2 02 1

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

2

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

JOHN RUCYNSKI, JR. AND CALEB PRICHARD

Japan

Implementing Humor

Instruction into English

Language Teaching

I

n my first year teaching English at a university in Japan, I (John)

wanted to give my students something different for a Friday lesson:

sharing one of my favorite episodes of the American television

show The Simpsons. I selected about ten of the funniest jokes from

the episode and envisioned jealous colleagues curious about the

enthusiastic laughter coming from my classroom. Unfortunately,

instead, my silent classroom probably made them wonder if I had given

a test that day.

Why were The Simpsons jokes met with such

silence? From a cultural perspective, humor

may be a universal feature of all cultures,

but what is considered funny varies greatly

from culture to culture. From a language-

teaching perspective, at least three key

mistakes prevented the lesson from being a

successful integration of humor and language

teaching. First, not enough scaffolding was

done. I mistakenly assumed that my Japanese

students would be familiar with the show

and its style of humor. Second, there was no

connection between that particular episode

and the class content. In other words, there

was no goal of the lesson, other than merely

wanting the students to appreciate American

humor. Third, there were no opportunities

for students to engage with the humor. It was

a failed humor lesson of the teacher merely

trying (more and more desperately) to explain

why something was funny.

One reason we share this anecdote is that it

reflects why some teachers avoid including

humor in the English language classroom.

They claim that humor is simply too complex

and will merely cause confusion. By writing

this article, however, we argue that the

benefits of implementing humor instruction

in the English teaching curriculum far

outweigh the disadvantages or difficulties.

Considering this, I (John again) did not

abandon The Simpsons or other forms of humor

as part of English instruction. Rather, I made

clips from the show part of a thematic unit on

humor and American social issues (Rucynski

2011), but I greatly adapted my teaching

approach, based on ideas described later in

this article.

A farewell message I received from one of the

students in the course two years later, when

the student was graduating from university,

perhaps best encapsulates why I attempted to

use humor in my teaching in the first place.

The student wrote, “After your class, I went

on to watch almost every Simpsons episode.

It kept me motivated to study English and

helped me to communicate with Americans

when I studied abroad. My goal is to someday

2021

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

3

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

watch these episodes without subtitles.” In this

article, we will discuss the why and the (much

more complex) how of implementing a focus

on humor into English language teaching.

WHY INCLUDE HUMOR INSTRUCTION?

There is a common misconception that

including humor in language teaching is

merely a fun or frivolous element that is used

to occasionally spice up classes. While humor

does indeed have the power to make learning

more fun and memorable, it can also serve a

much deeper purpose in language education.

A lack of understanding of the humor of the

target culture can cause embarrassment or

isolation for learners (Lems 2013). Learners

are likely to encounter humor in conversations

in the second language (L2) but suffer from

anxiety about how to actively engage with the

humor (Shively 2018). Helping our students

become more familiar with the humor of

English-speaking cultures thus empowers

them by improving their intercultural

communicative competence, as humor is

a great way to bond with target-language

speakers (Rucynski and Prichard 2020).

As John’s former student wrote, familiarity

with The Simpsons, as just one example of

American humor, helped him to communicate

with American people.

L2 humor competence is an integral

component of becoming proficient in a

foreign language. This involves not merely

appreciating the humor of foreign cultures,

but also understanding how it is used. The

timing, frequency, and purpose of humor

greatly vary from culture to culture. When

people use humor, there is often incongruity

between the literal and intended meanings

of their words. English language learners

with a high level of humor competency have

the ability to decode the message and to

identify the true purpose of the humor

(e.g., just making a joke, criticizing a person

or situation).

On a related note, acquiring humor

competency in a foreign language also helps

learners develop critical-thinking skills.

English language learners will encounter

a great amount of humor as they navigate

the Internet and social media platforms.

The ability to decipher the meaning of

political memes and distinguish satirical news

items from real news items is an essential

component of the increasingly important

twenty-first-century skills of digital and

media literacy.

HOW TO IMPLEMENT HUMOR

INSTRUCTION INTO LANGUAGE

TEACHING

The first step in the process is determining

the purpose of including humor. Is the goal

to teach with humor or teach about humor?

While the two goals often overlap, we refer

to teaching with humor as the teacher using

any humorous techniques (e.g., giving funny

examples, telling humorous anecdotes) to

improve the atmosphere of the class and

make language learning more enjoyable and

memorable. On the other hand, teaching

about humor (the focus of this article) refers

to helping learners improve their competency

with humor of the target culture(s). An

increasing amount of research has focused

on teaching about humor in the context of

language teaching. Research ranges from

humor competency training on specific types

of humor—including jokes (Pimenova 2020),

satirical news (Prichard and Rucynski 2019),

and sarcasm (Kim and Lantolf 2018; Prichard

and Rucynski 2020)—to developing extensive

taxonomies of microskills to help learners

better understand L2 humor (Wulf 2010).

Teaching about humor, however, certainly

does not entail the teacher giving dry

academic lectures about the humor customs

of different cultures. Humor instruction can

be implemented by using practical, engaging,

and interactive learner-centered activities.

