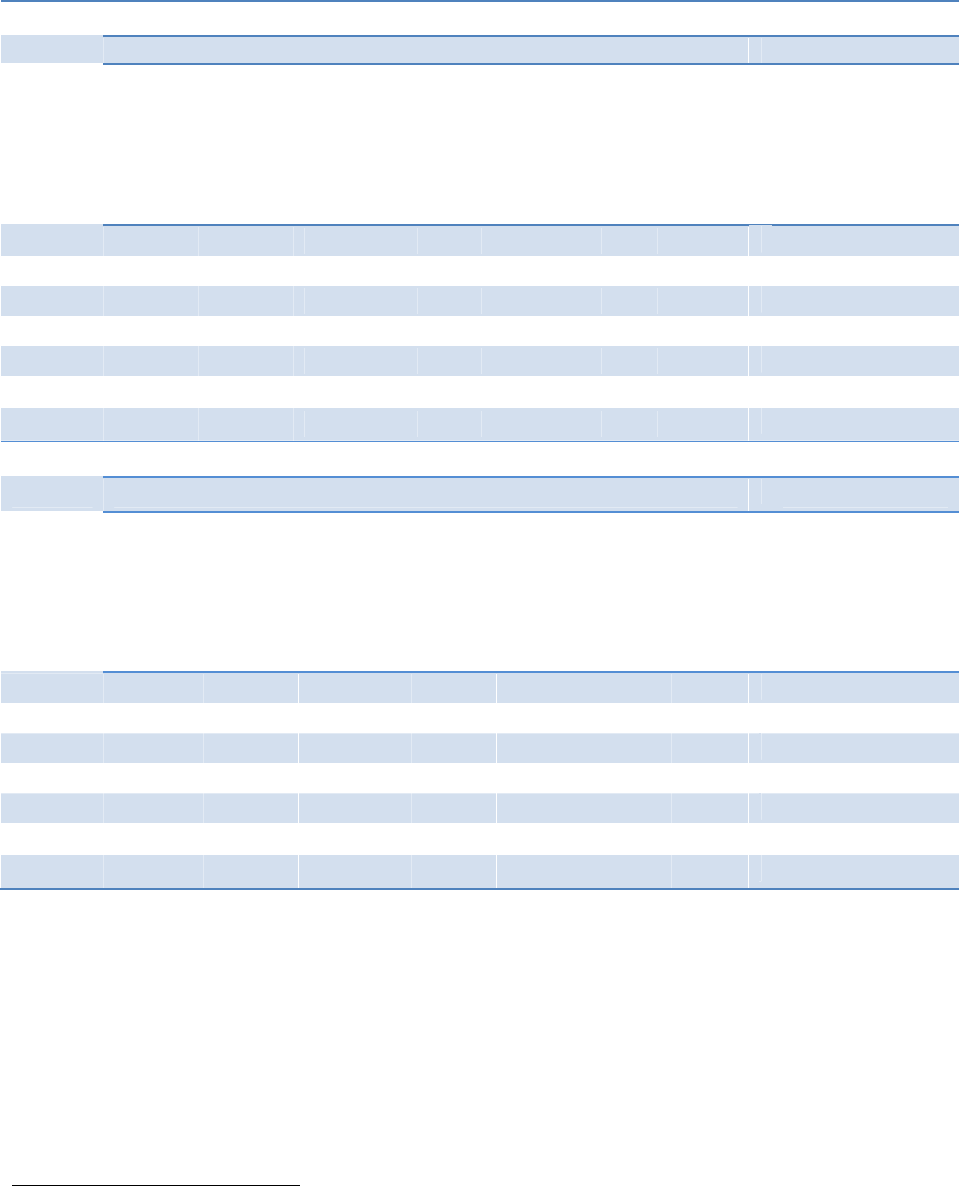

Figure 2: Age-Earnings Profiles by Educational Attainment, 2008-10

Source: ACS, 2008-2010

Note: Individuals in New York City, ages 23-65, population weighted means, constant 2010 dollars, all individuals

in the labor force (i.e., individuals with zero and positive earnings, employed, unemployed, out of the labor

force/inactive). Productivity increases yearly by 1.5%.

