44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 3 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 3 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 1 16-MAY-22 16:37

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY

LAW REVIEW

V

OLUME

97 M

AY

2022 N

UMBER

2

ARTICLES

MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW

CREATIVITY*

A

MY

A

DLER

† & J

EANNE

C. F

ROMER

‡

* Timoth´ee Chalamet, Wes Anderson, Tilda Swinton and Bill Murray at Cannes, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/timothee-chalamet-wes-anderson-tilda-

swinton-and-bill-murray-at-cannes [https://perma.cc/PF2D-KC2A].

† Emily Kempin Professor of Law, New York University School of Law.

‡ Professor of Law, New York University School of Law; Faculty Co-Director,

Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy. We thank Cynthia Adler, Arnaud Ajdler,

Audrey C. Ajdler, Eric S. Ajdler, Olivia E. Ajdler, Rachel E. Barkow, Sunneal Bedi,

Barton C. Beebe, John Berton, Mala Chatterjee, James M. Chen, Kevin E. Davis, Charles

Duan, Brian L. Frye, Kristelia A. Garc´ıa, Clayton P. Gillette, Patrick Goold, Laura A.

Heymann, Samuel Issacharoff, Amy L. Landers, Stacey M. Lantagne, Mark A. Lemley,

Florencia Marotta-Wurgler, Michael Meurer, Peter Nicolas, Sean A. Pager, Amanda Reid,

Harry A. Robbins, Elizabeth L. Rosenblatt, Jennifer E. Rothman, Matthew Sag, Pamela

453

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 3 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 3 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 2 16-MAY-22 16:37

454 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

Memes are the paradigm of a new, flourishing creativity. Not only are these cap-

tioned images one of the most pervasive and important forms of online creativity,

but they also upend many of copyright law’s fundamental assumptions about crea-

tivity, commercialization, and distribution. Chief among these assumptions is that

copying is harmful. Not only does this mismatch threaten meme culture and expose

fundamental problems in copyright law and theory, but the mismatch is even more

significant because memes are far from an exceptional case. Indeed, memes are a

prototype of a new mode of creativity that is emerging in our contemporary digital

era, as can be seen across a range of works. Therefore, the concern with memes

signals a much broader problem in copyright law and theory. This is not to say that

the traditional creativity that copyright has long sought to protect is dead. Far from

it. Both paths of creativity, traditional and new, can be vibrant. Yet we must be

sensitive to the misfit between the new creativity and existing copyright law if we

want the new creativity to continue to thrive.

I

NTRODUCTION

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 456

R

I. C

OPYRIGHT ON

C

REATIVITY

, C

OMMERCIALIZATION

,

AND

D

ISTRIBUTION

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 459

R

A. Creativity Without Copying . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 462

R

B. Morality and Economics of Copying . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 465

R

C. Profiting from Copyright . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 466

R

D. Idea and Expression as Distinct . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 467

R

E. The Long Duration of Copyright . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 469

R

F. Choosing Third Parties as Licensees . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 470

R

G. The Author’s Centrality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 472

R

II. M

EMES

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 473

R

A. Overview. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 474

R

B. Why Memes Matter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 477

R

1. Newness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 479

R

a. New Content . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 480

R

b. Recontextualization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 481

R

c. Combinations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 482

R

2. Common Culture, Common Ground . . . . . . . . . . . . 483

R

3. Participatory Culture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 484

R

4. The Attention Economy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 487

R

5. The Dangers of Memes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 489

R

C. Copyright Claims for Memes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 492

R

Samuelson, Paul J. Sauerteig, Dalindyebo Shabalala, Jessica M. Silbey, Cathay Y.N. Smith,

Christopher Jon Sprigman, Madhavi Sunder, Naveen Thomas, Jacob Victor, Jeremy

Waldron, Joseph H.H. Weiler, Christopher Yoo, and participants at workshops at Drexel

University Thomas R. Kline School of Law, Michigan State University College of Law,

New York University School of Law, the Sixth Copyright Scholars Roundtable, the 2021

Intellectual Property Scholars Conference, and the 2020 Works in Progress in Intellectual

Property Colloquium for their attention-getting comments. Thanks to Siddharth

Anandalingam and Atreya Mathur for extraordinary research assistance. The authors

gratefully acknowledge support from the Filomen D’Agostino and Max E. Greenberg

Research Fund. Copyright

2022 by Amy Adler & Jeanne C. Fromer.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 4 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 4 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 3 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 455

1. Litigation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 492

R

2. Credit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 500

R

3. Licensing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 502

R

III. H

OW

M

EMES

U

PEND

C

OPYRIGHT

’

S

N

OTIONS OF

C

REATIVITY

, C

OMMERCIALIZATION

,

AND

D

ISTRIBUTION

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 504

R

A. The Norms of Copying and Transformation . . . . . . . . 505

R

1. Copying. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 506

R

2. Transformation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 509

R

B. The Creation of Value for Underlying Works

Through Copying . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 510

R

C. Indirect Monetization of Works . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 511

R

D. Line Between Commercial and Non-Commercial

Activity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 513

R

E. Breakdown of Idea-Expression Distinction . . . . . . . . . . 515

R

F. Scale and Pace of Copying . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 516

R

G. Staleness of Memes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 517

R

H. Selective Enforcement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 518

R

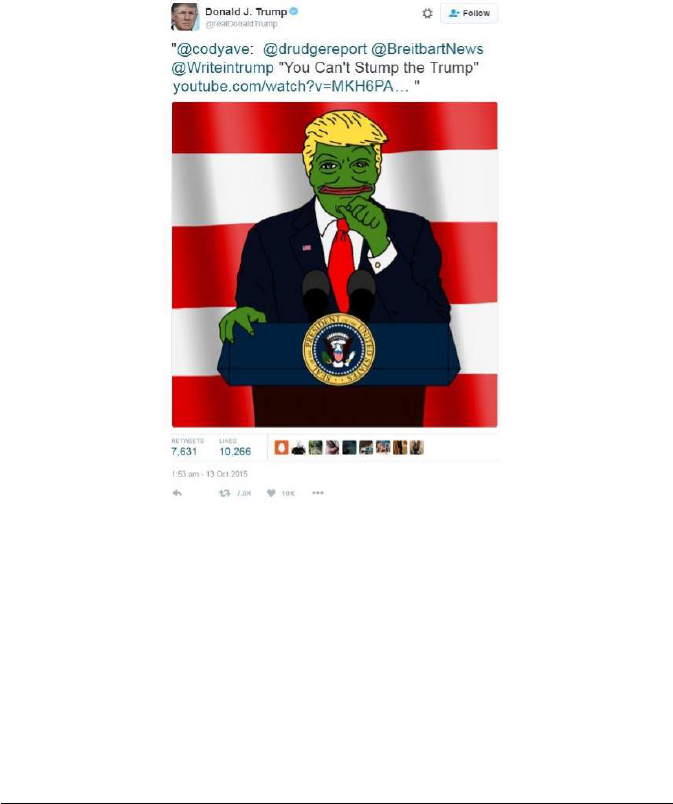

I. The Centrality of the Meme, Not the Author . . . . . . . . 519

R

IV. H

OW

S

HOULD

C

OPYRIGHT

L

AW

T

HINK

A

BOUT

M

EMES

? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 524

R

A. Keep Copyright Law Away from Memes? . . . . . . . . . . 525

R

B. An Attribution Regime? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 529

R

C. A Shortened Duration? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 532

R

D. A Narrowed Copyright Scope? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 534

R

E. Addressing Selective Enforcement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 536

R

1. The Worry of Forcing Creators to Allow

Universal Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 539

R

2. The Worry of Selective Silencing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 540

R

a. Nearly Everyone Gets to Use a Meme . . . . . 541

R

b. Except a Select Few . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 542

R

V. B

EYOND

M

EMES

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 545

R

A. Traditional Works Can Be Like Memes . . . . . . . . . . . . . 546

R

B. Memes as a Paradigm of a New Model of

Creativity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 550

R

C. Trying to Make Memes More Like Traditional

Works. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 561

R

C

ONCLUSION

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 563

R

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 4 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 4 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 4 16-MAY-22 16:37

456 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

I

NTRODUCTION

1

Dating back centuries to its earliest enactments, copyright law

has longstanding, built-in notions about creativity, commercialization,

and distribution of creative works that memes turn on their head in

critical ways. Copyright law is constructed on many assumptions

flowing from its base premise that copyright’s exclusive rights to

authors can encourage them to create and distribute socially valuable

creative works by preventing third-party copying of these works.

2

Central among them are the assumptions that people can generally

create desirable works without much copying, that authors want their

works not to be copied without their permission because otherwise

they will be harmed and disincentivized to create, and that authors

can make money directly off their creative works by exercising their

exclusive rights. Additionally, copyright law dictates that expression

should be protected and ideas should be freely available for reuse,

presuming that idea and expression are distinct. The law also is predi-

cated on the view that authors will have a long period over which to

recoup value for their works, and these works can be valuable for a

very long time. Copyright law also supposes that authors can and

should decide which third parties get to use their works and when and

whether to enforce their rights against third parties who have copied.

Finally, copyright law assumes that authors can easily be identified

1

See How It Started vs. How It’s Going, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://

knowyourmeme.com/memes/how-it-started-vs-how-its-going [https://perma.cc/LM76-

YV7K] (explaining the format of the “How It Started vs. How It’s Going” type of meme).

2

See infra Part I.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 5 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 5 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 5 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 457

and are central figures who deserve to get the copyright reward for a

work.

Yet in the context of memes spread over the internet, these

assumptions break down in significant ways. For one thing, not only

do meme creators typically want to be copied as much as possible,

they also usually want their works to be transformed by third parties

in untold ways. The copying of memes tends to create significant value

for, rather than detract from, the underlying works on which they are

based. Memes also shatter copyright’s assumption that creative works

are directly monetizable, as memes are usually indirectly monetizable.

The world of memes transcends the line between commercial and

noncommercial activity, while copyright law treats these realms as dis-

tinct. Additionally, memes expose that expression in one context can

become idea in another context, breaking down copyright law’s dis-

tinct categories of unprotectable idea and protectable expression.

Also characteristic of memes is an exponential scale and pace of cop-

ying, which concomitantly expedites the staleness of existing works

and the pace of creation of new works. Moreover, the selective

enforcement that copyright law assumes is turned on its head by the

broad scale of permitted or tolerated copying, as almost all can copy a

work and only a very select few are denied permission to use the

underlying work. Finally, whereas copyright law assumes the cen-

trality of the author, in meme culture the work itself takes on a pri-

mary role over the author, who often cannot even be easily identified.