Still, it is vital to establish the purpose and

goals for introducing humor. As explained in

the introduction, humor instruction should

have a strong connection with the course

curriculum. Bell and Pomerantz (2016)

propose a backward design model when

teaching learners about humor. In other

2 02 1

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

4

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

The cultural background, proficiency level, and needs of

your learners should greatly inform what aspect of humor

instruction you implement into the curriculum.

words, just like the teaching of any language

point, teaching about humor requires

identifying the target results. Why does the

teacher believe it is important for learners to

understand this aspect of humor, and what are

the best techniques for teaching it as part of

the curriculum?

Bell and Pomerantz (2016, 170) also suggest

four possible results of humor instruction:

1. Identication. Learners detect that humor

is being used.

2. Comprehension. Learners are able to

understand the intended meaning of the

humor.

3. Response. Learners are able to properly

react to the humor, such as commenting

on the funniness (or “unfunniness”!) of

the humor or replying with their own

humor.

4. Production. Learners actually create their

own humor.

Bell and Pomerantz (2016) further stress the

importance of researching respective forms

of humor. Just as a language teacher needs

extensive knowledge of a grammar point in

order to teach it, teachers who aim to provide

instruction on a respective form of humor

need to ask, “What linguistic structures,

lexical items, and cultural understanding will

learners need to achieve the desired results?”

(Bell and Pomerantz 2016, 179).

Instruction on respective forms of humor

does not always need to include a focus on all

four desired results. For example, the ability

to identify and comprehend English satirical

news can help English language learners to

improve their digital and media literacy, but

not many teachers would task learners with

producing their own satirical news. While

humor production in the L2 can be a creative

and fun challenge for learners, Bell and

Pomerantz (2016) stress that the end goal of

humor instruction is not to produce “funny

students,” but “to familiarize learners with

a variety of conventional practices around

humorous interaction, so that they are better

able to take part in it” (170).

A FRAMEWORK FOR INCLUDING HUMOR

INSTRUCTION IN LANGUAGE TEACHING

Despite these clear potential goals of humor

instruction outlined by Bell and Pomerantz

(2016), it still can be difficult to imagine

how to realize these goals from a practical

standpoint. Teachers need to carefully consider

which aspects of humor to include in language

instruction, what kinds of activities and

resources can best facilitate this instruction,

and which of the four aforementioned

results should be the focus (Rucynski and

Prichard 2020). The teaching context is

vital when considering humor instruction.

In other words, the cultural background,

proficiency level, and needs of your learners

should greatly inform what aspect of

humor instruction you implement into the

curriculum. As an example, attempting to

teach sarcasm to a group of absolute beginners

would make little pedagogical sense. On

the other hand, we often include a unit on

sarcasm for our Japanese students who are

preparing to study abroad, as they are likely

to encounter this form of humor in English-

speaking countries, and previous students have

expressed confusion about it. It is important

to help learners fill in the gaps in their humor

competence.

We will now take a deeper look at three

specific types of humor by explaining the

2021

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

5

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

rationale for including a focus on each type

and providing possible activities and resources

for the relevant potential results of humor

instruction. In addition, we will provide

suggestions for modifying the instruction for

learners of different proficiency levels. While

there are countless types of humor to choose

from, the forms of humor we will focus on

in this article are verbal irony, memes, and

satirical news. Teachers should consider their

own teaching context when deciding which

forms of humor to include; they should be

able to answer “Yes” to the following three

questions before making a respective type of

humor a part of their humor instruction:

1. Are learners likely to encounter this

form of humor when communicating

(either face-to-face or online) in the

target language?

2. Is this form of humor likely to be

challenging for students to understand

(e.g., because of a relative lack of the

same humor in their native culture)?

3. Does instruction on this form of humor

provide value beyond just humor (e.g.,

insights into the target culture)?

HUMOR INSTRUCTION FOR VERBAL

IRONY

Rationale

In the context of English language teaching,

learners would greatly benefit from a deeper

understanding of verbal irony, including

sarcasm (Prichard and Rucynski 2020).

Learning a language requires much more than

just memorizing vocabulary and grammar

rules, as learners also need to differentiate

between an interlocutor’s actual words

and intended meaning. This is no easy task,

especially for learners who come from

cultures with a relative lack of sarcasm.

We were reminded of this several years ago

when we were visiting the United States

and boarded a long-distance bus. Just before

departing, the driver looked back to see

that the bus was only at about ten percent

capacity and shouted out in a straight voice,

“No fighting over the seats!” In moments like

this, we often put ourselves in the shoes of our

current Japanese university students. A great

majority of our students would understand

every English word in that sentence, but

may be perplexed by the intended meaning,

considering that sarcasm is relatively rare in

Japan and it is also uncommon to make such a

joke with complete strangers.

Failure to detect or understand sarcasm can

quickly lead to confusion or embarrassment.

However, sarcasm remains a ubiquitous

feature of conversation in English-speaking

countries. Some may argue that sarcasm

is merely a negative form of humor that is

best avoided in the context of the language

classroom, but it is more complex than that,

as verbal irony can include both sarcasm

(positive language with negative intent) and

jocularity (negative language with positive

intent) (Rothermich and Pell 2015). So,

without a proper understanding of verbal

irony, an English learner could easily be

confused by sarcasm, such as being told,

“Nice job!” when making a mistake. They

could also be hurt by well-intentioned

jocularity, such as if they humbly say, “Sorry,

I’m not a good cook,” after preparing a

delicious meal and being told, “Oh yeah,

you’re such a terrible cook!”

