Brigham Young University

BYU ScholarsArchive

**7$0$0 ,#(00$/1 1(-,0

Social Media Use and Its Impact on Relationships

and Emotions

Spencer Palmer Christensen

Brigham Young University

-**-41'(0 ,# ##(1(-, *4-/)0 1 '8.00"'-* /0 /"'(3$!52$#2$1#

/1-%1'$ -++2,(" 1(-,-++-,0

7(07$0(0(0!/-2&'11-5-2%-/%/$$ ,#-.$, ""$00!5"'-* /0/"'(3$1' 0!$$, ""$.1$#%-/(,"*20(-,(,**7$0$0 ,#(00$/1 1(-,0!5 ,

21'-/(6$# #+(,(01/ 1-/-%"'-* /0/"'(3$-/+-/$(,%-/+ 1(-,.*$ 0$"-,1 "1 0"'-* /0 /"'(3$!52$#2$**$, + 1 ,&$*-!52$#2

"'-* /0/"'(3$(1 1(-,

'/(01$,0$,.$,"$/ *+$/-"( *$#( 0$ ,#10+. "1-,$* 1(-,0'(.0 ,#+-1(-,0 All eses and Dissertations

'8.00"'-* /0 /"'(3$!52$#2$1#

Social Media Use and Its Impact on Relationships and Emotions

Spencer Palmer Christensen

A thesis submitted to the faculty of

Brigham Young University

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Arts

Kristoffer D. Boyle, Chair

Scott H. Church

Robert I. Wakefield

School of Communications

Brigham Young University

Copyright © 2018 Spencer Palmer Christensen

All Rights Reserved

ABSTRACT

Social Media Use and Its Impact on Relationships and Emotions

Spencer Palmer Christensen

School of Communications, BYU

Master of Arts

A large majority of the people throughout the world own a smartphone and access social media

on a daily basis. Because of this digital attachment, the author sought to understand to what

extent this use has impacted the users’ emotional well-being and offline interpersonal

relationships. A sample size of 627 participants completed a mixed-methods survey consisting of

Likert scale and short answer questions regarding social media use, emotional well-being and

interpersonal relationships. Results revealed that the more time an individual spent on social

media the more likely they were to experience a negative impact on their overall emotional well-

being and decreased quality in their relationships. Emotional well-being also mediated the

relationship between time spent using social media and the quality of that user’s relationships,

meaning that the more time a person spent on social media the more likely their emotional well-

being declined which then negatively impacted their relationships. The top three responses for

negative effects of social media use on emotions were frustration, depression, and social

comparison. The top three responses for negative effects of social media use on interpersonal

relationships were distraction, irritation, and decreased quality time with their significant other in

offline settings. An analysis of these, and other, results, along with relative implications, are

discussed.

Keywords: social media, emotional well-being, interpersonal relationships, uses and

gratifications

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I want to personally thank everyone who has contributed to helping me complete my

thesis, without whom I would not have met the requirements for graduation. My wife, Kaily, has

been my champion and supporter through all of graduate school and I thank her for her love and

companionship. My daughter, Evelyn, served as my motivation to push through the hard times so

that I could support her. To my committee: Kris Boyle, Scott Church, and Robert Wakefield, I

thank you for your advice, insights, and counsel that has shaped my thesis into what it has

become; I could not have made it this far without your help. Lastly, to Chris Wilson, Kevin John,

and Jared Hansen, I thank you for your help in organizing and analyzing my quantitative results

as my knowledge of SPSS was very limited.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE .............................................................................................................................. i

ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................... iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................... iv

Introduction ................................................................................................................................1

Literature Review ........................................................................................................................3

Uses and Gratifications Theory ...............................................................................................3

Benefits of Social Media .........................................................................................................4

Interpersonal Relationships in a Digital Age ............................................................................8

FOMO and Anxiety ............................................................................................................... 10

Depression and Loneliness .................................................................................................... 13

Research Questions/Hypotheses ............................................................................................ 15

Method ..................................................................................................................................... 16

Results ...................................................................................................................................... 23

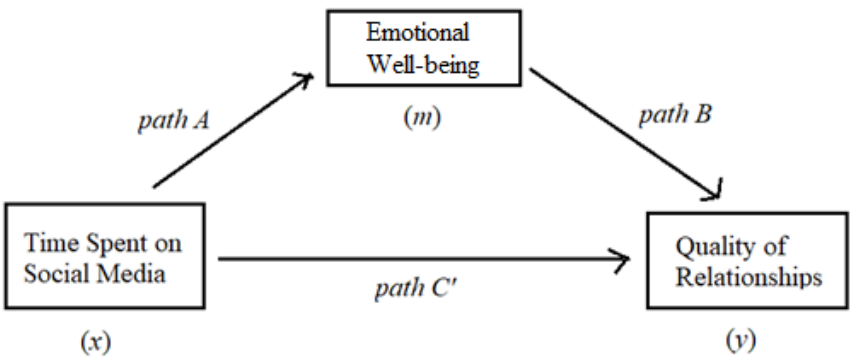

Figure 1 ................................................................................................................................. 26

Figure 2 ................................................................................................................................. 27

Discussion ................................................................................................................................. 32

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ 45

References ................................................................................................................................ 47

v

Appendix A—Social Media Survey .......................................................................................... 54

Appendix B—Tables ................................................................................................................. 58

Table 1 .................................................................................................................................. 58

Table 2 .................................................................................................................................. 58

Table 3 .................................................................................................................................. 58

Table 4 .................................................................................................................................. 60

Table 5 .................................................................................................................................. 60

Table 6 .................................................................................................................................. 60

Table 7 .................................................................................................................................. 61

Table 8 .................................................................................................................................. 62

Table 9 .................................................................................................................................. 62

Table 10 ................................................................................................................................ 63

Table 11 ................................................................................................................................ 63

Table 12 ................................................................................................................................ 64

Table 13 ................................................................................................................................ 65

Table 14 ................................................................................................................................ 66

Table 15 ................................................................................................................................ 67

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 1

Introduction

Social media use is a ubiquitous phenomenon (Elhai, Levine, Dvorak, & Hall, 2016;

Pittman, & Reich, 2016; Quinn, 2016). Research shows that 90% of adults own a smartphone

(Pew Research Center, 2014). Additional research indicates that 72% of Americans and an

average of 43% of the world own a smartphone (Elhai et al., 2016) while more than 71% of

American adolescents, ages 13-17, regularly use Facebook (Beyens, Frison, & Eggermont,

2016). Facebook is the most popular social networking site in the world containing 1.5 billion

active users with at least 900 million of these logging into the site daily (Ryan, Chester, Reece, &

Xenos, 2014). Pittman and Reich (2016) synthesized these findings to indicate that 91% of

smartphone owners used social networking sites on their phone at least once every day.