These features of memes reflect a new creativity that has progressed

far beyond the creativity analyzed at the beginning of the twenty-first

century for user-generated content.

Although memes are often designed to be eye-catching and

funny, they are serious and important in today’s world as one of the

most frequently created and shared categories of creative works on

the internet, especially on social media.

3

As such, the fact that they

upend so many of copyright law’s central assumptions of creativity,

commercialization, and distribution is worthy of attention. If meme

culture is worth safeguarding, attempts to enforce copyright law as is

with regard to memes are inappropriate given the substantial discon-

nect between memes and copyright law’s assumptions. Therefore, cop-

3

See infra Part II; see also David Ryan Polgar, Why Understanding Memes Is

Important to Grasping What People Are Really Saying in 2020, F

ORBES

(June 4, 2020),

https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidryanpolgar/2020/06/04/why-understanding-memes-and-

internet-humor-is-important-to-grasping-what-people-are-really-saying-in-2020 [https://

perma.cc/88GK-YEPR] (recognizing memes as a component of “the language people are

speaking on the web”).

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 5 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 5 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 6 16-MAY-22 16:37

458 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

yright law and theory must either be left to the wayside or refashioned

to account for memes.

But the problem goes well beyond memes. Indeed, memes herald

a much larger shift that is underway in contemporary creativity across

a range of areas, including music, dance, and visual art. As we show,

the problems that memes present are of increasing and widespread

significance to contemporary creators. This emerging creativity shares

multiple characteristics of memes and similarly defies copyright’s core

assumptions. By mapping out the dramatic disconnect between

memes—a paradigm of contemporary creativity—and copyright law

and theory, we can reflect back on the increasing outdatedness of cop-

yright’s core. We conclude by observing that there now seems to be

two paradigms of creativity—the traditional model and what we call

the “new creativity”—that can both remain extant, vibrant, and dis-

tinct, even though they are interconnected and influence one another.

Copyright law better fits with the traditional model but is a misfit to

the new creativity.

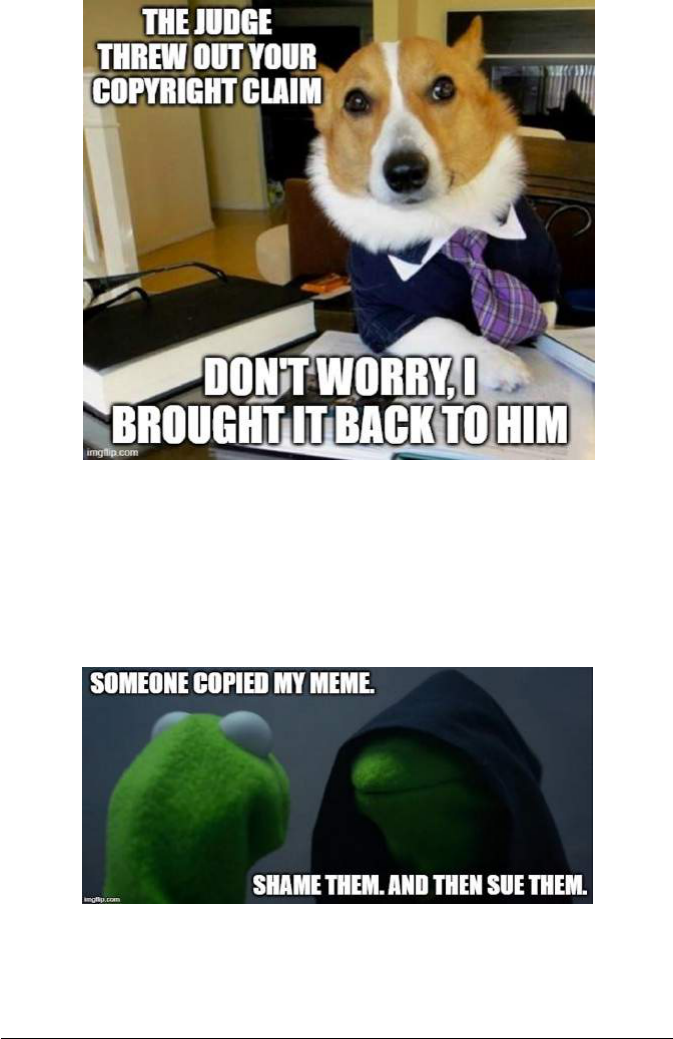

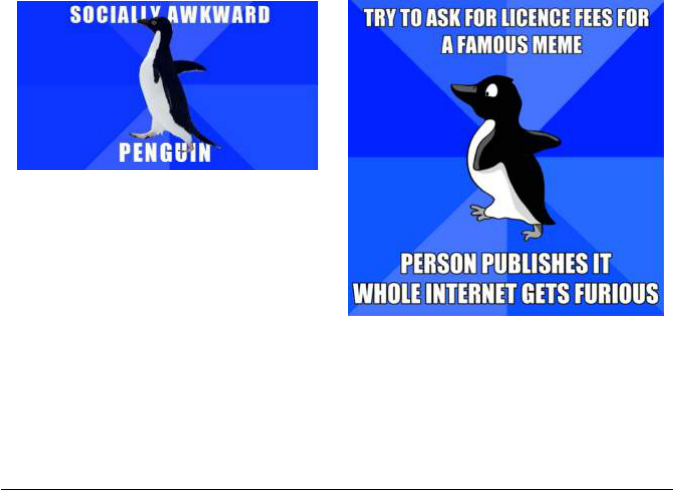

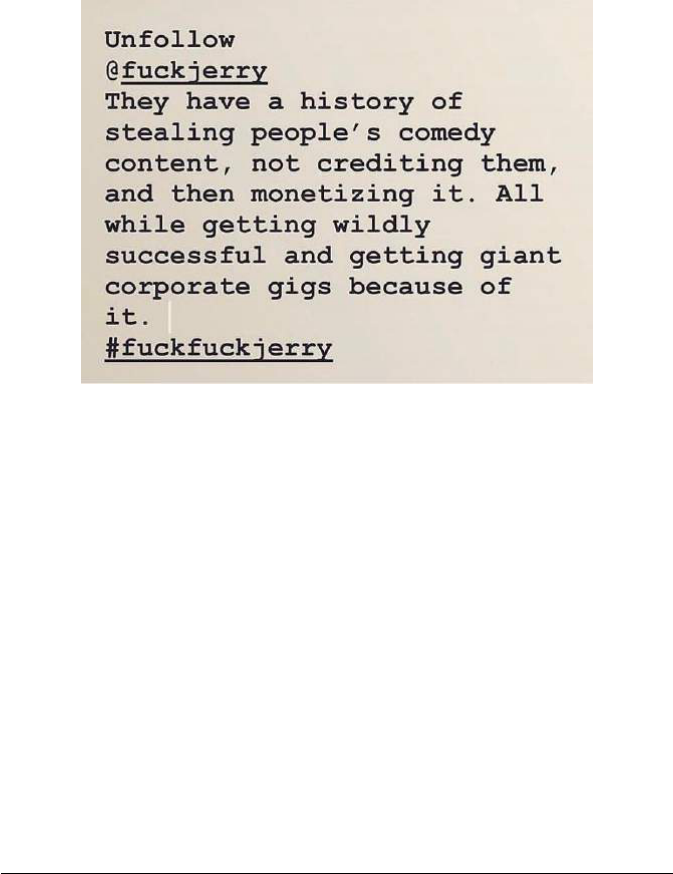

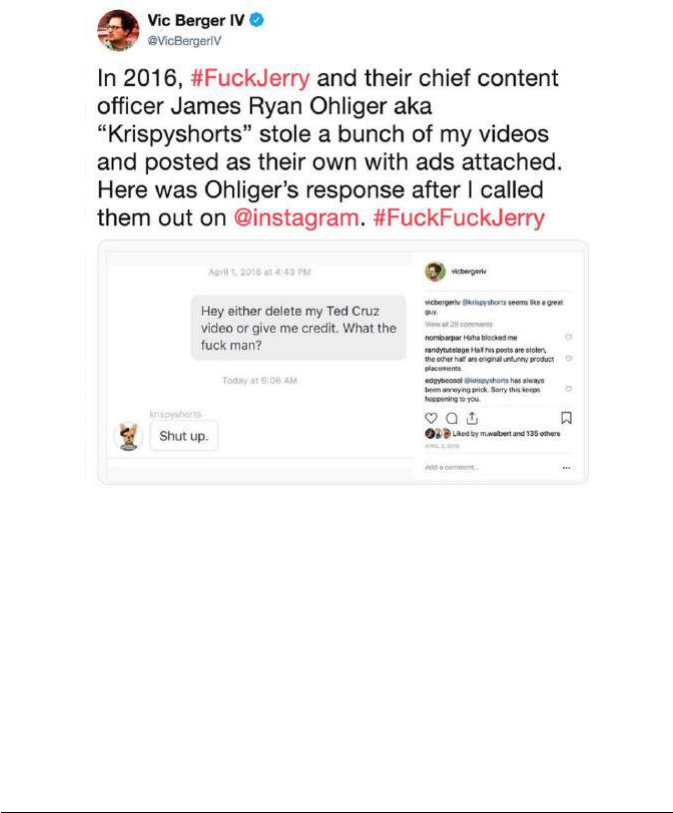

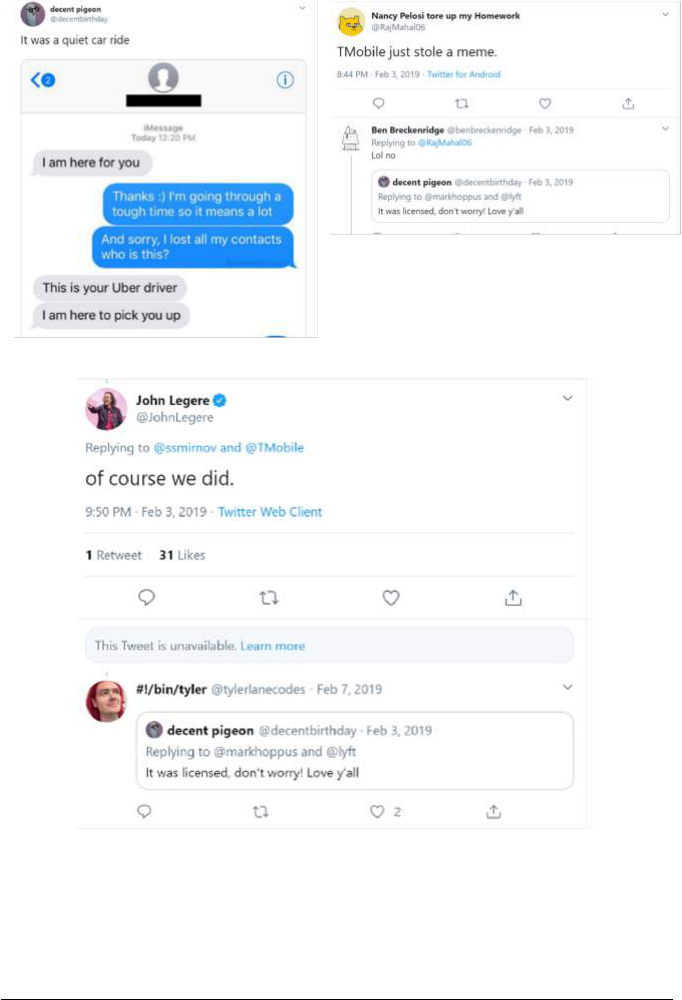

This Article explores these issues, organizing itself around a

series of memes we created that themselves reflect on memes.