Identifying sarcasm

Before teaching students the strategies for

identifying sarcasm, teachers can show simple

literal and nonliteral examples. In pairs or

groups, learners can try to induce which ones

are sarcastic, and they can try to identify cues

they notice or share other cues that they know

(Prichard and Rucynski 2020).

The teacher can then highlight the various

verbal and nonverbal cues that learners

could not identify on their own. Vocal cues

(prosody) include exaggerated stress or

intonation, elongated syllables, a monotonous

tone, and slower speech. Visual cues include a

blank face, averted gaze, glaring, and winking

(Rothermich and Pell 2015). Teachers may

make use of a range of visuals and audio

or video resources to demonstrate these

2 02 1

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

6

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

cues without needing to rely on technical

terminology. We highly recommend

introducing sarcasm not with fast-paced

scenes from movies or TV shows, but instead

with examples that are easier to understand,

especially in the initial recognition stage.

Proper scaffolding with numerous examples

helps prevent the humor-instruction failure

described at the beginning of this article.

Teachers can also demonstrate verbal cues for

the class. To make the instruction interactive,

teachers make two similar statements, one

sincere and one sarcastic. The class then

attempts to identify the sarcastic remark.

One example John uses with his class is the

following:

Statement #1: I love baseball. It’s so

exciting.

Statement #2: I love soccer. It’s sooooo

exciting.

The learners guess alone, then discuss their

answers with a partner or group. They can also

share which cues they identified. The teacher

then goes over the answer. (The elongated

stress in the second statement reveals that

John finds soccer to be boring and prefers

baseball.)

Teachers could also demonstrate visual

cues, but a plethora of online examples are

accessible. A search for “sarcastic expression”

on Google Images will provide hundreds of

examples. Again, to make the lesson more

interactive and engaging, the teacher could

provide images of several different faces and

task learners with identifying the ones that are

most likely to express sarcasm.

For learners less familiar with sarcasm,

teachers can provide written dialogues to help

train learners to identify illogical statements

that do not fit the context. One example is

the following:

A: How’s your day going?

B: Not bad. And you?

A: I failed my math test, my girlfriend

broke up with me, and then I got

stuck in the rainstorm without an

umbrella.

B: It sounds like you’re having a

wonderful day!

The final line by Speaker B should easily be

identifiable as a sarcastic statement.

In addition to identifying the sarcastic

statement, learners could be given two short,

similar dialogues and asked to identify the one

that includes sarcasm.

Dialogue #1:

A: Do you like your new teacher?

B: He gives a lot of homework, never

smiles, and doesn’t remember my

name. Yes, I love my new teacher.

Dialogue #2:

A: Do you like your new teacher?

B: She has an exciting teaching style,

and the class time always goes by very

fast. Yes, I love my new teacher.

Again, this could be a collaborative task

with the purpose of developing

competence. The teacher can guide

learners, as needed. (The incongruity in

Dialogue #1 could help learners to identify

its sarcasm.)

Comprehending sarcasm

We may assume that if a speaker is being

sarcastic, then the true meaning is just the

opposite of what was said, but this is not

always the case. The literal meaning may be

simply an exaggeration or understatement

of the speaker’s true meaning. Moreover,

students should understand the various

implications and roles of sarcasm, which could

be to amuse, to lighten criticism, to bond

with a peer, or to achieve some other purpose

(Prichard and Rucynski 2020).

2021

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

7

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

The teacher can give the learners several

examples, and students, working in pairs or

groups, discuss the speaker’s true meaning.

For example, for the following dialogue,

they may discuss whether Speaker B liked the

movie and the reason.

A: Did you like the movie I suggested?

B: I slept through half of it. I just love

three-hour movies … ! Next time,

you should invite me to a four-hour

movie. Ha ha. (smiling)

Students may deduce that Speaker B didn’t

enjoy the movie because it was too long. They

then brainstorm the purpose of the sarcasm

(perhaps to lighten the mood despite the

criticism). The teacher can help point out cues

the students could not recognize.

Responding to sarcasm

Training learners to respond to sarcasm

is complicated, as sarcasm can be a rather

negative form of humor. Sarcasm, however,

takes many forms and is not always used

to criticize the interlocutor, but rather

another target. So the speaker may merely

be expecting agreement. When it comes

to jocularity, the speaker may actually be

complimenting the interlocutor, but by using

negative words with positive intent.

It is best for the teacher to advise learners

that they should not feel forced to agree with

sarcasm when it is political or biting, but that

with more casual topics, people tend to play

along with sarcasm as a conversational norm

(Colston 2017). For example, a common

conversation starter in England is the sarcastic

statement, “Lovely weather we’re having.”

If the interlocutor takes such a greeting

literally, they might be tempted to reply with

something like, “Actually, I don’t like the rain.”

The social expectation, however, is to simply

agree with a similarly sarcastic response such

as, “Yes, lovely, isn’t it?”

Learners should also be informed, however,

that when they get to know someone well, it

is perfectly natural to either play along with

or disagree with sarcastic statements. One

way to practice this would be for the teacher

to make an obviously sarcastic statement

and ask learners to state their agreement or

disagreement with the intended meaning.

Learners could be given a range of responses

for either category, as shown in Table 1.