Due to the prevalence of social media in our lives, the people of the world are more

interconnected than at any other time in history. Because of this, there could be a perception that

people are happier because they are connected with more people. In fact, Nezlek, Richardson,

Green, and Schatten-Jones (2002) found that participants who were more socially active [offline]

reported greater life satisfaction and higher psychological well-being. However, social

interaction in the virtual world tells a different story, especially when those online connections

impact our offline interpersonal relationships.

Throughout the past decade, social media use has grown exponentially and has changed

the way we communicate with each other. Facebook is the most used online media platform in

the world (Beyens, Frison, & Eggermont, 2016; Steers, 2016) and has a high potential for

impacting the emotions and relationships of adolescents who use it (Kross et al., 2013). The

primary purpose of this paper is to determine if a relationship exists between excessive social

media use and the overall emotional well-being of that individual as well as the quality of the

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 2

individual’s interpersonal relationships. The secondary purpose is to determine if the relationship

between time spent on social media and the quality of the interpersonal relationships is mediated

by the emotional well-being of the user such as fear of missing out (FOMO), anxiety, depression,

and loneliness as seen through the lens of uses and gratifications theory.

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 3

Literature Review

Uses and Gratifications Theory

The most common theory used to understand why people engage with social media is

uses and gratifications theory (U&G). This theory was first proposed by Elihu Katz and his

partners Jay Blumler and Michael Gurevitch in 1973 and was used to study the motives people

have for engaging with the media that they do in order to gratify their needs (Katz, Blumler, &

Gurevitch, 1973). U&G is a psychological communication perspective and theorizes that

individuals are actively engaged in seeking out media that they believe will satisfy certain needs

(Katz et al., 1973; Rubin, 2009). U&G posits that media consumers make their own choices on

which media and what type of media they consume in order to receive maximum gratification for

their needs (Alajmi et al., 2016). To summarize, U&G focuses on consumers’ motives for using

specific types of media and the satisfaction they receive from their use.

People make their own decisions on which media to engage with in order to satisfy their

needs, however those needs are not always obtained. Often times, the gratifications sought are

not the same as the gratifications obtained and although strongly correlated, continued use of a

medium over time implies that the gratifications obtained strongly reinforce continued use of that

same medium in order to continue seeking the gratifications originally sought after (Levy &

Windahl, 1984; Palmgreen, Wenner, & Rayburn, 1980).

Blumler and Katz (1974) synthesized U&G by explaining that is was focused on social

and psychological needs that create certain expectations of mass media which lead to particular

patterns of media exposure and result in need gratification as well as other consequences,

although these other consequences are perhaps unintended. Blumler et al. (1974) further

explained that there were five main components to U&G:

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 4

1. The audience is believed to be active

2. The linking of gratification and media choice lies with the consumer

3. The media compete with other sources of gratification

4. The goals of mass media are derived from the content created by the consumers

5. Value judgments of mass media should be suspended while consumer orientations are

explored

While uses and gratifications theory was once used to explore the gratifications gained

from TV and radio use, it has since been adapted for the study of social media and its various

elements such as gratifications from Facebook use (Park, Kee, & Valenzuela, 2009; Quan-Haase

& Young, 2010), privacy regulations online (Quinn, 2016), Chinese social media apps (Gan,

2018), social capital (Petersen & Johnston, 2015), and motivations for social media use (Cheung,

Chiu, & Lee, 2011), among others which all contribute to the credibility of using this theory for

the purposes of the present study. Further evidence supporting the use of this theory to study

social media is that the five main components of U&G proposed by Katz et al. (1974) can be

applied to social media use. U&G is widely considered a pro-social theory that highlights the

benefits for using various types of media and some of those benefits are worth taking the time to

examine.

Benefits of Social Media

With a large portion of the world accessing social media on a daily basis, there is ever-

increasing evidence that social media offer a varied experience for each user and that some of

those experiences produce positive results. These benefits offer possible explanations as to why

social media usage is continuing to grow throughout the world. One of the most common reasons

that people use social media is to stay connected with their friends and family members

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 5

(Pempek, Yermolayeva, & Calvert, 2009; Subrahmanyam, Reich, Waechter, & Espinoza, 2008;

Wang, Tchernev, & Solloway, 2012). Social media offer an easy way of keeping in touch and

maintaining relationships with people who are often beyond the close proximity of frequent

communication. Subrahmanyam et al. (2008) added to this by suggesting that many social media

users use it to both connect and reconnect with others indicating that there was overlap between

participants' online and offline networks. However, the overlap was imperfect; the pattern

suggested that many online users engaged in different online contexts to manage various parts of

their offline connections.

Online profiles often reflect some version of the offline lives they represent. In these

online profiles, social media users express certain elements of themselves that they want others

to see. In other words, the user manipulates the preferences of their profile to build an online

identity (Pempek et al., 2009). In addition to helping establish an online identity, social media

use also offers gratification in certain emotional, cognitive, social, and habitual areas of the

users’ lives (Wang et al., 2012). Generally however, only some of these areas are fully gratified

leading to an accumulation of ungratified needs which drives subsequent social media use and

contributes to the user becoming addicted or, at the very least, using social media excessively

unless those needs are satisfied in offline situations.

Desired gratifications on social media often drive the behaviors that lead to those

gratifications. Hayes, Carr, and Wohn (2016) explored the meaning that “liking” a post on

Facebook (or a “favorite” on Twitter, etc…) had for both the original poster and the one who

“liked” the post. The results of the study indicated that people devalued Facebook “likes” owing

to the fact that they were more reactionary than conscious. Favorites on Twitter did not matter

because it was more about the content than the social capital. Liking on Instagram was more

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 6

selective. Receiving upvotes on Reddit contributed to the social currency of the post making it

more trustworthy and accepted by other redditors.

Additionally, findings from the study by Hayes et al. (2016) revealed four main

motivations for sending a paralinguistic digital affordance (PDA—aka “liking,” or “favoriting” a

post) and three main gratifications for receiving a PDA. The motivations for sending a PDA

included: literal interpretation—the PDA was an evaluation of the content; acknowledgement of

viewing—the PDA served as an acknowledgement to the poster that they had seen the post;

social support—the PDA served as a way of saying that you supported the person in their

endeavors; and lastly utilitarian purposes—the PDA served as a personal score card to make

themselves feel better about sending out so many PDA’s to so many people. On the flip side,

those who originally sent the post received three main gratifications from PDA’s: emotional

gratification—participants reported feeling happy when they received a PDA; status

gratification—the more PDA’s their post received the higher their social status; social

gratification—PDA’s served to create or enhance interpersonal relationships (Hayes et al., 2016).