4

Part I

sets forth the basic tenets of copyright law on creativity, commerciali-

zation, and distribution. Part II offers an overview of memes, presents

an argument for their significance, and outlines their current treat-

ment under copyright law. In Part III, we show how memes pose a

fundamental challenge to copyright law and theory by violating the

central copyright principles of creativity, commercialization, and dis-

tribution. Having established the disconnect between copyright law

and memes, Part IV considers whether and how copyright law could

be modified to account for memes. In Part V, we argue that memes

are far from a sui generis exception to the premises of copyright law.

Instead, memes are a prototype of a new mode of creativity that is

emerging in our contemporary digital era, as can be seen across a

range of works. Therefore, the concern with memes signals a much

broader problem in copyright law and theory.

4

The memes in this Article were made using Meme Generator,

IMGFLIP

, https://

imgflip.com/memegenerator [https://perma.cc/73D4-S4TF]. Each meme in this Article is

captioned with a corresponding section heading and footnoted with a source documenting

the meme’s background.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 6 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 6 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 7 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 459

I

C

OPYRIGHT ON

C

REATIVITY

, C

OMMERCIALIZATION

,

AND

D

ISTRIBUTION

5

We launch our exploration of memes with background on copy-

right law’s deep-rooted assumptions of creativity, commercialization,

and distribution. These assumptions stem from copyright law’s over-

arching goal of encouraging the creation and distribution of expressive

works deemed to be socially valuable by providing their authors with

exclusive rights against copying.

In particular, American copyright law protects “original works of

authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression,” including lit-

erary works, visual works, sound recordings, and movies.

6

A copyright

holder receives, among other things, the exclusive right to reproduce

the work, distribute copies, and prepare derivative works,

7

typically

until seventy years after the author’s death.

8

Copyright protection

extends to the expression of particular ideas rather than to the ideas

5

Grumpy Grandpa, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/

grumpy-grandpa [https://perma.cc/Z7EQ-U4S8].

6

17 U.S.C. § 102(a).

7

Id. § 106.

8

Id. § 302(a).

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 6 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 6 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 8 16-MAY-22 16:37

460 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

themselves.

9

Yet protection reaches well beyond the actual work to

works that are copied and substantially similar,

10

“else a plagiarist

would escape by immaterial variations.”

11

Utilitarianism is the dominant theory underpinning American

copyright law.

12

According to this theory, copyright law provides

authors the incentive of exclusive rights for a limited duration to moti-

vate them to create and distribute culturally valuable works.

13

Without this incentive, the theory goes, authors might not invest the

time, energy, and money necessary to create and distribute these

works because they might be copied cheaply and easily by free-riders,

eliminating the ability of authors to profit from their works.

14

Pursuant to utilitarian thinking, copyright law confers rights that

are designed to be limited in time and scope.

15

If the rights provided

are excessive, social welfare would be diminished.

16

For one thing,

exclusive rights in intellectual property can diminish competition by

allowing a rightsholder to charge a premium for access and ultimately

limit these valuable works’ diffusion to society at large.

17

For another,

given that knowledge is frequently cumulative, society benefits when

creators are permitted to build on previous artistic creations to gen-

erate new works.

18

For these reasons, copyright law ensures both that

the works it protects fall into the public domain in due course and that

third parties are free to use protected works for certain socially valu-

9

Id. § 102(b); see, e.g., Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp., 45 F.2d 119, 121 (2d Cir.

1930) (explaining that creators do not have a property right in ideas that exist “apart from

their expression”).

10

Corwin v. Walt Disney Co., 475 F.3d 1239, 1253 (11th Cir. 2007).

11

Nichols, 45 F.2d at 121.

12

See Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enters., 471 U.S. 539, 557–58 (1985)

(reviewing past precedents characterizing copyright law as the best way to advance public

welfare); Shyamkrishna Balganesh, Foreseeability and Copyright Incentives, 122 H

ARV

. L.

R

EV

. 1569, 1576–77 (2009) (“[C]opyright law in the United States has undeniably come to

be understood almost entirely in utilitarian, incentive-driven terms.”); Jeanne C. Fromer,

Expressive Incentives in Intellectual Property, 98 V

A

. L. R

EV

. 1745, 1750–52 (2012)

[hereinafter Fromer, Expressive Incentives] (“The Supreme Court, Congress, and many

legal scholars consider utilitarianism the dominant purpose of American copyright . . .

law.” (footnote omitted)); William M. Landes & Richard A. Posner, An Economic

Analysis of Copyright Law, 18 J. L

EGAL

S

TUD

. 325, 326 (1989) (noting that intellectual

property is distinguished by its “‘public good’ aspect”).

13

See Stewart E. Sterk, Rhetoric and Reality in Copyright Law, 94 M

ICH

. L. R

EV

. 1197,

1203 (1996).

14

Id. at 1204.

15

Mark A. Lemley, The Economics of Improvement in Intellectual Property Law, 75

T

EX

. L. R

EV

. 989, 997 (1997).

16

See id. at 996–97.

17

Id.

18

Id. at 997–98; see also Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 575–76

(1994) (discussing the policy benefits of the fair use doctrine, which limits a copyright

holder’s exclusive rights for certain socially beneficial uses).

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 7 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 7 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 9 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 461

able purposes.

19

In this way, a utilitarian theory of copyright law rests

on the premise that the benefit to society of creators crafting valuable

works in exchange for legal incentives offsets the social welfare

costs.

20

In recent years, scholars have questioned whether the copyright

incentive is necessary in the first instance to motivate people to create

expressive works. Some scholars have explored the vibrant expressive

activity occurring outside the realm of copyright, such as in cuisine,

stand-up comedy, and magic.

21

Others argue that in certain markets,

copyright law is unnecessary because the social norm of authenticity

incentivizes creativity.

22

Some scholars hypothesize that people would

create works absent copyright incentives, owing to intrinsic motivation

to do so.

23

Yet others think this skepticism is wrong or incomplete,

arguing that copyright’s incentive does encourage both creation and

distribution of works.

24

Indeed, rightly or wrongly, copyright’s incen-

tive theory remains front and center in copyright as currently

implemented.

With this background, we now explore how traditional copyright

theory and doctrine interrelate with the many assumptions copyright

law makes about creativity, commercialization, and distribution.

19

See Lemley, supra note 15, at 999.

20

Id. at 996–97.

21

See, e.g., Christopher J. Buccafusco, On the Legal Consequences of Sauces: Should

Thomas Keller’s Recipes Be Per Se Copyrightable?, 24 C

ARDOZO

A

RTS

& E

NT

. L.J. 1121

(2007); Emmanuelle Fauchart & Eric von Hippel, Norms-Based Intellectual Property

Systems: The Case of French Chefs, 19 O

RG

. S

CI

. 187 (2008); Dotan Oliar & Christopher

Sprigman, There’s No Free Laugh (Anymore): The Emergence of Intellectual Property

Norms and the Transformation of Stand-Up Comedy, 94 V

A

. L. R

EV

. 1787 (2008); Jacob

Loshin, Secrets Revealed: Protecting Magicians’ Intellectual Property Without Law, in L

AW

AND

M

AGIC

: A C

OLLECTION OF

E

SSAYS

123 (Christine A. Corcos ed., 2010).

22

See Amy Adler, Why Art Does Not Need Copyright, 86 G

EO

. W

ASH

. L. R

EV

. 313,

329–30 (2018) [hereinafter Adler, Why Art Does Not Need Copyright] (arguing that even if

we accept the utilitarian account of creativity, the necessary incentive for the creation of

visual art stems from the art market’s rigid norm of authenticity, and not at all from

copyright law).

23

E.g., Rebecca Tushnet, Economies of Desire: Fair Use and Marketplace Assumptions,

51 W

M

. & M

ARY

L. R

EV

. 513 (2009); Diane Leenheer Zimmerman, Copyrights as

Incentives: Did We Just Imagine That?, 12 T

HEORETICAL

I

NQUIRIES

L. 29 (2011). For a

survey of this literature and some theoretical and empirical skepticism about it, see

Christopher Buccafusco, Zachary C. Burns, Jeanne C. Fromer & Christopher Jon

Sprigman, Experimental Tests of Intellectual Property Laws’ Creativity Thresholds, 92 T

EX

.

L. R

EV

. 1921, 1931–43 (2014).

24

See Buccafusco, Burns, Fromer & Sprigman, supra note 23, at 1976, 1978–79; see also

Julie E. Cohen, Copyright as Property in the Post-Industrial Economy: A Research Agenda,

2011 W

IS

. L. R

EV

. 141, 143 (embracing the idea that creativity is not motivated by

copyright protections, but arguing that copyright is necessary for the efficient exploitation

of creative work by industry).