Producing sarcasm

Some teachers may question whether they

want to teach their students how to be

sarcastic. However, practicing sarcastic and

sincere statements can reinforce the sarcasm

cues introduced by the teacher while

making the class more engaging. A simple way

to do this is to ask each student to prepare a

pair of statements that include one sincere and

one sarcastic utterance (similar to the popular

“Two Truths and a Lie” icebreaker). Students

should start with conversational topics that

they have a common understanding about,

such as sports, musicians, or actors. As with

our previous example, students could say

they like two sports (or two musicians, etc.),

and their group members need to guess the

sincere and sarcastic statements. To add to the

activity, students could be tasked with using a

different cue each time (e.g., a verbal cue such

as exaggerated intonation for one statement

and a visual cue like eye rolling for another).

However, the teacher should warn the

class about the risks of having their sarcasm

misunderstood.

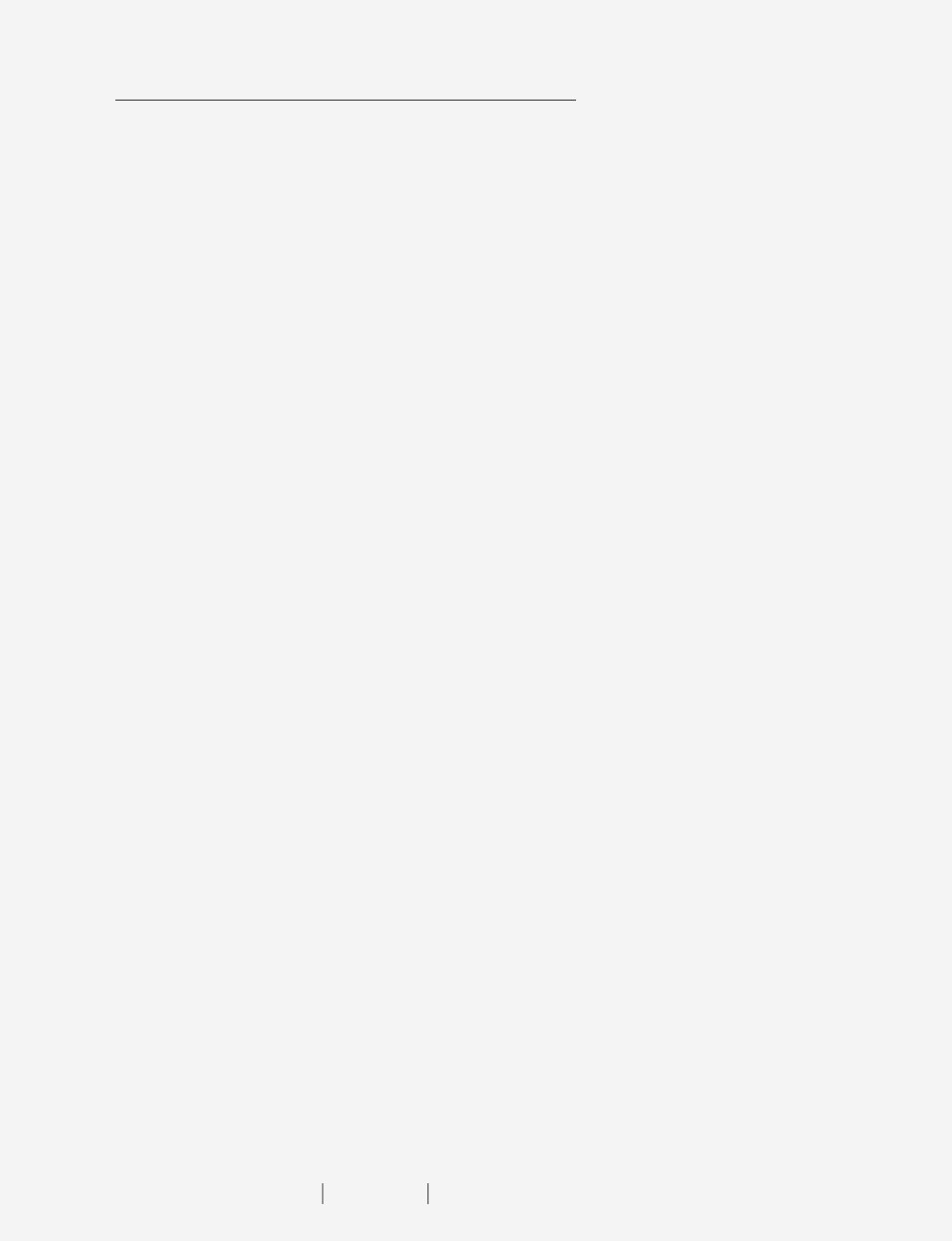

Sarcastic statement (teacher) Responses for agreeing Responses for disagreeing

I just love watching soccer. It’s

sooooo exciting.

• I’m not into soccer, either.

• Yeah, soccer is boring, isn’t it?

• Yeah, I’d rather watch

________.

• Hey, soccer is exciting!

• Actually, I love watching

soccer.

• Are you being sarcastic?

Soccer is a great sport!

Table 1. Examples of responses for agreeing or disagreeing with a sarcastic statement

2 02 1

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

8

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

Suggestions for dierent prociency levels

For lower-proficiency learners, teachers can

provide much more visual support to show

contextual cues clearly. For example, show

a picture of a rainstorm or blizzard with

the statement, “Lovely weather, isn’t it?”

to illustrate that verbal irony expresses the

opposite of the true intention or reality. In

addition, students do not need to be taught the

technical vocabulary for visual cues of sarcasm

(e.g., blank face, averted gaze), as these can

easily be demonstrated. Finally, the teacher can

provide transcripts for any practice dialogues

to ensure that learners catch and understand

all the necessary vocabulary.