The results from Hayes et al. (2016) explained that there were various gratifications

people received from using social media. However, additional research will help to further

illuminate this phenomenon. Oeldorf-Hirsch and Sundar (2016) explored motivations for why

people share photos online. The participants were asked questions regarding why they share

photos online and the results revealed four categories of gratifications: seeking and

showcasing—the need to keep up with the world and keep tabs on others; technological

affordances—the features of the platform make it easier to share; social connection—

maintaining close relationships and creating new relationships; and reaching out—wanting to

reach a wide audience and receive feedback on their photos. These findings indicate that photo

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 7

sharing is driven by social needs and that the platform offered special affordances that enabled

the behavior (Oeldorf-Hirsch & Sundar, 2016).

Interactions on social media have frequently been referred to as bridging and bonding

social capital (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007; Putnam, 2000). Bourdieu and Wacquant

(1992) define social capital as “the sum of the resources, actual or virtual, that accrue to an

individual or a group by virtue of possessing a durable network of more or less institutionalized

relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition” (p. 14). As it relates to social media, social

capital is the relationships established online that enrich virtual interactions. Bridging and

bonding are often placed as opposites to each other, but this would be an incorrect assumption of

these concepts. Rather, they are relatable dimensions along which different forms of social

capital can be compared. Bridging social capital is composed of several elements including:

connecting with people who think differently from ‘me;’ ties are generally weaker and more

fragile, but they allow for more open doors that bonding does not allow; more likely to foster

social inclusion; good for linking external assets and information diffusion; good for getting

ahead; and can generate a broader range of identities. Examples include: loose connections,

lesser-known classmates at school, LinkedIn connections, and your brother’s boss, among others.

Bonding social capital is comparable, but with key differences: connecting with like-minded

individuals; ties are stronger and are usually kept within a smaller circle of connections; fosters

social exclusion due to strong in-group loyalty; good for getting by; and can be referred to as an

echo chamber of individuals who think alike without opposing ideas. Examples include: families,

closed group forums, and fraternities (Putnam, 2000).

When a user engages with others on social media they incorporate both bridging and

bonding techniques in order to maximize the benefits of their social media usage in the form of

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 8

social capital. Essentially, the better well-established an individual’s social capital is the greater

their realm of influence online. However, users must also exercise caution when connecting with

others so that they do not become too vulnerable by over-exposing their personal information.

Quinn (2016) found that there were four valid concerns about sharing personal information

online: information control—controlling the amount of information you send out to other people;

power loss—when you share your personal information with others they gain some degree of

power over you; identity loss—perceived damage; future life of information—perceived

likelihood of harm. Considering these levels of privacy, it is interesting to see how these privacy

behaviors affect the way users engage with others on social media as well as how those online

behaviors impact the relationships that are formed both on social media and in the physical

world.

Interpersonal Relationships in a Digital Age

Interpersonal relationships are relationships that take place between two or more people

and can include both online (thanks to the Internet) and offline interactions. Although important

and worth the time to explore, the present study does not examine online relationships in depth.

Rather, this study is interested in understanding how individuals use the Internet, in particular

social media, and to what extent it affects their offline interpersonal relationships. Some research

suggests that social media are already changing the way that we interact with each other offline.

Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas (2016) coined a new term known as “phubbing” which

represents “the act of snubbing someone in a social setting by concentrating on one’s phone

instead of talking to the person directly” (p. 10). They found that this “phubbing” behavior was

growing increasingly more commonplace and acceptable and that people were beginning to see

this once-thought-of-as-rude behavior as normal. The extent to which people would phub others

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 9

was directly related to their level of smartphone addiction. As the proclivity of cell phone use

increases, the likelihood of phubbing occurring more frequently will also increase leading to a

more permanent change in the way we interact with each other.

Hertlein (2012) noted that the Internet provides increasingly blurred boundaries between

online and offline relationships. In a study seeking to understand the role of technology in

changing family relationships, Hertlein (2012) found that the rules of interaction with online

peers had several negative effects on daily life such as compromising the function of offline

relationships, detracting from job performance, and increasing the potential for Internet

addictions. Coinciding with these findings, Abbasi and Alghamdi (2017) found that misusing

Facebook can lead to negative societal consequences such as social isolation, distrust in

relationships, infidelity, lack of social cohesion, Facebook addiction, and divorce.

Our online and offline relationships have grown to become so interconnected that what

we do in either of those relationships impacts the other. Kerkhof, Finkenauer, and Muusses

(2011) called this phenomenon a “syntopia” explaining that the physical/social situations and

history of a person influenced what they did and learned online which spilled over into their

offline experiences. Under this lens, Kerkhof et al. (2011) found that those with high compulsive

Internet use experienced decreased quality in their offline relationships, reported decreased

commitment in their relationships, and had more frequent conflicts with their partners.

Conversely, Jenkins-Guarnieri, Wright, and Hudiburgh (2012) found that those with

lower levels of perceived competency at initiating offline relationships was related to increased

use of Facebook. Additionally, heavy social media users have decreased interpersonal

competency at initiating offline relationships meaning that the more a person uses social media

the harder it is for them to initiate new relationships offline. Supporting these findings, Seo,

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 10

Park, Kim, and Park, (2016) revealed that a person who had developed a dependency to their cell

phone experienced decreased attention and increased depression which led to a negative impact

on their social relationships with their friends. Even when people would hide their online

addictions or relationships from their partners they still reported that daily tasks were unfinished

and that levels of sexual intimacy with their primary partner had decreased (Underwood &

Findlay, 2004).

Social media do not only impact our relationships with others, they also impact our

relationship with ourselves and how we perceive the world around us. Kerkhof et al. (2011)

found that compulsive Internet users were lonelier, more depressed, and generally exhibited

poorer social skills than noncompulsive Internet users indicating that these negative

characteristics were brought about by their overuse of the Internet. Additional research revealed

that overuse of social networking sites significantly affects the lives of adolescents with negative

consequences on their personal, psycho-social well-being (Marino, Vieno, Pastore, Albery,

Frings, & Spada, 2016). Finally, Seo, Park, Kim, and Park, (2016) claimed that the more

problematic mobile phone addiction becomes, the more people will experience decreased self-

esteem and emotional well-being.

From the aforementioned research, it is clear that our use of social networking sites

influences our offline relationships and vice-versa. To further explore the depth to which social

networking sites affect our emotions, four psycho-sociological problems will be placed under

scrutiny.

FOMO and Anxiety

Fear of missing out (FOMO) is the psychological mentality that individuals might be

missing out on a social opportunity or situation. This mentality requires that they stay constantly

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 11

connected with others and updated about what their friends are doing (Beyens et al., 2016; Elhai

et al., 2016). The need for these individuals to stay constantly connected with their peers has led

to problematic smartphone use. A side effect to overusing a smartphone is decreased emotional

self-control which is defined by two processes: decreased cognitive reappraisal (inability to

assess your mental or emotional state in a different way) and increased emotional suppression

(suppressing one’s emotions often leads to a buildup of pressure and stress) both of which lead to

an inability to regulate emotions properly (Elhai et al., 2016). Elhai et. al (2016) argued:

Overusing one’s smartphone does not account fully for depression or anxiety; rather,

other intervening variables may play a role. Specifically, less behavioral activation and

(for depression only) more emotion suppression appear to account for this relationship.