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 7 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 7 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 10 16-MAY-22 16:37

462 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

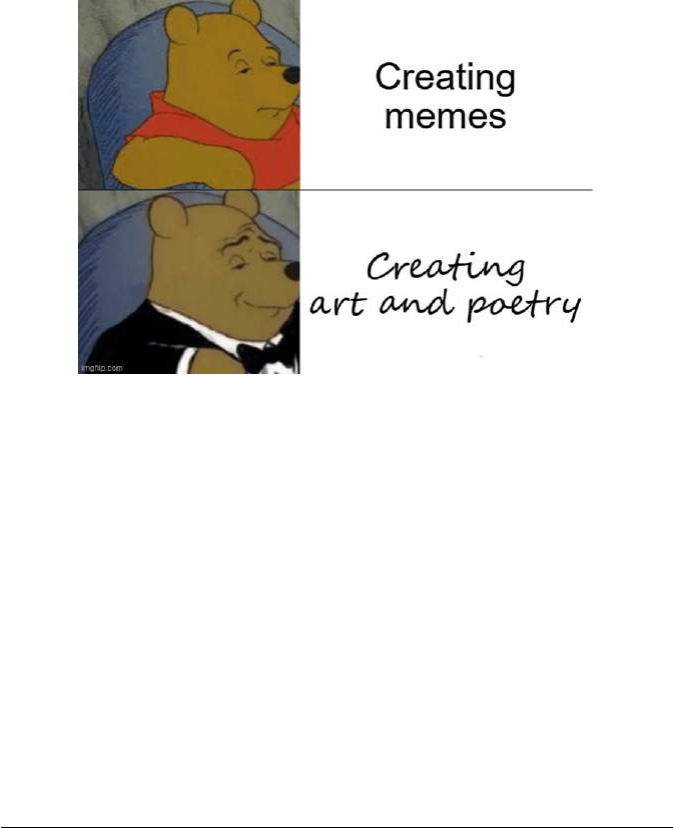

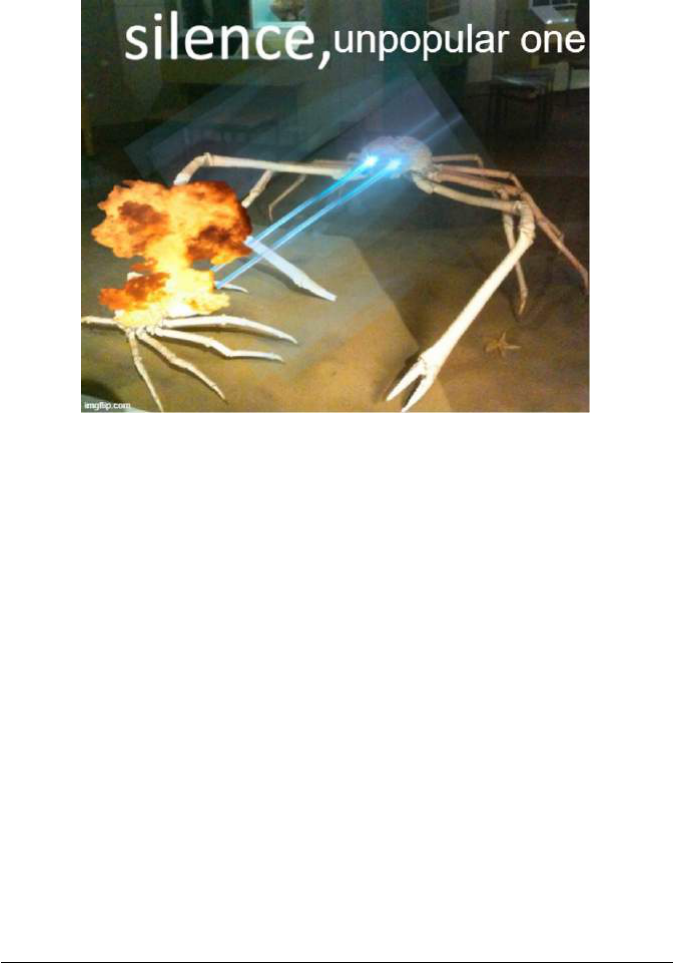

A. Creativity Without Copying

25

Copyright law is premised on authors producing creative works

without copying. Even though copyright law sometimes condones cop-

ying, in the main it is antagonistic to copying because of copyright’s

goals.

Two of copyright law’s central requirements underscore the law’s

rejection of creativity through copying. Consider first copyright’s orig-

inality requirement, which is a prerequisite for copyright protection.

26

The Supreme Court has held that work is original so long as it “was

independently created by the author (as opposed to copied from other

works), and that it possesses at least some minimal degree of crea-

tivity.”

27

A work must merely evidence “intellectual production, . . .

thought, and conception.”

28

Originality does not necessarily require

true novelty; a minimally creative work is protectable even if there is a

nearly identical work, so long as the other work was not copied.

29

As

Judge Learned Hand observed, “[I]f by some magic a man who had

25

Left Exit 12 Off Ramp, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/

left-exit-12-off-ramp [https://perma.cc/PKW2-4MAK].

26

17 U.S.C. § 102(a) (“Copyright protection subsists . . . in original works of authorship

fixed in any tangible medium of expression.”).

27

Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 345 (1991).

28

Id. at 362 (quoting Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 59–60

(1884)).

29

Id. at 345–46.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 8 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 8 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 11 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 463

never known it were to compose anew Keats’s Ode on a Grecian Urn,

he would be an ‘author,’ and, if he copyrighted it, others might not

copy that poem, though they might of course copy Keats’s.”

30

The

originality requirement as a threshold for copyright protection is thus

premised on an author’s independent creation of a work without

copying.

Now consider copyright law’s rule for infringement. A defen-

dant’s acts can be condemned as infringing only if the defendant actu-

ally copied the plaintiff’s copyrighted work in some capacity.

31

Hence,

a defendant’s independent creation is a full defense to an infringe-

ment claim.

32

That said, not all copying is ultimately forbidden. As the

Ninth Circuit has explained, “To infringe, the defendant must . . . copy

enough of the plaintiff’s expression . . . to render the two works sub-

stantially similar.”

33

Both copyright protection and infringement liability are accord-

ingly grounded in the notion that copying is harmful, something to be

avoided and condemned. One cannot garner copyright protection in

the first place by creating a work that copies from a preexisting work,

and one might be condemned to infringement liability if one has

copied, particularly if one has copied too much.

Both of these crucial aspects of copyright law underpin its

thinking about creativity: Copyright law seeks to and will encourage

creativity, but only that which occurs without much copying, if any.

That is, copyright law assumes that the socially valuable works it seeks

to encourage should occur without copying from others and will not

be considered infringing if they are not copied.

34

One might under-

stand this as a financial matter: It makes little sense to provide copy-

right’s incentives to someone who copies an existing work or to

condemn a third party who has not actually copied from an existing

work.

35

Otherwise, if copiers were granted the privileges of copyright,

the copyright incentive would be blunted by allowing secondcomers to

copy from and undercut the copyright incentive provided to the

firstcomer.

36

This antipathy toward copying can also be understood

30

Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corp., 81 F.2d 49, 54 (2d Cir. 1936).

31

See Design Basics, LLC v. Signature Constr., Inc., 994 F.3d 879, 887 (7th Cir. 2021).

32

See Skidmore v. Zeppelin, 952 F.3d 1051, 1064 (9th Cir. 2020).

33

Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc., 883 F.3d 1111, 1117 (9th Cir. 2018) (citing Mattel, Inc. v.

MGA Ent., Inc., 616 F.3d 904, 913–14 (9th Cir. 2010)) (internal marks omitted).

34

See Jeanne C. Fromer, A Psychology of Intellectual Property, 104 N

W

. U. L. R

EV

.

1441, 1443–44 (2010) [hereinafter Fromer, A Psychology of IP] (explaining and analyzing

the creativity that copyright and patent laws seek to promote).

35

See W

ILLIAM

M. L

ANDES

& R

ICHARD

A. P

OSNER

, T

HE

E

CONOMIC

S

TRUCTURE OF

I

NTELLECTUAL

P

ROPERTY

L

AW

85–91 (2003).

36

See id. at 87–91.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 8 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 8 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 12 16-MAY-22 16:37

464 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

morally: Copyists are culpable—such as for appropriating someone

else’s creative labor—and ought to be discouraged.

37

Yet copyright’s reality is more complex. Copyright law sometimes

condones copying, most notably with regard to fair uses of a work.

38

The fair use doctrine is thought to stimulate the production of creative

works that do not undercut the value of the original copyrighted work

too much.

39

It does so by enabling third parties to create culturally

valuable works that must copy from the original work in some

capacity in order to succeed, often transforming it.

40

As suggested by

the statutory directive on fair use

41

and elaborated in case law, some

prototypical cases include news reporting, critical reviews, and paro-

dies.

42

Wendy Gordon has theorized that “fair use [has been used] to

permit uncompensated transfers that are socially desirable but not

capable of effectuation through the market.”

43

Examples include par-

odies that might cast an unfavorable light on an original work or uses

for which high transaction costs would discourage licensing arrange-

ments with the copyright owner.

44

This particularized authorization of some copying coincides with

scholarly recognition that copying can encourage creativity. For one

thing, scholars appreciate that artists may create by building on

others’ work or learn from existing works to create new work.

45

More

directly, scholars and courts recognize how important copying can be

to creating important new works, whether it be contemporary art like

Richard Prince’s, Star Trek fan fiction, or a new software implementa-

37

See Mala Chatterjee, Lockean Copyright Versus Lockean Property, 12 J. L

EGAL

A

NALYSIS

136, 153 (2020) (explaining copyright law through the lens of Lockean theory);

Patrick R. Goold, Moral Reflections on Strict Liability in Copyright, 44 C

OLUM

. J.L. &

A

RTS

123 (2021) (exploring how intuitive moral evaluations about copying are challenged

and subverted by the strict liability rules in copyright doctrine).

38

See 17 U.S.C. § 107 (listing circumstances in which “the fair use of a copyrighted

work . . . is not an infringement of copyright”); supra note 18 and accompanying text.

39

See Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 577, 590–94 (1994) (discussing

how courts should consider market harms on the copyrighted work which result from the

copyright infringement in question).

40

See Pierre N. Leval, Commentary, Toward a Fair Use Standard, 103 H

ARV

. L. R

EV

.

1105, 1111–16 (1990) (arguing that whether or not the use of copyrighted material is

justified often depends on the extent to which the use of that material is transformative).

41

See 17 U.S.C. § 107 (listing non-exclusive factors to motivate a determination of fair

use).

42

See Campbell, 510 U.S. at 578–85 (parodies); Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v.

Nation Enters., 471 U.S. 539, 561 (1985) (news reporting); Sundeman v. Seajay Soc’y, Inc.,

142 F.3d 194, 206 (4th Cir. 1998) (critical review).

43

Wendy J. Gordon, Fair Use as Market Failure: A Structural and Economic Analysis

of the Betamax Case and Its Predecessors, 82 C

OLUM

. L. R

EV

. 1600, 1601 (1982).

44

Id. at 1633 (giving as one instance “the owner of a play [being] unlikely to license a

hostile review or a parody of his own drama” (footnote omitted)).

45

See, e.g., Fromer, A Psychology of IP, supra note 34, at 1461–62.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 9 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 9 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 13 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 465

tion of the Java application program interface.

46

Moreover, as we have

previously observed, in light of today’s internet age, “as the entire

archive of past creative works becomes more accessible, creators will

have access to more past works to build on and copying will likely play

an even more significant role in creativity.”