While more-proficient learners will also

benefit from an overview of visual cues, the

teacher can give authentic examples with

verbal cues and vocabulary that are more

sophisticated. The teacher can also provide

examples showing how sarcasm is used for

serious topics. For example, speakers often

use sarcasm to criticize political figures or

comment on social issues.

HUMOR INSTRUCTION FOR MEMES

Rationale

Social-media platforms such as Facebook and

Twitter provide English language learners the

opportunity to interact in English with millions

of people around the world. Memes rapidly

spread with the progression of the Internet and

are now a ubiquitous feature of social media.

Image macros, a popular form of memes, are

easily recognizable by their template of a single

image with text in all caps above and below

the image. Image macros can range from funny

comments about trivial daily events to biting

criticism about social issues or political figures.

English language learners benefit from a

deeper understanding of English memes for

several reasons. First, social media offers

free opportunities for English learners, and

they will certainly encounter memes if they

use social media in English. Improving their

ability to comprehend and respond to memes

can make learners more active and confident

social-media users. Second, memes generally

offer short messages, giving students the

opportunity to learn vocabulary and English

expressions in context. In addition, memes

offer insights into English-speaking cultures,

as they often feature images of famous

figures, ranging from sports figures (LeBron

James) to movie characters (Willy Wonka)

and even to Muppets (Kermit the Frog).

Finally, familiarity with memes can deepen

understanding of how humor is used in

different cultures, as memes are often used as

commentary on social issues.

Identifying and comprehending memes

For this form of humor, the stages of

identification and comprehension can be

combined. After all, students should be able

to instantly recognize a meme, but the bigger

challenge is to identify the different common

memes and comprehend the set message

conveyed by different established memes. As

suggested by Henderson (2017) and Ohashi

(2017), a good starting point for identifying

and comprehending memes is to familiarize

learners with some of the most well-known

examples of English memes, making use of the

popular image-macro type of meme.

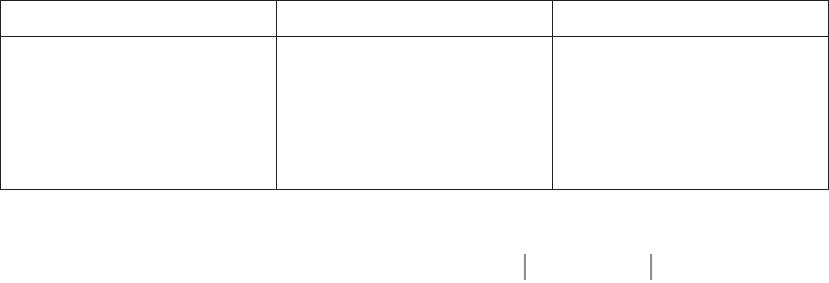

Match the Meme Character in Column 1 With the Text in Column 2

Bad Luck Brian

1. YOU LOOK HAPPY

STOP IT

Grumpy Cat 2. LATE TO WORK

BOSS WAS EVEN LATER

Success Kid 3. FINDS WATER IN THE DESERT

DROWNS

Table 2. Matching activity using popular image-macro memes

The answers are Bad Luck Brian (3), Grumpy Cat (1), and Success Kid (2).

2021

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

9

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

Teachers should select the memes that they

feel would be most comprehensible and

interesting for their learners, but three

examples to start with could be the famous

meme characters Bad Luck Brian (an awkward

teenager whose unlucky experiences are the

punch line), Grumpy Cat (an angry-looking

feline that shows displeasure with everything),

and Success Kid (a child grasping his fist to

show his pleasure at a small victory). To help

learners become familiar with the pattern

of each meme, teachers can ask learners

to match the character with a sample text

(Henderson 2017). The text should be

displayed to indicate the top and bottom

sections of each meme. See Table 2 for an

example. (At this stage, learners can be

allowed to check their dictionaries for any

unknown vocabulary.)

To help students improve their ability to

understand English punch lines, teachers

can task students with matching the top and

bottom captions for the same meme character

(Ohashi 2017). Again, learners can use their

dictionaries at this stage, if necessary. See

Table 3 for an example using Success Kid.

Responding to memes

Compared to sarcasm, responding to memes

should be an easier challenge for language

learners, considering that they are a written

form of humor shared on social media, giving

learners more time to process the humor

than the natural speed and randomness with

which sarcasm is used in conversation. One

safe and interactive way to have learners

practice responding to memes is to create

a class-only online site or make use of a

learning management system (LMS). An LMS

restricted to only students and the teacher is

also a safe place for learners to share memes

they find and like and express confusion or

ask for clarification if they do not understand

certain memes. Learners could be tasked with

responding to their classmates’ shared memes

and asking for clarification, as in Table 4.

Producing memes

Memes also provide a safe and friendly format

for learners to practice producing their own

humor. Many people make their own memes,

and English language learners can certainly do

the same, with enough support and training.

There are free websites where students can

easily learn to create their own memes and

share them with classmates (see, for example,

https://imgflip.com/memegenerator and

https://makeameme.org/).