Problematic smartphone use may interfere with other pleasurable activities and disrupt

social activities thereby reducing behavioral activation and subsequently increasing

depression. It is possible that emotional suppression, a correlate of problematic use,

disrupts adaptive processing of emotions, which in turn is associated with greater

depression (p. 514).

While depression will be discussed in greater detail later on, this comment suggests that it is not

social media itself that is causing these mental problems, but rather the misuse/overuse/abuse of

it by those who use it.

In a study conducted by Lai, Altavilla, Ronconi, and Aceto (2016), an EEG brain scanner

was used to detect the parts of the brain that were illuminated when the participant was exposed

to certain images. In this study they examined FOMO, social inclusive experiences, and social

exclusive experiences. Their findings showed that those with higher FOMO ratings were more

aware of the state of mind of others involved in positive social interactions and they showed a

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 12

higher need for self-approval which could be the reason why people keep returning to social

media (Lai et al., 2016).

Closely related to FOMO is anxiety which manifests itself frequently in the lives of those

who use social media and experience FOMO. Cheever, Rosen, Carrier, and Chavez (2014)

sought to explore when anxiety manifested itself in the lives of college students who were

separated from their cell phones. After collecting reasons each participant used their cell phone

and acquiring data for how long each participant uses their cell phone for the activities they

mentioned, the researchers found that the average amount of time each college student spent on

their phone each day was 13 hours and the top listed reasons for their use, in order from most

used to least used, were as follows: texting, listening to music, visiting websites, talking on the

phone, using email, watching TV/movies, playing games, and reading books. The amount of

time for each activity was averaged together and divided into three categories of low daily usage

(1-7 hours), moderate daily usage (7.5-16.5 hours), and high daily usage (17-64.5 hours).

The findings of the study revealed that those who were low daily users experienced little

to no anxiety while taking the surveys. Those who were moderate users initially experienced

high anxiety due to the increased length of time to complete the second survey compared to the

time spent to complete the first survey, but the anxiety plateaued during the third survey. For the

high daily usage group there was a significant increase in the length of time spent to complete

each of the three surveys indicating that anxiety increased over time and continued to rise

(Cheever et al., 2014). These findings had less to do with whether or not the person was

separated from their phone and more to do with how heavy of a user they were. This study

highlights that people who use their phones excessively will experience high anxiety when they

are separated from them. This could explain why those who have their cell phones with them and

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 13

use them regularly will experience high rates of anxiety when they are separated from being

active on social media.

Depression and Loneliness

Along with FOMO and anxiety, depression and loneliness contribute to the mental health

problems caused by social media use. One study found that many high school and college

students are dealing with anxiety and depression rates that are five times higher than youth who

were studied during the Great Depression era (AP, 2010). There have been many theories as to

why this might be the case, but several scholars believe that heavy social media use, such as

Facebook and Instagram, may contribute to this growing problem (Tandoc, Ferrucci, & Duffy,

2015). In countries where social media use is high, reports show that loneliness and depression

have increased dramatically within the past decade (Pittman & Reich, 2016). There is no doubt

that increased social media use and higher rates of depression and loneliness are linked.

Tandoc et al. (2015) conducted a study where they found that heavy users of Facebook

experienced higher levels of Facebook envy than light viewers and that they reported feeling

more symptoms of depression. The study also found that heavy Facebook users engaged in

Facebook surveillance, which was akin to lurking, and that this behavior was mediated by envy

(Tandoc et al., 2015). In other words, those who were heavy Facebook users experienced higher

levels of envy and depression which caused them to engage in Facebook surveillance because the

more they saw on Facebook the more they wanted and the worse they felt.

Depression and loneliness go hand in hand with each other, but they are not the same

thing. Pittman and Reich (2016) expounded on the relationship between depression and

loneliness by surveying 253 students asking them about their experiences with image-based

social media platforms (Instagram and Snapchat) vs. text-based social media platforms (Twitter

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 14

and SMS texting). Their findings indicated that solely image-based platforms led to a happier,

more satisfied, less lonely life because images offered the intimacy that a face-to-face

conversation contains allowing the viewer to feel a stronger connection with the situation being

presented in the image. Text-based platforms showed no relationship to increased or decreased

psychological well-being (Pittman et al., 2016). These results might possibly explain one way to

overcome loneliness, however, one can still feel depressed without feeling lonely and vice-versa.

Loneliness is the lack of shared companionship with someone else. Depression is an internal

emotion experienced by oneself. When these two feelings are combined with social media use it

can cause a person to feel socially isolated and paralyzed to the point where they don’t think they

can do anything to get out of their situation.

Rosenthal, Buka, Marshall, Carey, and Clark (2016) conducted a longitudinal study that

examined families and their negative experiences on Facebook. Results indicated that all of the

negative Facebook experiences that were measured were significantly associated with depressive

symptoms (Rosenthal et al., 2016). This study is different from the others previously cited in the

present study because it deals with actual negative experiences causing depressive symptoms as

opposed to users comparing their lives with the good and happy lives they see on social media

and then choosing to feel depressed from it. Either way, the use of Facebook can cause an

increase in feelings of depression and isolation leading to loneliness.

There is a lot of research that has been conducted on how social media use affects the

individual who is using it for good or bad. A lot of research has also been conducted on why

people choose to engage with the types of media that they do. However, there is very little

research on how an individual’s choice to engage with certain types of media influences their

emotions and how those emotions then impact their offline interpersonal relationships. Based on

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 15

this analysis the author posits three research questions and several hypotheses in order to better

understand these phenomena:

Research Questions/Hypotheses

RQ1: How does the use of social media influence the quality of the user’s interpersonal

relationships?

RQ2: How does the use of social media influence the user’s overall emotional well-

being?

RQ3: Why do people use social media?

H1a: Increased time spent on social media will lead to decreased overall quality of the

users’ interpersonal relationships.

H1b: High frequency of accessing social media will lead to decreased overall quality of

the users’ interpersonal relationships.

H2a: Increased time spent on social media will lead to the user’s decreased overall

emotional well-being.

H2b: High frequency of accessing social media will lead to the user’s decreased overall

emotional well-being.

H3a: Emotional well-being mediates the relationship between time spent on social media

and the overall quality of the users’ interpersonal relationships.

H3b: Emotional well-being mediates the relationship between frequency of accessing

social media and the overall quality of the users’ interpersonal relationships.