In order to compare the private income benefits for the student, we wish to compare the

present value of income from age 23 to age 65 for those with the associate degree and those with

a high school diploma or equivalency degree. We assume that productivity growth equals 1.5

percent increase per year. The discount rate is 3.5 percent (Moore, Boardman, Vining, Weimer &

Greenberg, 2004).

$-

$10,000

$20,000

$30,000

$40,000

$50,000

$60,000

$70,000

23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 47 49 51 53 55 57 59 61 63 65

AA HS

22

Table 3: Lifetime Earnings by Educational Attainment. Breakdown by Gender, and

Ethnicity (Present Value at Age 23 at 3.5 Percent Discount Rate), 2008-10

High School Associate

Associate minus HS

Total

1

640,330 964,472

324,142

Male 790,064 1,128,983

338,919

Female 485,903 848,132

362,229

White 792,455 1,128,714

336,260

Black 616,739 926,892

310,153

Hispanic 566,767 869,654

302,887

Other 532,962 857,746

324,784

Source: Authors’ calculations based on ACS 2008-2010. Productivity increase per year: 1.5 percent. In constant

2010 dollars.

1

Total represents an average of graduates representing the gender and ethnic distribution of New York City.

Table 3 shows the present value of lifetime earnings for high school credential and

associate degree recipients overall as well as by gender and race. The total or average for the

overall group at the top of the table is an average based upon the overall composition of the New

York City population. We assign this outcome to CUNY graduates, on the premise that CUNY

community college enrollments are demographically representative of the population in New

York City. The advantage in present value of lifetime earnings for the associate recipients

varies from about $310 thousand to about $362 thousand, depending upon the group. This is a

substantial lifetime premium for an associate degree. As a reminder, the present value

calculation may be thought of as the value of a certificate of deposit (CD) with a 3.5 percent

interest rate that is given to the student on completion of their associate degree. Since degree

requirements are similar for both ASAP and non-ASAP graduates, we assume that the income

benefits will be similar too.

AdditionalTaxRevenuesfromStateandFederalIncomeTax

The higher income

14

for individuals with an associate degree is an important source of

additional fiscal gains for the taxpayers (Rouse 2007). In order to estimate the expected state and

federal taxes for social security and Medicare (FICA) taxes paid by individuals with earnings, we

use the NBER-Taxsim, version 9.0

15

that was designed for this purpose. To provide information

that is representative of the potential benefits of the CUNY ASAP graduates, who are likely to

remain in the New York Metropolitan area, we use estimates based upon residents of New York

State who are single,

16

only have earnings from income, and have no itemized deductions. We

use the fiscal structure existing in 2010, and the consumer price index (CPI) adjusted to constant

14

Tax contributions are calculated on earnings, as a proxy for an individual’s total income. For the groups studied in

the report, earnings constitute more than 90 percent of income.

15

Available http://users.nber.org/~taxsim/taxsim-calc9

16

Rouse 2007 and Levin, Belfield, Muenning & Rouse (2007) used the same method. As a check, we estimated the

tax contributions from earnings for married people. The results for married people are shown in the Appendix. Total

taxes for married people were, on average, 15% lower than for single people.

23

2010 dollars. The tax base is also adjusted for a productivity increase in earnings of 1.5 percent

per year.