Activities can progress from more restricted

(all class members creating a meme based

on a well-known meme character or two)

to more open. Humor instruction is most

effective when the humor is not merely

humor for the sake of humor, but when it

complements or expands on other aspects

of the language-learning curriculum. If the

teacher gives students a writing assignment

about a happy or lucky experience, creating

a meme using Success Kid is a fun way for

learners to visualize and share the contents

of their writing. Additionally, writing

about an unlucky experience could be

complemented by an original Bad Luck

Brian meme, and an activity about pet

peeves could be expanded with a Grumpy

Cat meme.

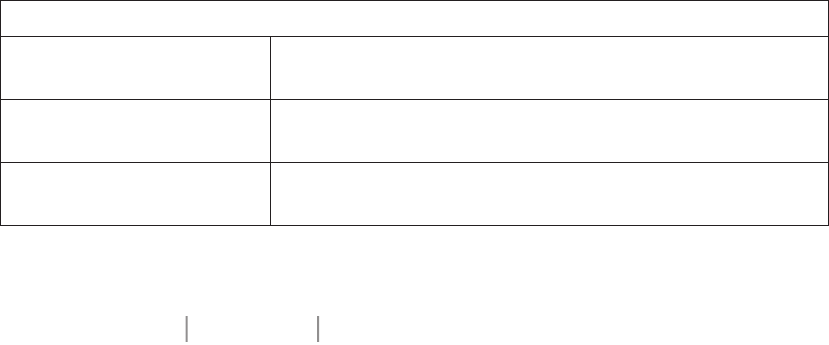

Match the Top Text in Column 1 With the Bottom Text in Column 2

1. PUT CANDY BAR IN SHOPPING CART A. DIDN’T GET SAUCE ON IT

2. ATE SPAGHETTI WHILE WEARING A

WHITE SHIRT

B. GOT INVITED OUT TO DINNER

3. FORGOT TO GO GROCERY SHOPPING C. WITHOUT MOM NOTICING

Table 3. Example of Success Kid activity matching top and bottom text

The answers are 1/C (children often plead with their parents to buy them candy while grocery

shopping); 2/A (we often unluckily spill food on our clothes when we are wearing white); and

3/B (this describes the feeling of something lucky happening after we make a mistake).

2 02 1

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

10

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

Suggestions for dierent prociency levels

Of the three types of humor explored in this

article, memes are likely the most accessible

for lower-proficiency learners, as they include

visual support (the main image), employ

short messages (only two lines of text), and

often feature repetition (famous characters

that are always used to convey similar

messages). As a result, most of the activities

described in this section should be appropriate

for lower-level learners.

For more-proficient learners, the teacher

can introduce memes that illustrate messages

that are more complex than those conveyed

through famous characters such as Success

Kid. For example, another famous meme

character is Condescending Wonka. These

memes depict a screen capture of Gene

Wilder in the movie Willy Wonka & the

Chocolate Factory and feature heavily sarcastic

messages. The teacher could also introduce

political memes, especially during an election

cycle, to help learners raise their awareness

about how humor is used to comment on

social issues in English-speaking countries.

HUMOR INSTRUCTION FOR ONLINE

SATIRICAL NEWS

Rationale

Satirical news can refer to either satirical

TV news programs such as The Daily Show or

satirical digital media such as The Onion. In this

article, we will focus on the latter format, as we

find it to be a more accessible form of humor

for English language learners. Online satirical

news is another ubiquitous feature of social

media in the English-speaking world. Satirical

news mimics real news to mock or satirize

everything from trivial daily matters (e.g.,

shopping manners) to serious social issues (e.g.,

politics and elections). The Onion, published

in the United States, is now arguably the most

famous satirical news site in the world, with

over 6.3 million likes on Facebook. This form

of humor is also common in other English-

speaking countries, with popular examples

including The Daily Mash (U.K.), The Beaverton

(Canada), and The Shovel (Australia).

English language learners can benefit from

exposure to online satirical news. One reason

is that they are likely to encounter satirical

news on social media, but they may mistake

it for real news if they are not familiar with

this type of humor. Again, it is important to

use types of humor that are challenging (for

linguistic or cultural reasons) for students

to understand, but then provide humor

instruction to make this type of humor more

accessible. Mistaking satirical news for real

news can cause confusion or embarrassment

for learners. Another reason is that the ability

to recognize different forms of news (e.g.,

satirical news, fake news) is an increasingly

important part of the twenty-first-century

skills of digital and media literacy. Finally,

as with other forms of humor, exposure to

satirical news provides cultural insights into

English-speaking countries. Learners can

improve their understanding of important

figures and events and see how humor is

sometimes used as social criticism.

Identifying satirical news

Satirical news items can be tricky to

recognize, as they are designed to mimic the

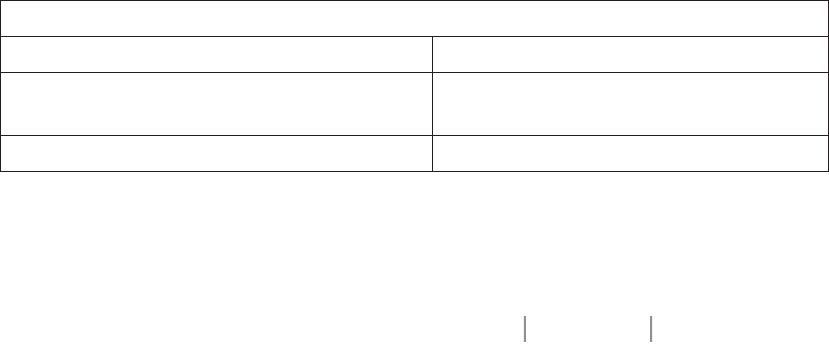

Expressions for Liking a Meme Expressions Asking for Clarification

That’s a good one! What does ________ mean?