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 16

Method

This study incorporates a mixed-method approach which includes a survey of

quantitative Likert-like questions and several qualitative short answer questions. The sample for

this study included social media users between 18-62 years of age. A survey was built in

Qualtrics and distributed on Facebook pages, sub-Reddit accounts, and Twitter from 9

February—9 March 2018. The sub-Reddit accounts where the survey was posted included:

“SampleSize,” “SaltLakeCity,” “Australia,” “AnythingGoesNews,” and “GradSchool.” All who

desired to participate were invited to do so. The sample size for this study was 750 participants

of whom 627 completed the survey.

The survey is made up of several scales. The first scale was adapted from Olufadi’s

(2016) ‘SONTUS’ which measures time spent on social media and has a Cronbach’s alpha of

.92. The participants answered two questions regarding their social media use: “I use social

media ___ each week (never, once, 2-3 times, 3+ times)” and “Each time I use social media I

typically use it for 0-10 min. 11-30 min. 30+ min. These questions were used in order to

determine if the participant was a high or low social media user as well as how frequently they

accessed social media each day.

The second scale was adapted from Rosenberg (1989) which includes 10 items and is

used to measure the emotional well-being of an individual. This scale was selected because it has

been tested to provide a high reliability and generalizability due to its sample size of over 5,000

participants. This scale is measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly

disagree) and all 10 of the following questions were used with no alterations:

1. I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others

2. I feel that I have a number of good qualities

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 17

3. All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure

4. I am able to do things as well as most other people

5. I feel I do not have much to be proud of

6. I take a positive attitude toward myself

7. On the whole, I am satisfied with myself

8. I wish I could have more respect for myself

9. I certainly feel useless at times

10. At times I think I am no good at all

The final portion of the survey is built from two separate scales which were combined to

study the quality of the participants’ interpersonal relationships. The first portion comes from

Hendrick’s (1988) 7-item Interpersonal Relations Scale which was adapted to match the format

of Garthoeffner, Henry, & Robinson’s (1993) 49-item Modified Interpersonal Relationship

Scale. Both scales are measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly

disagree) and includes the following questions that were originally separated into multiple

categories and have been adapted for the purposes of this study:

Interpersonal Relations Scale (Hendrick, 1988)

1. How well does your partner meet your needs?

2. In general, how satisfied are you with your relationship?

3. How good is your relationship compared to most?

4. How often do you wish you hadn’t gotten into this relationship?

5. To what extent has your relationship met your original expectations?

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 18

6. How much do you love your partner?

7. How many problems are there in your relationship?

Modified Interpersonal Relationship scale (Garthoeffner, Henry, & Robinson, 1993).

Trust

1. There are times when my partner cannot be trusted

2. My partner would tell a lie if he/she could gain by it

3. In our relationship, I have to be alert or my partner is likely to take advantage of me

4. My partner is honest mainly because of a fear of being caught

5. I’m better off if I don’t trust my partner too much

6. Even though my partner provides me with many reports and stories, it is hard to get an

objective account of things

7. There is no simple way to decide if my partner is telling the truth

8. In our relationship, I am occasionally distrustful and expect to be exploited

9. My partner can be counted on to do what he/she says they will do

10. I do not believe my partner would cheat on me even if he/she could get away with it

11. My partner can be relied on to keep his/her promises

12. My partner treats me fairly and justly

13. The advice my partner gives cannot be regarded as being trustworthy

14. I am afraid my partner will hurt my feelings

15. My partner pretends to care about me than he/she really does

16. My partner is likely to say what he/she really believes rather than what he/she thinks I want

to hear

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 19

17. I wonder how much my partner really cares about me

18. I believe most things my partner says

Self-disclosure

1. I can express deep, strong feelings to my partner

2. I feel comfortable expressing almost anything to my partner

3. In our relationship, I feel I am able to expose my weaknesses

4. I do not show deep emotions to my partner

5. I share and discuss my problems with my partner

6. I tell my partner some things of which I am very ashamed

7. It is hard for me to tell my partner about myself

8. I talk with my partner about why certain people dislike me

9. We are very close to each other

10. In our relationship, I’m cautious and play it safe

11. I discuss with my partner the things I worry about when I’m with a person of the opposite sex

12. I’m afraid of making mistakes with my partner

13. I touch my partner when I feel warmly toward him/her

14. It’s hard for me to act natural when I’m with my partner

Genuineness

1. My partner really cares about what happens to me

2. It is safe to believe that my partner is interested in my welfare

3. My partner is truly sincere in his/her promises

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 20

4. My partner is sincere and practices what he/she preaches

Empathy

1. My way of doing things is apt to be misunderstood by my partner

2. I feel my partner misinterprets what I say

3. I sometimes stay away from my partner because I fear doing or saying something I might

regret afterwards

4. My partner doesn’t really understand me

5. I sometimes wonder what hidden reason my partner has for doing nice things for me

Comfort

1. I seek my partner’s attention when I’m facing troubles

2. I would like my partner to be with me when I’m lonely

3. I feel comfortable when I’m alone with my partner

4. I would like my partner to be with me when I receive bad news

5. I feel relaxed when we are together

6. I face life with my partner with confidence

Communication

1. I listen carefully to my partner and help him/her solve problems

2. I understand my partner and sympathize with his/her feelings

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 21

Several of the questions are asked negatively and were reverse-coded during final

analysis of the data. In the survey provided in Appendix A the reverse-coded items are all in

italics.

Also included in this survey are several short answer questions offering additional

insights into why people use social media and what their perceptions are of how social media is

affecting their emotions and their relationships. These short answer questions were developed by

the author and they bring a qualitative element into this study thus forming it into a mixed-

methods study which helps to strengthen it by combining it with quantitative data because a

combination of these two methods is stronger than each one separately (Wisdom & Creswell,

2013). The four short answer questions include:

1. Why do you use social media?

2. Does your use of social media influence your emotions? If so, how?

3. Does your use of social media influence your relationships? If so, how?

4. Explain what you think it would be like to go one week without using your cell phone

or accessing any social networking sites.

The quantitative data were analyzed using the statistical software known as SPSS. The

independent variables are the amount of time spent on social media and the frequency with

which the individual accessed the social networking sites. The dependent variables are the

quality of the interpersonal relationships and the emotional well-being of the individual.

Emotional well-being also served as the meditating variable between the amount of time spent on

social media and the quality of the user’s interpersonal relationships. The qualitative questions

were coded by creating categories based on the answers of the participants and were grouped

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 22

together in a table. To test for reliability, the survey was examined by and distributed to

professors to make sure that the items on the survey worked for the purposes of this study.

Altogether, the survey consists of 73 questions including 4 qualitative short-answer

questions, 64 quantitative Likert scale questions, and 5 demographic questions. The demographic

questions asked about age, gender, ethnicity, romantic relationship status, and romantic

relationship length. The fourth qualitative question “Explain what you think it would be like to

go one week without using your cell phone or accessing any social networking sites” was

omitted during data analysis because it was found to be irrelevant to the direction of the study.