47

Despite this scholarly recognition that fair use exists as one

among several important statutory exceptions to copyright infringe-

ment,

48

the “exemption” framework implicitly makes default the

assumption that creativity must be without copying. Copying some-

times can be condoned and important in copyright law, but it is the

exception rather than the norm.

49

B. Morality and Economics of Copying

50

Copyright law’s antipathy toward copying raises the question of

why copying is not condoned as a general matter. Copyright law takes

46

See, e.g., Google LLC v. Oracle Am., Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1183 (2021) (Java); Amy Adler,

Fair Use and the Future of Art, 91 N.Y.U. L. R

EV

. 559, 567–72 (2016) [hereinafter Adler,

Fair Use] (contemporary art); Rebecca Tushnet, Legal Fictions: Copyright, Fan Fiction, and

a New Common Law, 17 L

OY

. L.A. E

NT

. L.J. 651 (1997) (fan fiction).

47

Amy Adler & Jeanne C. Fromer, Taking Intellectual Property into Their Own Hands,

107 C

ALIF

. L. R

EV

. 1455, 1530 (2019) (footnote omitted).

48

See 17 U.S.C. §§ 107–122 (including, among others, reproductions by libraries and

archives (§ 108), ephemeral recordings (§ 112), and noncommercial broadcasting (§ 118)).

49

Cf. Shyamkrishna Balganesh, The Obligatory Structure of Copyright Law:

Unbundling the Wrong of Copying, 125 H

ARV

. L. R

EV

. 1664, 1666–74 (2012) (showing that

“much of copyright’s analytical work is done through its creation and maintenance of a

‘duty not to copy’”).

50

Steven Crowder’s “Change My Mind” Campus Sign, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://

knowyourmeme.com/memes/steven-crowders-change-my-mind-campus-sign [https://

perma.cc/N6WP-SPT3].

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 9 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 9 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 14 16-MAY-22 16:37

466 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

the position that copying someone’s creative work is generally

harmful, both economically and morally. For one thing, copying is

thought to be economically harmful in that it undermines the incen-

tive of creators to make valuable works.

51

Under this thinking, third

parties’ unauthorized copying undermines the original author’s exclu-

sive rights by allowing copiers to make the same work at a marginal

cost by avoiding the costs of creation.

52

Moreover, copying others’

work is condemned by some courts as lazy

53

and by some scholars as

immoral.

54

C. Profiting from Copyright

55

If copyright is thought to serve as an incentive to create, it func-

tions by awarding exclusive rights such that authors may directly

profit off their creative works. That is, authors can invoke copyright to

stop others from exercising any of copyright’s exclusive rights,

including reproducing, distributing, and publicly performing a work.

56

Authors can exercise these rights themselves,

57

thereby selling access

to their works in various ways. Because these rights are exclusive,

51

See L

ANDES

& P

OSNER

, supra note 35, at 85–91.

52

Id.

53

See, e.g., Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation LLC, 766 F.3d 756, 759 (7th Cir. 2014) (“The fair-

use privilege . . . is not designed to protect lazy appropriators.”); cf. Campbell v. Acuff-

Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 580 (1994) (observing that a fair use claim is less strong

when “the alleged infringer merely uses [the underlying work] to get attention or to avoid

the drudgery in working up something fresh”).

54

Balganesh, supra note 49, at 1679; Abraham Drassinower, Copyright Infringement as

Compelled Speech, in N

EW

F

RONTIERS IN THE

P

HILOSOPHY OF

I

NTELLECTUAL

P

ROPERTY

203, 205 (Annabelle Lever ed., 2012) (“[U]nauthorized use of another’s speech . . . den[ies

an author] the very autonomy manifested in and through her speech.”).

55

Shut Up and Take My Money!, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/

memes/shut-up-and-take-my-money [https://perma.cc/A8B8-XAXG].

56

17 U.S.C. § 106.

57

Id.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 10 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 10 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 15 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 467

authors can typically sell their works at higher prices than they would

be able to without them.

58

Again, copying may interfere with an

author’s profits from these exclusive rights, thereby inflicting eco-

nomic (and moral) harms. By privatizing what would otherwise be a

freely copyable public good through the operation of law, copyright

makes protectable works monetizable.

D. Idea and Expression as Distinct

59

Beyond creativity and copying, copyright law has further rules

about what material is and is not protectable. In particular, copyright

law extends protection only to the expression of ideas; ideas them-

selves remain in the public domain.

60

For example, the expression in a

play about star-crossed lovers would be copyrightable, but the idea of

star-crossed lovers would not.

61

As the Supreme Court has explained,

ideas are excluded from the scope of copyright protection so that they

can be left free for all to use as building blocks to create further

expression.

62

Courts attribute this principle to protecting First

Amendment values.

63

58

See Pamela Samuelson, Allocating Ownership Rights in Computer-Generated Works,

47 U. P

ITT

. L. R

EV

. 1185, 1224–25 (1986).

59

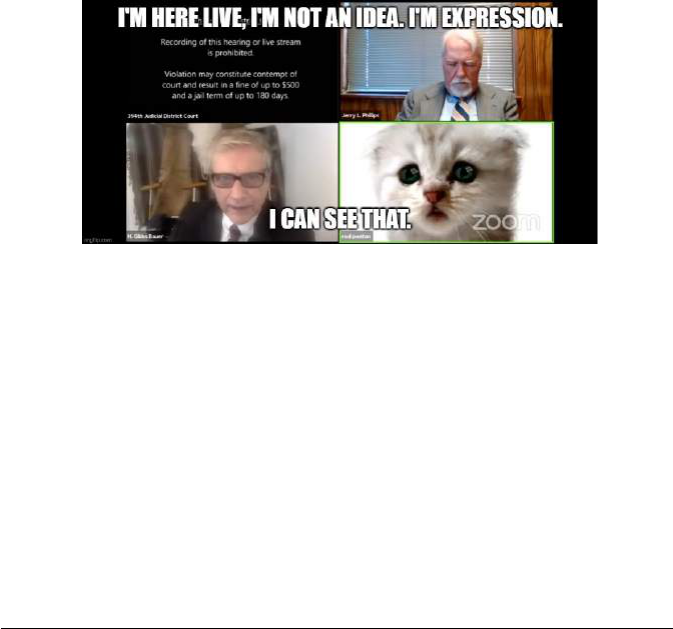

Zoom Cat Lawyer / I’m Not a Cat, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/

memes/zoom-cat-lawyer-im-not-a-cat [https://perma.cc/M6N7-42LA].

60

See supra note 9 and accompanying text.

61

See Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp., 45 F.2d 119, 121–22 (2d Cir. 1930).

62

See Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 349–50 (1991).

63

See Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enters., 471 U.S. 539, 556 (1985); cf.

Jeanne C. Fromer, An Information Theory of Copyright Law, 64 E

MORY

L.J. 71, 97–102

(2014) [hereinafter Fromer, Information Theory] (“[T]he basic building blocks of

expression ought to be left freely available . . . . It would be both inefficient and unfair to

grant rights in these basic components . . . just because one person happened to employ

them first. Doing otherwise would ultimately be detrimental to generating a robust body of

authored works.” (footnotes omitted)).

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 10 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 10 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 16 16-MAY-22 16:37

468 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

Courts and scholars find it hard to distinguish between idea and

expression.

64

As Learned Hand influentially set up the analysis:

Upon any work, . . . a great number of patterns of increasing gener-

ality will fit equally well, as more and more of the incident is left

out. The last may perhaps be no more than the most general state-

ment of what [a work] is about, and at times might consist only of its

title; but there is a point in this series of abstractions where they are

no longer protected, since otherwise the [author] could prevent the

use of his ‘ideas,’ to which, apart from their expression, his property

is never extended.

65

Judge Hand then concludes, “Nobody has ever been able to fix that

boundary, and nobody ever can.”

66

Even so, courts have established a

doctrinal framework of abstraction and filtration to distinguish idea

from expression.

67

Despite the difficulty of distinguishing between the two catego-

ries, copyright law understands the categories to be distinct: one pro-

tectable, the other not.

68

Star-crossed lovers are always an

unprotectable idea, whereas the words in a play about star-crossed

lovers are always expression and thus potentially protectable.

64

See, e.g., Nichols, 45 F.2d at 121 (developing a framework for determining

infringement when no actual expression of the copyrighted work is taken and used in the

allegedly infringing work); see also Neil Weinstock Netanel, Copyright and a Democratic

Civil Society, 106 Y

ALE

L.J. 283, 304 (1996) (“[W]hile the idea/expression dichotomy

makes sense in principle, it is notoriously malleable and indeterminate.”).

65

Nichols, 45 F.2d at 121.

66

Id.

67

See id. at 121–23 (breaking down the structure and different elements of the

defendant’s allegedly infringing work (abstraction) to separate protectable expression from

an unprotectable idea (filtration), and holding, based on only the unfiltered elements that

were expression, that the defendant’s motion picture did not infringe the plaintiff’s play);

see also Comput. Assocs. Int’l, Inc. v. Altai, Inc., 982 F.2d 693, 706–10 (2d Cir. 1992) (using

the abstraction-filtration framework to determine whether the nonliteral elements of two

computer programs were substantially similar).

68

Even while explicitly recognizing the interconnection between expression and idea,

copyright’s merger doctrine nevertheless assumes a distinction. According to this doctrine,

when there are only a very limited number of ways to express an idea, idea and expression

are thought to have merged, rendering the expression just as uncopyrightable as the idea.

See Morrissey v. Procter & Gamble Co., 379 F.2d 675, 678–79 (1st Cir. 1967). The

expression in such cases is not protectable because were it otherwise, copyright law would

effectively be providing protection to the idea. See id.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 11 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 11 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 17 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 469

E. The Long Duration of Copyright

69

If a work meets the various protectability requirements just dis-

cussed, it is typically protected by copyright law for a long time: gener-

ally, an author’s lifetime plus seventy years.

70

As a policy matter,

duration is premised on the period of time over which an author can

recoup value for their work.

71

As one of us has explained, Congress

has repeatedly extended copyright duration, asserting that it was

doing so to “account[] for increased average life expectancies for

authors and for the longer commercial life of works,” among other

reasons.

72

In fact, this duration can be so long that technologies of

dissemination and markets—such as the internet, social media, and

video cassettes—can develop in a way unforeseen to authors a century

or more ago when they first created their work.

73

69

This Meme Is from the Future, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/

memes/this-meme-is-from-the-future [perma.cc/ES49-32CU].

70

See supra text accompanying note 8.

71

See Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186, 205–08 (2003).

72

Fromer, Expressive Incentives, supra note 12, at 1799–1800.