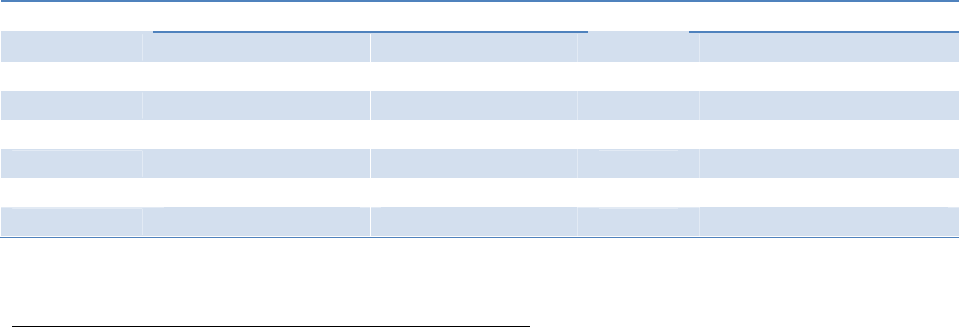

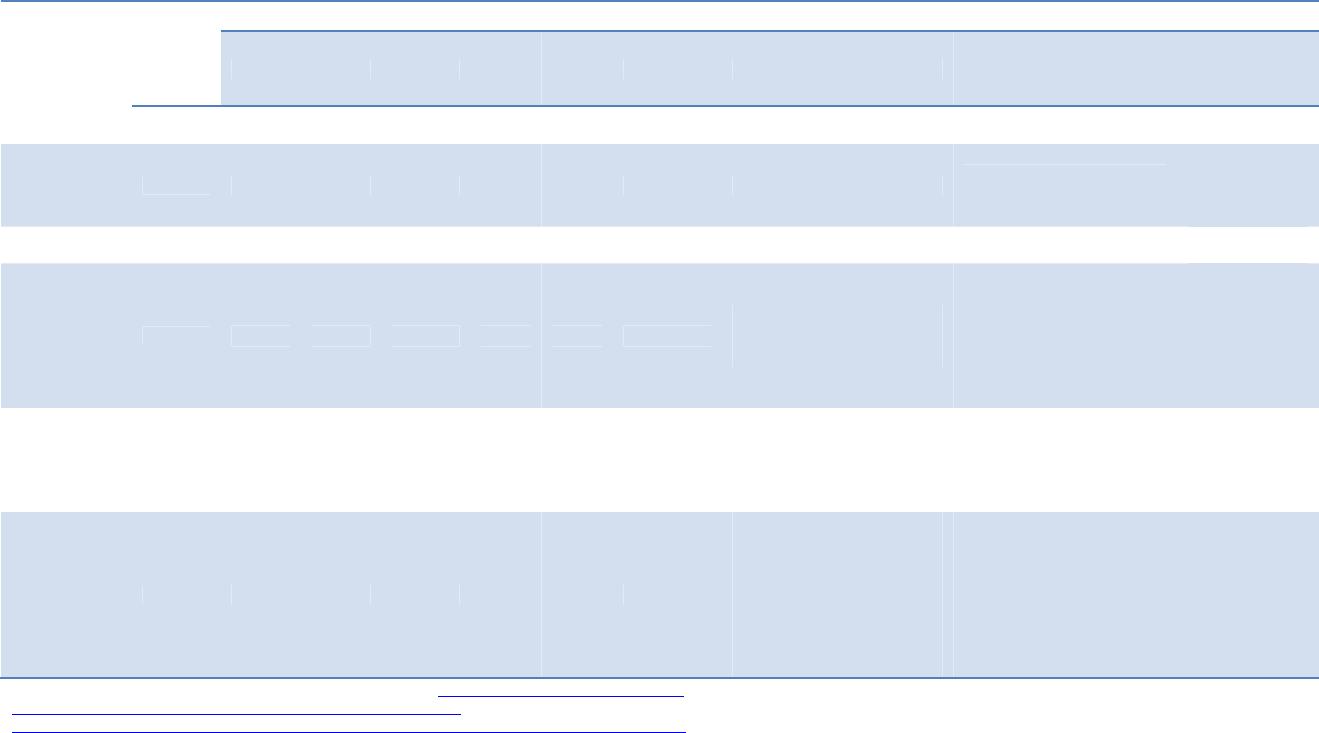

Figure 3 shows the average annual taxes on income by associate or high school

educational attainment. As with the lifetime patterns of income, the lifetime tax contributions

widen until near retirement. It is the difference between these two profiles that represents benefit

recovery to the taxpayer from additional tax revenues for each additional associate degree

recipient relative to the high school graduate.