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 23

Results

The sample size for this study was 627. The average age for the participants was 28.36

with 510 participants being between the ages of 18-34 and 117 of the participants being between

the ages of 35-62. There were 373 (59.5%) female participants with 246 (39.2%) male

participants and 8 (1.3%) who preferred not to identify with a gender. The ethnicity of the

participants was as follows: White/Caucasian = 543 (86.6%), Hispanic = 14 (2.2%), Latino = 4

(.6%), African = 7 (1.1%), African American = 7 (1.1%), Asian = 14 (2.2%), Native American =

2 (.3%), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander = 4 (.6%), European = 15 (2.4%), Other = 17

(2.7%). The status of the participants’ relationships were as follows: single, never married = 198

(31.6%), currently in a relationship = 153 (24.4%), married = 259 (41.3%), divorced = 13

(2.1%), separated = 4 (.6%). Finally, the length of time that participants were in the relationship

they said they were in is as follows: not currently in a relationship = 145 (23.1%), less than one

year = 72 (11.5%), between 1 and 3 years = 117 (18.7%), between 3 and 7 years = 119 (19.0%),

between 7 and 10 years = 52 (8.3%), and more than 10 years = 122 (19.5%). Of this sample, 278

(44.3%) participants indicated that they spend 0-10 min. on social media each time they access it,

with 255 (40.7%) spending 11-30 min. and 94 (15%) spending 30+ min. Lastly, 55 (8.8%)

participants said that they access social media at least one time daily, 131 (20.9%) accessed

social media 2-3 times daily, and 441 (70.3%) access social media 3+ times every day. Those

who said that they never use social media were removed from the study as the author was not

interested in studying those who did not spend time on social media (see Tables 1-7).

Hypothesis 1a stated that increased time spent on social media would lead to decreased

overall quality of the users’ interpersonal relationships. A Spearman’s rho correlational analysis

was conducted to examine the relationship between the amount of time spent on social media

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 24

and the quality of the user’s interpersonal relationships. The analysis was significant, r(627) = -

.09, p < .05 (see Table 8). Chronbach’s alpha was reported as α = .95. These tests verified that

for participants who spent more time on social media the quality of their interpersonal

relationships decreased, thus H1a was fully supported.

Hypothesis 1b stated that increased frequency of accessing social media would lead to

decreased overall quality of the users’ interpersonal relationships. A Spearman’s rho

correlational analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between how frequently an

individual accessed social media and the quality of their interpersonal relationships. The analysis

was not significant, r(627) = -.04, p > .05 (see Table 8), indicating that how frequently an

individual accessed social media did not impact the quality of their relationships. Thus, H1b was

not supported.

Hypothesis 2a stated that increased time spent on social media would lead to the user’s

decreased overall emotional well-being. A Spearman’s rho correlational analysis was conducted

to examine the relationship between the amount of time spent on social media and the user’s

overall emotional well-being. The analysis was significant, r(627) = -.115, p < .001 (see Table

8), indicating that for those who spent more time on social media their emotional well-being

decreased. In other words, social media contributed to the user experiencing negative emotions

and moods. Thus H2a was fully supported. To further support H2a, a one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) was calculated on how much time a user spent on social media and their

emotional well-being. The analysis was significant, F(2, 624) = 6.39, p = .002 (see Table 10).

Participants who spent 30+ min. on social media per session experienced the greatest decrease in

their emotional well-being (M = 3.57, SD = .92) compared to those who spent 11-30 min. (M =

3.77, SD = .84) or those who only spent 0-10 min. (M = 3.91, SD = .73; see Table 9). To verify

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 25

these results, a Bonferroni Post Hoc test was conducted to find the mean difference between

those who spent 0-10 min. on social media and those who spent 30+ min. (M D = .333*, SE =

.096, p = .002; see Table 11). Once again, H2a was fully supported.

Hypothesis 2b stated that high frequency of use on social media would lead to the user’s

decreased overall emotional well-being. A Spearman’s rho correlational analysis was conducted

to examine the relationship between how frequently an individual accessed social media and

their overall emotional well-being. The analysis was not significant, r(627) = -.01, p > .05 (see

Table 8), indicating that how frequently an individual accessed social media did not impact their

emotional well-being. Thus H2b was not supported.

The author also proposed that emotional well-being could serve as a mediator to the

relationship between time spent on social media and relationship quality, as well as mediate the

relationship between the frequency of using social media and relationship quality. Using a

conditional process modeling program called PROCESS (Hayes, 2008, 2013), the author ran a

hierarchical regression analysis to test H3a and H3b, which posited that emotional well-being

could serve as a mediator for the relationship between social media use and relationship quality.

In H3a, the PROCESS tool revealed that the predictor—time spent on social media—and the

outcome—relationship quality—were mediated by emotional well-being, F(1,625) = 11.80, p =

.0006. Time spent predicted the mediator (emotional well-being) along path A at a significant

value, r = .14, p < .001; b = -.1601, t(625) = -3.44, p = .0006. The mediator then affected the

quality of relationships along path B at a significant value, r = .37, p < .001; b = 2.73, t(624) =

8.52, p < .000. This significance is greater than the original relationship between the time spent

and the quality of the relationships (path C’), r = .08, p < .05; b = -.03, t(624) = -.82, p > .05.

Thus, H3a was fully supported (see Table 12).

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 26

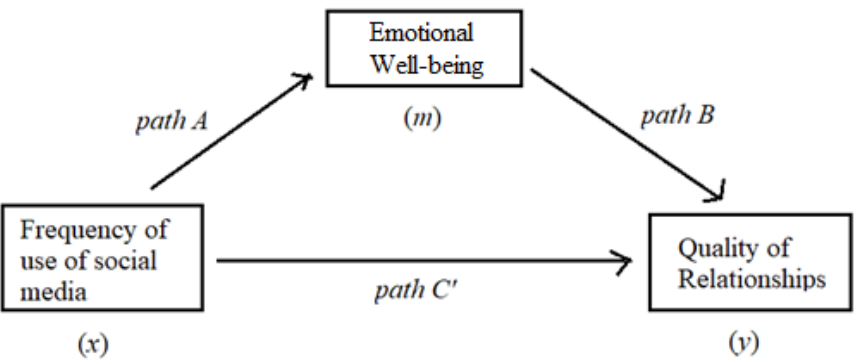

“In H3b, the PROCESS tool revealed that the predictor—frequency of social media

use—and the outcome—relationship quality—was not mediated by emotional well-being, since

path A was not significant, b = -.04, t(625) = -.82, p > .05. Thus, H3b was not supported (see

Table 12).

Based on these results, the author was able to create models to map the regression

between the mediator (emotional well-being) and the independent and dependent variables which

are included below:

Figure 1

Emotional well-being mediates the relationship between time spent on social media and the

overall quality of the users’ interpersonal relationships (supported).

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 27

Figure 2

Emotional well-being mediates the relationship between frequency of accessing social media and

the overall quality of the users’ interpersonal relationships (not supported).