73

See, e.g., Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers, Ltd. v. Walt Disney Co., 145 F.3d 481

(2d Cir. 1998) (interpreting contract when the composer’s original piece was licensed for a

movie’s use in theaters but was later released on video cassettes); Rey v. Lafferty, 990 F.2d

1379 (1st Cir. 1993) (construing contract terms when a television program based on a series

of book was later released on video cassette). For an argument that copyright law should

not protect unforeseeable markets, see generally Balganesh, supra note 12.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 11 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 11 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 18 16-MAY-22 16:37

470 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

Some argue that copyright protection lasts too long in ways that

undermine copyright’s goals, particularly because the commercial

value of works is not long enough to justify the increased costs that

copyright protection imposes on society. For example, Justice Breyer

expresses worry that too-long copyright duration imposes the cost of

“higher prices that will potentially restrict a work’s dissemination” on

society when “after 55 to 75 years, only 2% of all copyrights retain

commercial value.”

74

Similarly, Kristelia Garc´ıa and Justin McCrary

find in an empirical study that “for the average musical work, sales

drop sharply soon after release.”

75

Therefore, “for the average work,

the societal cost of strong copyright protection that goes beyond the

point of commercial viability outweighs the benefit to both creators

and consumers as the marginal return on this protection decreases

sharply.”

76

That said, the trend in copyright law since its earliest years

has been for copyright duration to be extended, never shrunk.

77

F. Choosing Third Parties as Licensees

78

Copyright law enables authors to transfer or license all or parts of

74

Eldred, 537 U.S. at 248, 254 (Breyer, J., dissenting) (citing Brief for Petitioners at 7,

Eldred, 537 U.S. 186 (2003) (No. 01-618); E

DWARD

R

APPAPORT

, C

ONG

. R

SCH

. S

ERV

.,

C

OPYRIGHT

T

ERM

E

XTENSION

: E

STIMATING THE

E

CONOMIC

V

ALUES

, C

ONGRESSIONAL

R

ESEARCH

S

ERVICE

R

EPORT FOR

C

ONGRESS

8, 12, 15, 16 (1998)).

75

Kristelia A. Garc´ıa & Justin McCrary, A Reconsideration of Copyright’s Term, 71

A

LA

. L. R

EV

. 351, 356 (2019).

76

Id.

77

See Fromer, Expressive Incentives, supra note 12, at 1799 (citing statutes); Sonny

Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, Pub. L. No. 105-298, 112 Stat. 2827 (1998) (codified

in scattered sections of 17 U.S.C.).

78

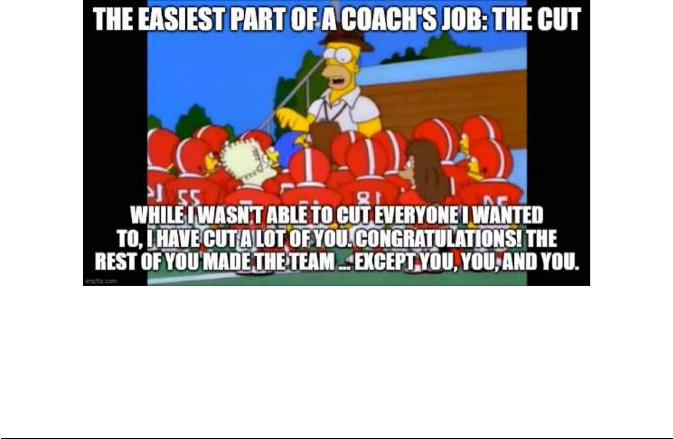

The Simpsons, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/subcultures/

the-simpsons [https://perma.cc/NZ4J-P7QN].

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 12 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 12 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 19 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 471

their exclusive rights to third parties.

79

The law also permits copyright

owners to enforce their rights by bringing an action for copyright

infringement.

80

These two aspects of copyright law imply that copy-

right owners get to decide which, if any, third parties can use their

works and when and whether to enforce their rights against third par-

ties who have copied their works without permission. Indeed, courts

have espoused the view that this is the copyright holder’s ultimate

choice. For instance, the Second Circuit has stated that copyright law

“must respect [the copyright holder’s] creative and economic choice”

to not exploit an aspect of their exclusive rights.

81

The copyright owner can grant a select few licenses that they

deem to be efficient. For example, an author of an English-language

book may grant a license to a particular translator to create a French-

language version of the book.

82

This is understood to be part and

parcel of the copyright incentive in the first instance, as a way to con-

trol who else, if anyone, can make works that might interfere with or

enhance the copyright holder’s market.

83

Moreover, even without

granting third parties permission to use a work, copyright owners may

tolerate infringing uses.

84

They might do so, as Tim Wu puts it, due to

“laziness or enforcement costs, a desire to create goodwill, or a calcu-

lation that the infringement creates an economic complement to the

copyrighted work.”

85

79

17 U.S.C. § 201(d) (“Any of the exclusive rights comprised in a copyright, including

any subdivision of any of the rights specified by [17 U.S.C. § 106], may be transferred . . .

and owned separately.”).

80

Id. § 501(b).

81

Castle Rock Ent., Inc. v. Carol Publ’g Grp., Inc., 150 F.3d 132, 146 (2d Cir. 1998)

(making this observation in a case in which the copyright holder of the Seinfeld television

series sued the maker of a trivia book about the series).

82

See Paul Goldstein, Derivative Rights and Derivative Works in Copyright, 30 J.

C

OPYRIGHT

S

OC

’

Y

U.S.A. 209, 227 (1983) (“[B]y securing exclusive rights to all derivative

markets, [17 U.S.C. § 106(2)] enables the copyright proprietor to select those towards

which it will direct investment.”).

83

See id.; cf. Jeanne C. Fromer & Mark A. Lemley, The Audience in Intellectual

Property Infringement, 112 M

ICH

. L. R

EV

. 1251, 1255 (2014) (arguing that copyright and

other intellectual property regimes “should require proof of both sufficient technical

similarity and market substitution” to find infringement).

84

See generally Tim Wu, Tolerated Use, 31 C

OLUM

. J.L. & A

RTS

617 (2008).

85

Id. at 619.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 12 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 12 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 20 16-MAY-22 16:37

472 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

G. The Author’s Centrality

86

A final assumption on which copyright law is premised is that the

author is central and can generally readily be identified to get their

copyright reward. Copyright law situates initial protection in a work’s

author, be the work a single-authored work, a joint work, or a work

made for hire.

87

This grant follows from the constitutional grant of

power to Congress to confer copyright protection on authors for their

writings.

88

An abundance of critical scholarship attacks the assumption that

the author ought to be the central figure in copyright law deserving of

the reward, particularly when there are many others, including editors

and audiences, who contribute to a work and its value.

89

Stewart Sterk

goes further to underscore how rhetoric of the author’s centrality to

works has helped create and expand copyright rights, even beyond

what is necessary to achieve copyright’s goals.

90

86

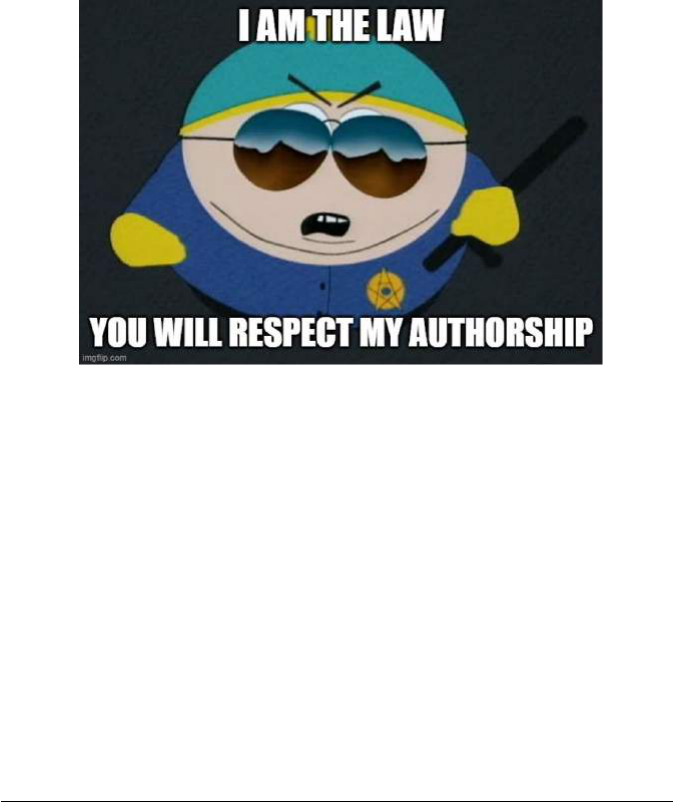

Cartman Respect My Authoritah South Park, Y

OU

T

UBE

, at 0:08 (Oct. 28, 2013),

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XBebjUYItKw [https://perma.cc/HMN5-FJ46]; South

Park, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/subcultures/south-park

[https://perma.cc/CLW7-52SH].

87

17 U.S.C. §§ 201(a)–(b).

88

U.S. C

ONST

. art. I, § 8, cl. 8 (“Congress shall have Power . . . [t]o promote the

Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and

Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”).

89

E.g., M

ARK

R

OSE

, A

UTHORS AND

O

WNERS

: T

HE

I

NVENTION OF

C

OPYRIGHT

8 (1993)

(noting that authors “produce texts through complex processes of adaptation and

transformation”); T

HE

C

ONSTRUCTION OF

A

UTHORSHIP

: T

EXTUAL

A

PPROPRIATION IN

L

AW AND

L

ITERATURE

(Martha Woodmansee & Peter Jaszi eds., 1994) (collection of

papers on the issue of the author’s role in copyright law); Oren Bracha, The Ideology of

Authorship Revisited: Authors, Markets, and Liberal Values in Early American Copyright,

118 Y

ALE

L.J. 186 (2008).

90

Sterk, supra note 13, at 1197–98; accord Bracha, supra note 89, at 265–66.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 13 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 13 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 21 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 473

Others accept the author’s centrality and seek to explain what

should qualify someone as an author. For example, Chris Buccafusco

theorizes that “to be an author of a writing, one must intend to pro-

duce some mental effect in an audience,” leading him to conclude that

garden designers, computer programmers, and others might be

authors.

91

Jane Ginsburg and Luke Budiardjo understand authorship

to be the conjunction of devising a creative plan for a work and physi-

cally executing the work.

92

Right or wrong, the author is copyright law’s central figure. With

these assumptions explored, we now turn to discuss memes.

II

M

EMES

93

In this Part, we introduce the surprisingly elastic and imprecise

definition of the term “meme,” laying bare the centrality of copying to

this category. We then consider the importance of memes by briefly

91

Christopher Buccafusco, A Theory of Copyright Authorship, 102 V

A

. L. R

EV

. 1229,

1232–33 (2016).