It took me a while, but now I get it! I’m not sure I get this one. Why is it funny?

That’s (funny / hilarious / hysterical)! I don’t get it. Can you explain what the joke is?

I know how (he /she) feels! Does this mean that ________?

HAHA / HEHE / LOL / ROTFL Is this funny because ________?

Table 4. Expressions for liking a meme and asking for clarication

2021

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

11

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

appearance of real news. We will introduce

two possible approaches to training English

language learners to recognize satirical news,

one involving stylistic cues and one involving

critical-reading and critical-thinking skills.

Although satirical news does mimic real news,

cues about the appearance and writing style

can also help learners to distinguish between

satirical and real news. One hint is in the

headline. Many satirical news sites might use

particularly large font sizes and capitalize

all words in the headlines (even articles and

prepositions), giving a more tabloid-like

appearance. Other stylistic hints include

casual headlines (e.g., using slang expressions

that might not be used in headlines of real

news) or vague details (e.g., referring to a

“local man” rather than using a name).

As mentioned, the ability to recognize

different forms of media is an important

aspect of digital and media literacy. A second

approach to helping learners recognize

satirical news is to focus on the content of the

articles and use critical-reading and critical-

thinking skills to determine whether the

respective stories could be real news. Several

cues could be part of training to assist learners

in improving their ability to detect satire.

As a starting point, learners can consider

the following two questions when trying to

recognize different forms of media:

1. Is the article newsworthy?

2. Is the article believable?

About the first question, consider a sample

headline from The Onion: “Grandfather A

Man Of Few Shirts.” Would a story about a

grandfather’s wardrobe really make the news?

To address the second question, learners

can be informed that one device used by

satirical news writers is to put famous

figures in absurd or incongruous situations.

For example, a headline from Onion Gamers

Network (a section of The Onion devoted to

video games) in 2020 read, “While Abraham

Lincoln Was Great In Many Ways, We At

OGN Must Examine His Troubling Legacy Of

Never Playing Video Games.” It is an obviously

absurd and unbelievable headline, considering

that Lincoln was president of the United

States roughly 100 years before the first video

game was even created!

One activity we have used in our English

reading courses is to design practice tests that

include a mixture of satirical news items and

offbeat but true news items. The teacher can

provide a mix of items with just the headline

and a blurb from each article. Just providing

a segment of the articles is sufficient, for two

reasons. First, this mimics how satirical news

items appear on social media. Second, readers

can usually identify satirical news from just

the headline or the first line or two of an

article. For example, two of the following

articles are offbeat but true news items, while

two are from satirical sources:

1. Bear necessities? Furry visitor on the

prowl in California store

2. World’s scientists admit they just don’t

like mice

3. ‘UFO’ in Congo jungle turns out to be

Internet balloon

4. Study reveals: Babies are stupid

Using the previous two critical-thinking

prompts, learners can hopefully identify that

number two and number four come from

satirical news. (Both satirical items are from

The Onion, while the true stories come from

the “Oddly Enough” section of Reuters.) Hints

that could be used to identify the different

forms of news include the following:

• #1 is believable, as there are often news

stories about wildlife encroaching on

human communities.

• #2 would be absurd, as professional

scientists would not state that they do not

like rodents.

• #3 is also believable, as it is common for

UFO sightings to later be followed by a

rational explanation.

2 02 1

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

12

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

• #4 is also absurd. In addition, a slang

or offensive term like “stupid” is not

commonly used in real news articles.

Comprehending satirical news

While teachers can provide learners with cues

to help them recognize satirical news with

some practice, actually comprehending the

humor is a more challenging task. In addition

to common English challenges like vocabulary,

understanding satirical news often requires a

high degree of cultural literacy and awareness

of current events. Still, this should be seen as

a worthwhile challenge. Examining the humor

of a culture can also lead to a deeper awareness

of and interest in politics and social issues. This

is also an example of how humor instruction

can have value beyond just the humor.

Exposure to politics or social issues through

satirical news leads to increased background

knowledge and empowers English language

learners to improve digital and media literacy.

Increasing comprehension of English

satirical news can be promoted by classroom

collaboration, both student-to-student

and student-to-teacher. For example, the

teacher can provide learners with a selection

of satirical news headlines and task them

with writing an explanation of the meaning.

In other words, what is the article really

expressing? Who or what is the target of

the humor? In the safe environment of the

language classroom, learners can enjoy the

process of comparing ideas and answers until

the teacher offers a final explanation. This

process could start with teacher-selected

articles and progress to students selecting

their own articles from a range of satirical

sites suggested by the teacher. One out-

of-class assignment we have set is tasking

students with choosing a certain number of

articles they find humorous and a selection of

articles they find confusing. Learners compare

the types of humor they find funny and

collaborate to decipher the difficult examples.