The three research questions provide the qualitative part of this study and will now be

analyzed. Each of the short answer questions from the survey were coded and categorized based

on a reading of the participant’s responses to each question. Upon completion of the coding,

some categories were grouped together to form a more cohesive understanding of the topic being

discussed.

RQ1 explored the role that social media played in influencing interpersonal relationships.

In the survey, the question was phrased “Does your use of social media influence your

relationships? If so, how?” Of the 750 partially complete surveys, 643 participants answered this

question (see Table 13).

Of the 643 participants who answered this question, 929 responses were recorded due to

the participants’ responses being placed into multiple categories. The most common response

was that social media use did not influence their relationships. There could be several reasons for

this. One possible explanation is that the question was too vague for an adequate response to be

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 28

warranted leading to the response of “no, it does not influence my relationships.” A second

possibility is that those who responded this way were telling the truth and social media does not

influence their relationships. Previous research, and data found in this study indicate that this is

likely not the case, but without the ability to contact the participants and ask them, these results

are inconclusive. Finally, a third possible explanation is simply survey fatigue as this question

was presented at the end of the survey and the participants were likely tired of answering

questions.

The remaining data are more concrete. For the negative results, 380 participants

responded that social media negatively impacted their relationships by affecting various elements

of their lives (see Table 13). The most common response for the negative effects of social media

on relationships is that it distracts the user from engaging in face-to-face interactions with other

people or activities, thus making the user less social offline. The second most popular response

to this research question included that social media use made the user more edgy, irritated,

impatient, jealous, judged, ignored, or wanting to escape in their relationships. The last notable

responses for the impact social media use has on the user’s relationships included that they spent

less quality time with their significant other offline and that they spent more time comparing

their relationship to those they saw online thus resulting in a decreased overall satisfaction in

their own relationship.

The positive results were similar, in that 331 participants responded that social media

played a positive role in their relationships, with the exception of the category “Happier in my

relationships with less time on social media” due to the fact that the relationship was benefitted

by reducing the amount of time spent on social media so as to spend more quality time offline

with their significant others. The top response for this section was that social media allows for

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 29

people to “keep in touch” with their relationships, especially with close friends and family

members. Other top answers for this section include that social media use strengthened their

relationship in some way and they used it to share images, gifs, memes, or videos that they

thought their significant other would appreciate.

RQ2 examined the role that social media played in influencing the emotional well-being

of the user. In the survey, the question was phrased “Does your use of social media influence

your emotions? If so, how?” Of the 750 partially complete surveys, 668 participants answered

this question (see Table 14).

Of the 668 participants who answered this question, 1,294 responses were recorded due

to the participants’ responses being placed into multiple categories. The categories of “FOMO,”

“Anxiety,” “Depressed,” and “Lonely” were used because they had been shown to be influenced

by the use of social media in the past (Elhai et al., 2016; Cheever et al., 2014; Tandoc, Ferrucci,

& Duffy, 2015; Pittman & Reich, 2016, respectively). “Depressed/sad” was the category with the

most responses of these four (115). 127 participants responded that social media did not

influence their emotions. The majority of the participants experienced negative emotions from

their use of social media with the largest negative category (153) being that social media

influenced them to feel frustrated, annoyed, irritated, distracted, or stressed with 115 of the

participants responding that they felt depressed or sad from their use. Social comparison (107)

was the third most popular response followed by life dissatisfaction (84) and anger (57) or

wasted time (57). In addition to the remaining categories found in Table 14, other emotions were

mentioned throughout the responses that are worth mentioning, however, they were not abundant

enough to merit their own category. These additional negative emotions include: doubt, worry,

and being frightened or scared.

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 30

The happy/positive category holds the highest number (152) of responses for users who

reported receiving benefits from using social media indicating that their use of social media

influenced them to feel happy or positive from their interaction online. Several participants

responded that humor (43) was an affected emotion indicating that their use of social media

caused them to laugh or that the content they viewed was funny to them. Similar to RQ1, a small

number (31) of responses indicated that people were happier when they spent less time on social

media. This study includes a lesser-known term called “Mudita (23),” or sympathetic joy, which

is a Buddhist term for finding joy in the happiness and success of others (Salzberg, 1995). This

concept is the opposite of schadenfreude which is the pleasure we feel due to another’s

misfortune. Mudita was selected because there is no word in the English language that

encapsulates the idea of sympathetic joy, and it became a category because several participants

responded that they were happy for their friends or family members when they saw good things

happen to them such as getting married, graduating from school, or starting a new job. For

Mudita to be real, the observer cannot receive any direct benefit from the other person’s success;

the observer is simply happy for the other because of their success with no reward on behalf of

the observer. The common scenario used to describe this idea is the happiness a parent feels for

the success of their child (U Pandita, 2006).

RQ3 was simpler than RQ1 and RQ2 as it merely dealt with reasons why people use

social media. RQ3 was phrased “Why do you use social media?” Of the 750 partially complete

surveys, 680 participants answered this question (see Table 15).

Supporting what has been established in previous research, the top reason as to why

people use social media is to connect with friends and family on a regular basis (461). According

to this data set, the second most common response was to read/watch the news (188), but seeing

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 31

as a large portion of this sample came from Reddit, this is not surprising because Reddit is a

large news aggregate. Other reasons that people use social media are to find fun/entertaining

content (176), learn something new (91), because they are bored (77), to waste time (59), to

create or share content (55), for work/business (48), to escape their offline life or emotions (43),

and to learn about and participate in local events (25).

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 32

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to determine if a relationship existed between

excessive social media use and the overall emotional well-being of that individual as well as the

quality of the individual’s interpersonal relationships. A mixed-methods survey was distributed

on Facebook and Reddit and a sample size of 627 participants completed the survey. The

quantitative results were analyzed using SPSS and the qualitative responses were coded into

categories.

The results from H1a revealed that the more time an individual spent on social media the

more the quality of their relationships decreased. This supports findings by Kerkhof et al. (2011)

who also found that those with high compulsive Internet use experienced decreased offline

relationship quality. Results from H1b revealed that the number of times a user accessed social

media, or the frequency, did not play a significant role in altering their relationships. This is

somewhat surprising considering that the majority of the participants (70.3%) responded that

they accessed social media more than three times each day (see Table 2). However, upon further

consideration, these results are akin to picking up the TV remote and idly flipping through the

channels. By spending only a few seconds on each channel the viewer is not affected very

greatly, but if the viewer were to stop and watch one of the shows on TV, the content of that

show would be more influential on the viewer. These findings also support Hertlein (2012) who

found that interaction with online peers contributed to compromising the function of offline

relationships and increased the potential for Internet addictions. To summarize, a person may

access social media several times each day to respond to messages, check notifications, or even

lightly browse their feed, but their frequency of use is not as important as how long they spend

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 33

using social media which serves as a much more influential factor in altering their thoughts that

eventually lead to a change in the way they interact with others.