Figure 3: Federal, State, and FICA Age-Income Tax Profiles by Educational Attainment,

2008-10

Age

Source: Calculations based on ACS 2008-2010 incomes and NBER-Taxsim, version 9.0, in constant 2010 dollars.

Table 4 summarizes the estimates of taxes paid by high school completers and associate

degree recipients. Present values at age 23 are calculated using a discount rate of 3.5 percent. All

amounts are expressed in 2010 constant dollars. Table 4 also provides the calculations by gender

and ethnicity.

The first three columns show the amount of federal, State and FICA taxes paid by the

individuals. On average, individuals with an associate degree are expected to contribute

$106,000 in federal taxes, $45,000 in state taxes, and about $148,000 in FICA taxes over their

life time (see bottom panel, columns 1, 2, and 3). In contrast, individuals who completed high

school pay about $46,000 in federal taxes, $24,000 in state taxes, and almost $98,000 in FICA

tax contributions over their life time (top panel, columns 1, 2, and 3).

$-

$4,000

$8,000

$12,000

$16,000

$20,000

$24,000

$28,000

23 26 29 32 35 38 41 44 47 50 53 56 59 62 65

HS AA

24

Table 4: Lifetime Earnings, City, Property and Sales Taxes by Educational Attainment.

Breakdown by Gender and Ethnicity (Present Value at Age 23 at 3.5 Percent Discount Rate)

By Type of Tax

Total

High School Completers

Federal

Income

Tax

Liability

after all

Credits

State

Income

Tax

Liability

after all

Credits

FICA

(OADSI

& HI,

Employee

&

Employer)

City

Income

Tax

(Net)

Property

Tax

NYC

Sales

Tax

NY

State

Sales

Tax

Total High School

Completers

Total

45,749 23,614 97,970 26,788 7,522 15,977 15,682

233,303

Male

70,413 33,627 120,880 33,052 9,281 19,712 19,349

306,313

Female

23,339 13,995 74,343 20,327 5,708 12,124 11,900

161,736

White

71,071 33,860 121,246 33,152 9,310 19,772 19,408

307,819

Black

42,506 22,149 94,361 25,801 7,245 15,388 15,104

222,554

Hispanic

34,734 18,670 86,715 23,710 6,658 14,141 13,880

198,509

Other

30,353 16,934 81,543 22,296 6,261 13,298 13,053

183,738

Associate Degree Recipients

Federal

Income

Tax

Liability

after all

Credits

State

Income

Tax

Liability

after all

Credits

FICA

(OADSI

& HI,

Employee

&

Employer)

City

Income

Tax

(Net)

Property

Tax

NYC

Sales

Tax

NY

State

Sales

Tax

Total Associate

Degree

Total

106,319 45,457 147,564 40,348 11,330 24,064 23,620

398,703

Male

143,330 56,775 172,734 47,230 13,263 28,169 27,649

489,150

Female

83,449 37,471 129,764 35,481 9,964 21,161 20,771

338,061

White

141,502 56,613 172,693 47,219 13,260 28,162 27,643

487,093

Black

99,773 42,877 141,815 38,776 10,889 23,126 22,700

379,955

Hispanic

86,956 39,053 133,057 36,381 10,216 21,698 21,298

348,659

Other

89,391 38,570 129,562 35,883 10,077 21,401 21,007

345,891

Source: earnings’ taxes calculated based on ACS 2008-2010 and NBER-Taxsim, version 9.0, in constant 2010

dollars. Productivity increase of income (the tax base) is 1.5 percent per year. City income, property, NYC Sales and

NY State taxes are calculated based on ACS 2005-2010

17

and City and State sources (see Table A1 in the Appendix

for details). Columns may not sum to total due to rounding.

17

In order to utilize the maximum amount of information about property and sales tax rates, available since 2005,

we utilize ACS between 2005 and 2010.