92

Jane C. Ginsburg & Luke Ali Budiardjo, Authors and Machines, 34 B

ERKELEY

T

ECH

. L.J. 343, 346 (2019) (applying that concept to assess when the human participants

who interact with artificially intelligent machines might be considered authors).

93

Draw 25, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/draw-25 [https://

perma.cc/7UHU-FUX8].

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 13 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 13 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 22 16-MAY-22 16:37

474 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

exploring their critical role in contemporary creativity, expression,

and political discourse.

A. Overview

94

“Meme” is a remarkably imprecise and elastic term. The scientist

Richard Dawkins coined the word in his influential 1976 book, The

Selfish Gene, to describe a “unit of cultural transmission” that repli-

cates and stays alive by “leaping from brain to brain.”

95

The term’s

origins stem from the conceptual analogy Dawkins drew between cul-

tural and biological evolution; Dawkins chose the word to sound like

“gene.”

96

But Dawkins’s neologism also had a second root that sig-

naled a second conceptual pillar of his theory: the central role of cop-

ying. He chose the term “meme” to reference the Greek word

“mimeme,” meaning “imitation.”

97

Since its invention, the term “meme” has mutated in meaning.

Dawkins used the term broadly to include things that propagate, sur-

vive, and ultimately penetrate cultures, such as “catch-phrases, clothes

94

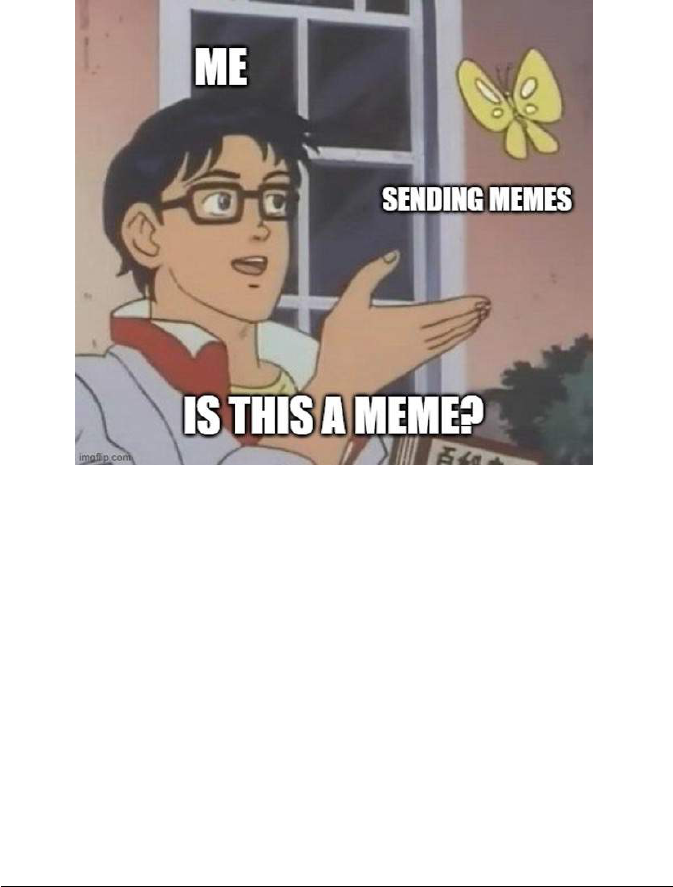

Is This a Pigeon?, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/is-this-a-

pigeon [https://perma.cc/8PBP-424X].

95

R

ICHARD

D

AWKINS

, T

HE

S

ELFISH

G

ENE

249 (Oxford U. Press, Inc. 2016) (1976).

96

Id. Note that there are widespread debates in the field of memetics about this genetic

analogy, including questions it raises about the role of human agency in cultural memes.

See L

IMOR

S

HIFMAN

, M

EMES IN

D

IGITAL

C

ULTURE

10–12 (2013). We return to this debate

below in Section III.H, where we discuss the complexity of authorship in meme culture.

97

D

AWKINS

, supra note 95, at 249.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 14 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 14 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 23 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 475

fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches,” and even the

idea of God.

98

Debates about the definition and nature of memes

have entered multiple disciplines, including psychology, communica-

tions, linguistics, anthropology, and philosophy.

99

Scholars routinely

note the word’s imprecision.

100

The colloquial usage of the term has shifted in the digital era to

become inextricably associated with the internet and digital life.

101

But even in this realm, the word is imprecise. In its broadest contem-

porary usage, “meme” applies to any viral sensation online, such as

trending hashtags or viral videos, or even to viral offline behaviors

that are spread by digital culture. Thus, innocuous (if sometimes non-

sensical) fads, like the plank trend

102

or TikTok dances,

103

have been

called “memes,” as have real-world fashion trends that initially spread

online, such as the alt-right fad of wearing Fred Perry shirts or the

Boogaloo Boys’ wearing of Hawaiian shirts.

104

The term has even pen-

etrated the stock market, where the term “meme stock” refers to

stocks such as GME (Gamestop) that see “sudden and dramatic

surges thanks to social media hype” while at the same time being con-

sidered “merely a joke.”

105

Indeed, some sources use the phrase

“meme culture” as a synonym for internet culture more broadly.

106

98

Id. at 249–50.

99

E.g., S

USAN

B

LACKMORE

, T

HE

M

EME

M

ACHINE

63–66 (1999); D

ANIEL

C. D

ENNETT

,

D

ARWIN

’

S

D

ANGEROUS

I

DEA

: E

VOLUTION AND THE

M

EANINGS OF

L

IFE

339–69 (1995);

K

ATE

D

ISTIN

, T

HE

S

ELFISH

M

EME

: A C

RITICAL

R

EASSESSMENT

(2005). For summaries of

scholarly debates in memetics about the definition and conceptual foundation of memes,

see Thomas F. Cotter, Memes and Copyright, 80 T

UL

. L. R

EV

. 331, 340–47 (2005); David

A. Simon, Culture, Creativity, & Copyright, 29 C

ARDOZO

A

RTS

& E

NT

. L.J. 279, 354–60

(2011).

100

See sources cited supra note 99.

101

See Olivia Solon, Richard Dawkins on the Internet’s Hijacking of the Word ‘Meme,’

W

IRED

UK (June 20, 2013), https://www.wired.co.uk/article/richard-dawkins-memes

[https://perma.cc/64CQ-C5ND]. The term had not yet acquired its present digital valence in

the early days of the internet. Writing in 1998, well before our current meme-driven

culture, Jack Balkin defined memes to include “skills, norms, ideas, beliefs, attitudes,

values, and other forms of information.” J

ACK

M. B

ALKIN

, C

ULTURAL

S

OFTWARE

: A

T

HEORY OF

I

DEOLOGY

43 (1998).

102

See Planking, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/planking

[https://perma.cc/77EZ-ZV4V].

103

See infra Section V.B.

104

See So, White Supremacists Ruined Another Shirt, I

N

S

TYLE

(Sept. 30, 2020), https://

www.instyle.com/fashion/clothing/fred-perry-proud-boys-polo [https://perma.cc/KF3S-

C2BY].

105

Brandon Michael, Top Meme Stocks to Buy Right Now? 5 In Focus,N

ASDAQ

(July 7,

2021), https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/top-meme-stocks-to-buy-right-now-5-in-focus-2021-

07-07 [https://perma.cc/6PLK-BH5Q].

106

See, e.g., Helen Lewis, The Joke’s on Us, A

TLANTIC

(Sept. 30, 2020), https://

www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/09/how-memes-lulz-and-ironic-bigotry-

won-internet/616427 [https://perma.cc/F4TX-T3UT].

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 14 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 14 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 24 16-MAY-22 16:37

476 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

Other sources, however, reserve the word “meme” for a narrower

subset of digital life: digital images that are created and recreated by

continually “pasting captions onto other people’s photos,”

107

by

mixing images together, or by referring, sometimes obliquely, to pre-

vious images.

108

Meme scholar Limor Shifman emphasizes the

intertextual quality of such memes, defining them as “created with

awareness of each other, and . . . circulated, imitated, and/or trans-

formed via the Internet by many users.”

109

Note the visual nature of

memes in this narrower definition. Stacey Lantagne, for example,

describes memes as mutating “visual images that have morphed

beyond their origin to act as their own form of communicative short-

hand.”

110

Typically for digital memes of this sort, the visual image

remains relatively constant, and users change its meaning through new

text or juxtaposition with other images.

111

While we recognize the term’s imprecision, our focus here is on

this narrower subset of memes: viral visual images continually

remixed by multiple users, juxtaposed with text, or mixed with other

images, that ultimately become their own shorthand for meaning.

112

We consider this definition to be the most commonly used meaning of

the term in popular discourse—at least for now. The reader will note

that this Article’s illustrations are all examples of this core meaning of

the term.

Despite the term’s elasticity, one common thread runs through all

the various definitions, including ours: Memes are about copying, on a

large and widespread scale. Dawkins’s reference to “mimeme” or imi-

tation has persisted at the concept’s core. Whatever else a meme is, an

image (or phenomenon) becomes a meme only if it is widely

copied.

113

Thus, as we explore in Part III, the challenge memes pose to

copyright law could not be starker or more fundamental: Copyright

107

See, e.g., Stacey M. Lantagne, Famous on the Internet: The Spectrum of Internet

Memes and the Legal Challenge of Evolving Methods of Communication, 52 U. R

ICH

. L.

R

EV

. 387, 389 (2018); see also David Tan, Digital Memes, Fair Use, and the First

Amendment, J. I

NTERNET

L., May 2021, at 1, 23 (quoting B

RADLEY

E. W

IGGINS

, T

HE

D

ISCURSIVE

P

OWER OF

M

EMES IN

D

IGITAL

C

ULTURE

: I

DEOLOGY

, S

EMIOTICS

,

AND

I

NTERTEXTUALITY

11 (2019)) (noting the “remixed, iterated” nature of digital memes).