Responding to satirical news

Again, failure to recognize satirical news on

social media can be confusing or embarrassing

for English language learners. As with memes,

however, the language classroom provides a

safe environment where students can share and

respond to satirical news. A class-only online

page is easy to create, as we also suggested for

sharing and responding to memes. Considering

that this is a safe environment for learners to

examine and deepen their understanding of

English humor, class replies can include either

an appreciation of the satirical news examples

posted or questions to clarify the meaning

of the examples. While it is best to allow

learners to interact freely with their classmates,

the teacher can also supply explanations or

additional resources when necessary.

Suggestions for dierent prociency levels

As with verbal irony and memes, satirical

news is a form of humor used to mock

anything from daily trivial matters to serious

contemporary social issues. Teachers can focus

on the former when introducing satirical news

to lower-proficiency learners. Such satirical

items usually use relatively simple vocabulary,

and if not, the vocabulary can be simplified.

The teacher can also focus on helping lower-

level learners notice stylistic hints. For

example, satirical news sites are more likely

to use features such as all caps in headlines and

odd photos that are obviously edited in some

way. Meanwhile, teachers can give more-

proficient learners freedom in searching for

and discussing their own examples of satirical

news items. In addition, the teacher can

introduce satirical news to explore complex

topics, such as politics and media literacy.

CONCLUSION

Humor is a powerful tool that makes the

language-learning experience more interesting,

memorable, and engaging. In addition, humor

instruction about popular forms of humor in

English-speaking cultures can be integrated to

supplement any of the traditional four language

skills. Moreover, our research demonstrates

that training helps learners improve their

humor competency regarding satirical news

and sarcasm (Prichard and Rucynski 2019,

2020). However, the opening anecdote serves

as a warning that humor instruction is not

something to randomly tack on merely to

2021

ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM

13

americanenglish.state.gov/english-teaching-forum

Our aim in this article is to provide one practical framework

for how humor instruction about three common forms of

English-language humor can be carried out in the classroom.

make English classes more interesting. Proper

humor instruction involves careful scaffolding,

selection of materials and resources, and

design of activities.

While a growing number of researchers

advocate including a component of humor

instruction in the language-teaching

curriculum, our aim in this article is to provide

one practical framework for how humor

instruction about three common forms of

English-language humor can be carried out in

the classroom. Considering the multifaceted

and complex nature of humor, teachers still

need to take great care in implementing

humor instruction that is appropriate for the

proficiency level, curricular needs, cultural

background, and language-learning goals of

their students. A deeper understanding of

the humor of the target culture(s) empowers

English language learners as they acquire more

competence and confidence in communicating,

both face-to-face and digitally, in English.

REFERENCES

Bell, N. D., and A. Pomerantz. 2016. Humor in the

classroom: A guide for language teachers and educational

researchers. New York: Routledge.

Colston, H. L. 2017. Irony and sarcasm. In The

Routledge handbook of language and humor, ed. S.

Attardo, 234–249. New York: Routledge.

Henderson, S. 2017. Internet memes to learn and

practice English. In New ways in teaching with humor,

ed. J. Rucynski, Jr., 246–248. Alexandria, VA:

TESOL Press.

Kim, J., and J. P. Lantolf. 2018. Developing

conceptual understanding of sarcasm in L2 English

through explicit instruction. Language Teaching

Research 22 (2): 208–229.

Lems, K. 2013. Laughing all the way: Teaching English

using puns. English Teaching Forum 51 (1): 26–32.

Ohashi, L. 2017. Sharing laughs and increasing cross-

cultural understanding with memes. In New ways in

teaching with humor, ed. J. Rucynski, Jr., 274–276.

Alexandria, VA: TESOL Press.

Pimenova, N. 2020. Reading jokes in English:

How English language learners appreciate and

comprehend humor. In Bridging the humor barrier:

Humor competency training in English language teaching,

ed. J. Rucynski, Jr. and C. Prichard, 135–161.

Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Prichard, C., and J. Rucynski, Jr. 2019. Second

language learners’ ability to detect satirical news

and the effect of humor competency training. TESOL

Journal 10 (1): e00366.

———. 2020. Humor competency training for

sarcasm and jocularity. In Bridging the humor barrier:

Humor competency training in English language teaching,

ed. J. Rucynski, Jr. and C. Prichard, 165–192.

Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Rothermich, K., and M. D. Pell. 2015. Introducing

RISC: A new video inventory for testing social

perception. PloS ONE 10 (7): e0133902.

Rucynski, J., Jr. 2011. Using The Simpsons in EFL

classes. English Teaching Forum 49 (1): 8–17.

Rucynski, J., Jr., and C. Prichard, eds. 2020. Bridging

the humor barrier: Humor competency training in English

language teaching. Lanham, MD: Rowman and

Littlefield.

Shively, R. L. 2018. Learning and using conversational

humor in a second language during study abroad. Boston:

Walter de Gruyter.

Wulf, D. 2010. A humor competence curriculum.

TESOL Quarterly 44 (1): 155–169.

John Rucynski, Jr. is an associate professor in the

Center for Liberal Arts and Language Education at

Okayama University in Japan. He has edited two

volumes on humor in language education, New Ways in

Teaching with Humor and (with Caleb Prichard) Bridging

the Humor Barrier: Humor Competency Training in English

Language Teaching.

Caleb Prichard is an associate professor at Okayama

University in Japan. He has also taught in South Korea and

the United States. He co-edited Bridging the Humor Barrier:

Humor Competency Training in English Language Teaching with

John Rucynski, Jr. and has published several articles on

humor in second-language education. He has researched

reading strategy competency, among other areas.