25

AdditionalTaxRevenuesfromCityIncome,PropertyandSalesTaxes

Based upon other studies, an amount of 5 percent of total income could be added to cover

property and sales taxes (see Levin, Belfield, Muennig & Rouse, 2007, p.24). This amount is

thought to be a conservative approximation,

18

given the characteristics of the taxes in the City

and State of New York. Using the information listed in Table A1 (in the Appendix), we calculate

the sales, property and other local taxes for individuals who reside in New York City. On

average, an associate degree recipient pays almost $100,000 in these taxes ($40,000 in City

income tax, $11,000 in property tax, and about $40,000 in sales taxes; bottom panel, columns 4

to 7), compared to almost $66,000 paid by the average person who graduated from high school

(the breakdown for this person is $27,000 in City income tax, $7,500 in property tax, and about

$32,000 in sales taxes top panel, columns 4 to 7). We should keep in mind that this is the present

discounted value of the higher taxes paid by associate degree recipients relative to high school

completers.

OverallTaxBurden

As shown in Table 4, individuals with an associate degree contribute, on average, almost

$398,700 in lifetime taxes (overall tax contributions from earnings, property and sales) over their

lifetime, present value at age 23. Individuals with a high school diploma or GED pay, on

average, about $233,000 in total tax contributions over their lifetimes. In viewing the benefits to

the taxpayer of an additional associate degree, we can compare the additional tax revenue

contributed by an associate degree recipient with that of a high school completer. Table 5 shows

the difference in the present value of lifetime aggregate taxes between the recipients of these

degrees, by gender and ethnicity. On average, a person with an associate degree contributes

$165,000 more in tax revenues than a person who completed high school. Although we will

address this issue later, note that the value of additional tax revenues alone from an associate

degree is about twice as large as the public investment required to fund the degree (that ratio is

even larger if we take into account that student tuition is part of the institutional cost). An

additional 1,000 associate graduates would generate about $165 million dollars of additional tax

revenue, measured in present value at age 23.

18

We assume total income equals earnings. This is a second conservative assumption, since other income than

earnings may also pay taxes of a different type.

26

Table 5: Lifetime Earnings, City, Property and Sales Taxes: Comparison by Educational

Attainment. Breakdown by Gender and Ethnicity (Present Value at Age 23 at 3.5 Percent

Discount Rate)

High School Associate Associate versus High School

Total

233,303 398,703

165,400

Male

306,313 489,150

182,837

Female

161,736 338,061

176,325

White

307,819 487,093

179,274

Black

222,554 379,955

157,401

Hispanic

198,509 348,659

150,150

Other

183,738 345,891

162,152

In constant 2010 dollars. Columns may not sum to total due to rounding.

ReducedCostsofPublicServicestoTaxpayer

Benefits of additional education to taxpayers comprise not only higher tax revenues from

those with greater levels of educational attainment, but also reductions in the taxpayer cost of

public services. More specifically, if high school graduates are able to obtain associate degrees,

there is strong evidence that they will place fewer cost burdens on public services for health,

public assistance, and criminal justice. In this section, we review the evidence on these benefits.

Health

Considerable empirical literature has summarized the relations between education and

health (e.g. Lleras-Muney, 2005; and Cutler & Lleras-Muney, 2010). Almost all measures of

health status are positively related to educational attainment. Education may improve health

through such mechanisms as healthier lifestyles in terms of nutrition, exercise, and reductions in

substance abuse; better health decisions because of better knowledge and more scientific ways of

addressing health needs; and the obvious possibility that more education may be associated with

other social advantages that correlate with better health. In an attempt to causally account for the

statistical relation between education and health, Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2010) find that a

substantial portion of the education advantage is due to knowledge and cognitive ability. To

estimate the public cost savings on health from receipt of associate degrees, we use public data

sources on public medical expenditures by educational level.