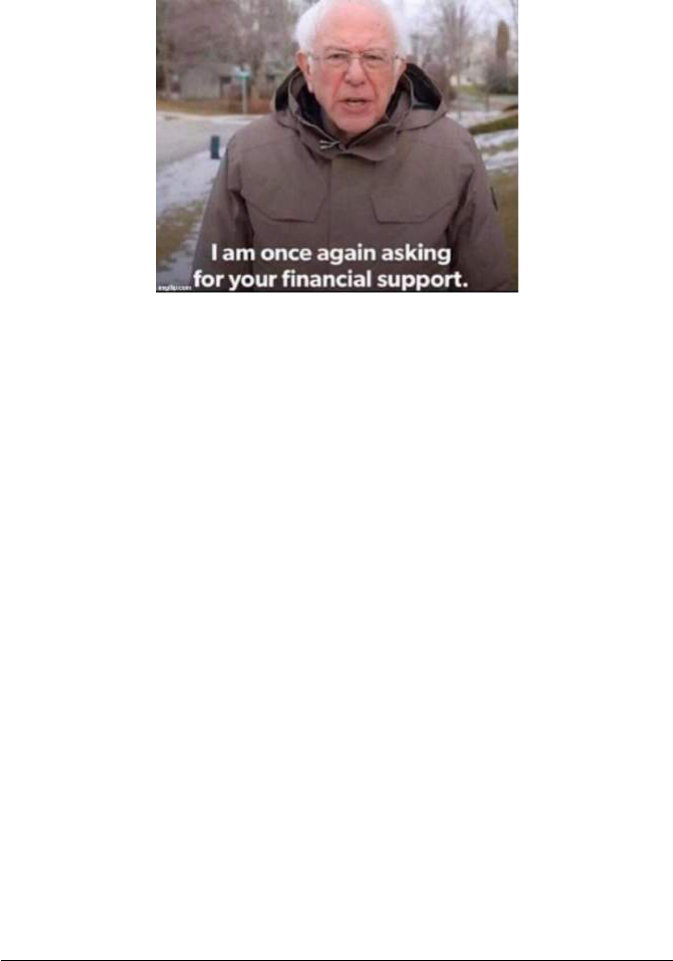

108

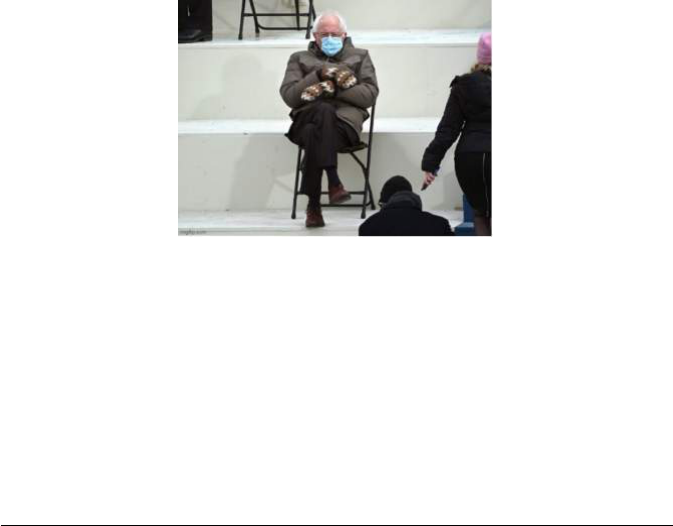

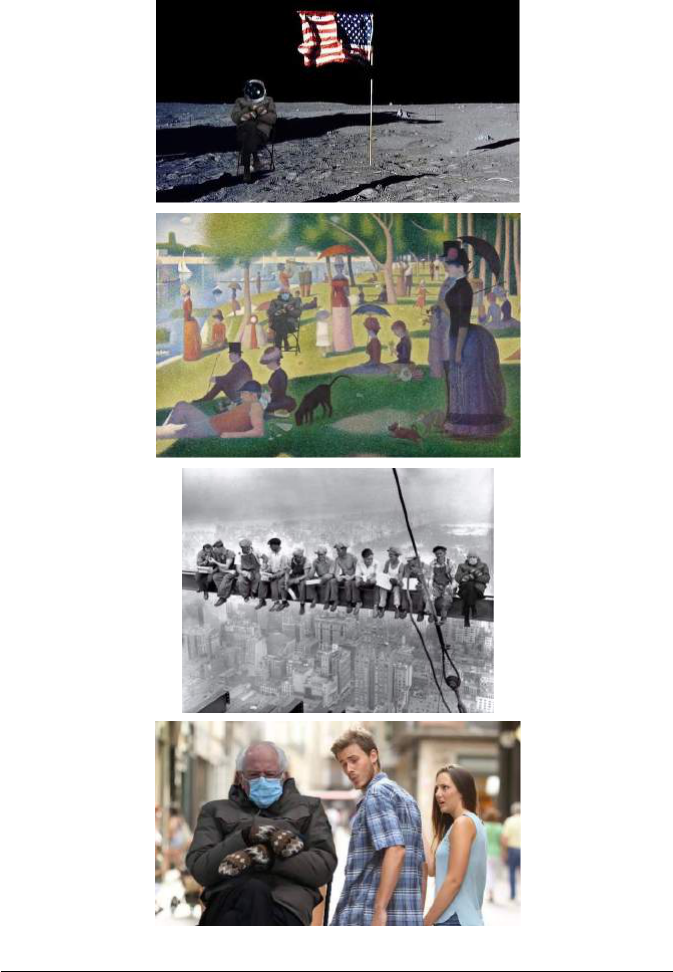

For example, the Bernie Sanders mittens meme that spread like wildfire after the

2021 presidential inauguration typically involved dropping the image of Sanders into new

settings, frequently without text. See infra notes 152–55 and accompanying text and

images.

109

S

HIFMAN

, supra note 96, at 41.

110

Lantagne, supra note 107, at 391.

111

Ronak Patel, First World Problems: A Fair Use Analysis of Internet Memes, 20

UCLA E

NT

. L. R

EV

. 235, 237 (2013).

112

See S

HIFMAN

, supra note 96, at 2–6.

113

See Terrica Carrington, Grumpy Cat or Copy Cat? Memetic Marketing in the Digital

Age, 7 G

EO

. M

ASON

J. I

NT

’

L

C

OM

. L. 139, 153 (2015).

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 15 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 15 Side A 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 25 16-MAY-22 16:37

May 2022] MEMES ON MEMES AND THE NEW CREATIVITY 477

law at its core views unauthorized copying as a threat to creativity. Yet

memes, a paradigm of contemporary creativity,

114

owe their very exis-

tence to limitless, unauthorized, viral copying. These fundamental dif-

ferences lead to numerous disconnects between the use of memes and

traditional copyright law, which we explore in Part III.

B. Why Memes Matter

115

It may be tempting for academics to dismiss meme culture.

116

When you think of the prototypical meme user, you may picture a

Gen-Z teenager in a Reddit chatroom making inconsequential,

puerile jokes about pop culture. And unless you spend your life

online, memes frequently seem impenetrable, their meaning depen-

dent on multiple references to other memes and to (often trivial)

shards of pop culture.

117

Worse, if you invest time trying to puzzle out

a meme’s meaning, by the time you “get it,” it may already be old

news, and so many new ones have sprung up that your time spent

decoding may feel futile.

Despite this, we argue that legal scholars should take memes seri-

ously. Whether viewed from the perspective of copyright law (the

focus here), which values creativity, or First Amendment law, which

prizes a robust marketplace of ideas and political discourse, memes

114

See infra Section II.B.

115

Tuxedo Winnie the Pooh, K

NOW

Y

OUR

M

EME

, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/

tuxedo-winnie-the-pooh [https://perma.cc/57BP-8939].

116

See S

HIFMAN

, supra note 96, at 2 (noting that the meme concept “has been the

subject of constant academic debate, derision, and even outright dismissal.”).

117

For discussion of the lo-fi aesthetic and the absurdist, ironic tone of meme culture, as

well as its origins on 4chan and later Reddit and Tumblr, see Lewis, supra note 106.

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 15 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

44159-nyu_97-2 Sheet No. 15 Side B 05/17/2022 12:35:30

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\97-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 26 16-MAY-22 16:37

478 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:453

matter. We view them as a paradigm of contemporary creativity and a

powerful form of contemporary speech, often with significant political

consequences.

118

We see memes as paradigmatic of contemporary cultural expres-

sion because of the fundamental role copying plays in their production

(going back to the “mimeme” root of the word). As we have previ-

ously argued, while “creativity has always relied to some extent on

copying, the role of copying has taken on much greater urgency in our

contemporary digital culture.”

119

Thus, scholar Limor Shifman writes

that the “the meme concept encapsulates some of the most funda-

mental aspects of contemporary digital culture.”

120

A second aspect of memes also makes them paradigmatic for us:

They are primarily visual in nature. In most memes (but not all), an

image stays constant as the shortcut for meaning, but users continually

swap in new text. This reliance on the visual image also makes memes

emblematic of a larger shift through which “the image has surpassed

the word as the dominant mode of communication,” as one of us has

previously argued.

121

Indeed, Martin Gurri has observed of digital cul-

ture: “What is usually referred to as new media really means the tri-

umph of the image over the printed word.”

122

Moreover, memes matter because they are wildly popular and

one of the most commonly created, shared, and consumed types of

expression. As Fortune put it in 2016, “[f]or the first time ever, memes

are more popular than Jesus,” as “memes” became the most popular

Google search, beating “Jesus”—the most popular search term since

118

See, e.g., Joan Donovan, How Memes Got Weaponized: A Short History, MIT T

ECH

.

R

EV

. (Oct. 24, 2019), https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/10/24/132228/political-war-

memes-disinformation [https://perma.cc/F6DP-5FZ7] (noting the use of memes to create

misinformation both by domestic political activists and foreign operatives); Douglas

Haddow, Meme Warfare: How the Power of Mass Replication Has Poisoned the US

Election,G

UARDIAN

(Nov. 4, 2016), https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/04/

political-memes-2016-election-hillary-clinton-donald-trump [https://perma.cc/7AM6-9637]

(“[M]emes are ruining democracy.”); Kaitlyn Tiffany, The Story of the Internet, as Told by

Know Your Meme, V

ERGE

(Mar. 6, 2018), https://www.theverge.com/2018/3/6/17044344/

know-your-meme-10-year-anniversary-brad-kim-interview [https://perma.cc/TE8H-FMHP]

(quoting a technology journalist who describes Donald Trump as a “meme president” and

discusses the power of memes in “shaping public opinion”).

119

Adler & Fromer, supra note 47, at 1529.

120

S

HIFMAN

, supra note 96, at 4.

121

Amy Adler, The First Amendment and the Second Commandment, 57 N.Y.L. S

CH

. L.

R

EV

. 41, 42 (2013) [hereinafter Adler, First Amendment]; see also id. at 42–45 (discussing

how images have the power, unlike text, to be equated with what they represent, and

comparing the contemporary fascination with visual media to a “bewitching pull of

images” felt in ancient times).

122

M

ARTIN

G

URRI

, T

HE

R

EVOLT OF THE

P

UBLIC AND THE

C

RISIS OF

A

UTHORITY IN