More specifically, we estimate the relationship by drawing on the Medical Expenditures

Panel Survey-2008 (MEPS), which is a nationally representative dataset, but we limit our

analysis to data for individuals residing in the Northeast region, within a metropolitan statistical

area (MSA). Importantly, the measurement of the educational variables in MEPS is recorded at

the time the individual joined the study. This means that if the individual earned any educational

credential afterwards, his educational attainment would be under-reported. In addition to that, the

potential classification of education varies slightly from the one ACS employs. In this case, the

survey reports years of education of the individuals rather than degree received. Since the degree

27

is not reported in these data, we converted 12 years of education to a high school equivalent and

14 years of education to an associate degree, providing an approximation for purposes of

computing public health costs.

Table 6 documents the association between educational attainment and some health

indicators in terms of enrollment and coverage by public health services. The two principal

public sources of spending on health costs are Medicaid and Medicare. Medicare is a federal

program that covers those 65 years and over, as well as those with chronic disabilities (without

age restriction). For populations under 65 in this analysis, the payments are limited to chronic

disabilities without respect to income. Medicaid is a program for low-income recipients, funded

by both federal and State taxpayers. Table 6 shows that the percentage of the general population

covered by each program is greater for high school completers than for associate degree

graduates. We remind the reader that these educational distinctions are approximate and based

upon the years of educational attainment because the data source does not specify the degrees

attained.

Table 6: Health Coverage Indicators by Educational Attainment

12 Years of Education

(High School)

2 Years of College

(Associate)

Percentage ever covered by Medicaid 21.4% 15.5%

Percentage ever covered by Medicare 6.2% 4.4%

Percentage with positive expenditures paid by Medicaid 19.6% 13.8%

Percentage with positive expenditures paid by Medicare 8.4% 5.4%

Source: MEPS-2008; unweighted means, individuals in the Northeast region, within a MSA, ages 23-65.

Similar relationships are documented using ACS 2008-2010, for individuals based in

New York City (Table 7), which allows us to provide a breakdown by gender and race.

Differences in coverage by public sources are greater for women than for men. The higher

percentage of Medicare recipients among the high school graduates than the associate group is

due to a higher proportion of Medicare eligible persons with chronic disabilities.

Table 7: Health Coverage Indicators by Educational Attainment. Breakdown by Gender

and Race

Percentage Covered by

Public Funding

Percentage Covered by

Medicaid

Percentage Covered by

Medicare

High School Associate High School Associate High School Associate

Total

27.8% 19.5%

24.4% 17.2%

5.2% 3.0%

Men 23.1% 17.2% 19.6% 14.3% 4.7% 3.3%

Women 32.5% 21.3% 29.2% 19.3% 5.6% 2.8%

White 22.4% 14.2% 17.0% 11.1% 6.6% 4.2%

Black 28.5% 20.8% 25.3% 18.3% 5.3% 3.0%

Hispanic 30.5% 24.5% 28.0% 23.0% 4.6% 2.2%

Other 31.9% 19.6% 30.3% 17.7% 3.0% 2.1%

Source: ACS 2008-2010, weighted means, individuals 23-65 in New York City.

28

Table 8 shows the present value at age 23 of total health expenditures by educational

attainment. These lifetime medical expenditures are calculated using MEPS-2008, for individuals

living within a MSA. We consider all individuals, with positive or zero health expenditures

(unweighted), ages 23-65. All amounts are expressed in 2010 constant dollars. The table shows

the breakdown by source of payment. Total public health expenditures of individuals with an

associate degree are, on average, about $15,000 in present value at age 23. Total public health

expenditures for individuals who completed high school (or with 12 years of education) are

about $20,000, about one-third higher than for those with the associate degree. Coverage of

Medicare for those under 65 is limited to chronic disease and is not restricted by income. It is

similar for both groups, although associate degree recipients may be better informed about this

coverage. On average, a person with an associate degree costs $5,000 less in public health

expenses than a person who completed high school, with most of the difference found in

Medicaid coverage. If an additional 1,000 new associate degrees can be gained by expanding

ASAP, the savings to the tax payer from subsidized health care alone would be over $5 million.