The results for H2a found that excessive use of social media was correlated with

decreased overall emotional well-being of the user. This supports Seo et al. (2016) who found

that cell phone dependency, and by extension social media usage, led to decreased attention and

increased depression which negatively impacted their social relationships. Cell phone addiction

also contributed to declining self-esteem and emotional well-being. Although counterintuitive,

staying connected to the world through the use of cell phones actually makes us more isolated in

the more important areas of our lives such as spending time face-to-face with those in our close

proximity.

The results found in H2a also support several other studies that have examined various

effects of social media use on emotions. Seo, Park, Kim, and Park, (2016) found that a person

who had developed a dependency to their cell phone experienced decreased attention and

increased depression which led to a negative impact on their social relationships with their

friends. They also claimed that the more problematic smartphone addiction becomes the more

people will experience decreased emotional well-being and increased anxiety (Seo et al., 2016;

Cheever et al., 2014). Kerkhof et al. (2011) found that compulsive Internet users were lonelier,

more depressed, and generally exhibited poorer social skills. Lastly, Tandoc et al. (2015) found

that heavy Facebook users experienced higher levels of envy and depression causing them to

engage in Facebook surveillance because the more they saw on Facebook the more they wanted

and the worse they felt.

The results for H2b revealed that frequency of social media use had the same impact on

emotional well-being as it did on relationships from H1b: none. The frequency of accessing

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 34

social media has little to do with relationships or emotions, but the amount of time spent on

social media serves as the more important variable that has a more direct impact on the quality of

the relationships of the user and their overall emotional well-being. In spite of this, it is possible

that frequently accessing social media, even for short periods of time, disrupt the free flow of

thought that leads to deeper thoughts and personal awareness. One participant remarked on this

thought by saying, “social media takes away from critical time to be alone with oneself and not

being distracted by something. I think social media usage results in a mental health decline not

because it results in a feeling of being left out from seeing what everyone else is up to, but

because people feel the need to be entertained constantly and don't know how to be by

themselves anymore.”

The secondary purpose to this study was to determine if the relationship between time

spent on social media and the quality of the interpersonal relationships could be mediated by the

emotional well-being of the individual using social media. Conclusive results from H3a revealed

that emotional well-being did indeed serve as a mediator for time spent on social media and the

quality of that user’s interpersonal relationships. To summarize, there is a direct inverse link

between time spent on social media and emotional well-being as well as relationship quality

separately. Also, when emotional well-being is introduced as the mediator, the direct relationship

between time and relationship quality disappears and a new link forms between time on social

media and relationship quality through emotional well-being and it turns into an indirect inverse

relationship.

Expressed in simple terms, when a person spends excessive amounts of time on social

media they likely experience decreased emotional well-being, which contributes to them

experiencing decreased quality in their relationships. The results from H3a mean that when a

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 35

person uses social media for long periods of time their emotions are negatively impacted. After

the person is done using social media they carry their negative emotions with them and they play

a role in how the user interacts with others offline. This interaction is not always negative, but

the quality of that interaction is less than it could have been because the negative emotions the

user brought with them from their social media use impacted that interaction. Seo et al. (2016)

found similar results in their study revealing that a person who had developed an addiction to

their cell phone experienced increased depression which led to a negative impact on their social

relationships with friends.

Moving on to the qualitative portion of this study, the three research questions offered an

in-depth look at what takes place within the minds of those who use social media. For RQ1, the

top response for negative results is that social media distracts the users from engaging in

wholesome activities and with people who are offline. This happens frequently when groups of

friends visit a restaurant together and one or all of them spend the majority of their time on their

cell phones without speaking to each other during the course of their visit. Chotpitayasunondh

and Douglas (2016) referred to this phenomenon as phubbing which is where people snub, or

ignore, others by using their phones. The results from RQ1 (see Table 13) support Abbasi and

Alghamdi (2017) who found that misusing Facebook can lead to negative societal consequences

such as social isolation, distrust in relationships, lack of social cohesion, and Facebook addiction.

Further supporting this claim, one of the participants in the present study responded: “I notice a

difference in me and my partner’s behavior when we are on social media for long periods of time

during any given day. We are less patient and a lot more anxious or on edge. We are more likely

to misunderstand each other or start an argument. We tend to be a lot more lazy.”

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 36

The third most popular response for RQ1 was that the quality time spent with people

offline was diminished because of their social media usage. This response directly supports H1a

because it shows that people are aware that their social media use plays a role in harming the

quality of their relationships. One participant summarized the entire purpose of this study

perfectly,

When I use it too much I am inclined to think badly of myself and of the world. I am also

more irritable with my children when I am currently using social media and they need

me.

Other notable responses further support these results. 42 participants stated that they

compare their relationship with relationships they see online leading to them feeling more

dissatisfied in their current relationship. This response was also found to be in the top three for

RQ2. One participant hit the nail on the head when they said, “my monster of comparison, when

it was raging, my marriage would really suffer because I would get angry at what we didn’t have

and not be grateful for what we do have. This would make [my husband] feel like a failure and

bad because he couldn’t provide any of it at the time.” This participant felt that her social media

use put a strain on her relationship with her husband, even when he was not using social media,

because she was comparing her life to those she saw online. This is one of the many examples

found in this study that demonstrate this effect.

Other negative effects that participants said resulted from their social media use included

increased distrust towards others, increased isolation, increased emotional detachment, and

increased unrealistic expectations (see Table 13 for full list).

Although the data from RQ1 strongly indicate that social media are a terrible influence in

the lives of users, they are not completely negative. In fact, the most popular reason people use

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 37

social media is to keep in touch with close friends and family members (Pempek, Yermolayeva,

& Calvert, 2009; Subrahmanyam, Reich, Waechter, & Espinoza, 2008; Wang, Tchernev, &

Solloway, 2012) and the responses in the present study support this claim. Participants also

indicated that social media were used to strengthen their relationships with people they were

close to through connecting and chatting with them, sharing memes and gifs, and receiving

updates on their lives that allow for opportunities to bond. Several participants even said that

social media help them to form new relationships that they never would have otherwise.

This balance between the positive and negative results from social media use is hard to

maintain and the data from RQ1 and H1a seem to push toward the negative. In fact, 20

participants who responded to RQ1 and 31 participants who responded to RQ2 said that they

believed they were happier in their relationships and emotions when they decreased their social

media use indicating that it was their social media use that was causing some degree of strain on

their relationships. One participant stated,

I used to spend a lot more time on social media, but I found that it made me unhappy. I

became jealous of others and their success. I began to compare myself to them, and

thought less of myself. One day a few months ago, I got sick of it, and I deleted

everything besides Facebook…. Since then, I have been way happier, and I have grown

to see myself in a much better way. I am also happier for those around me.

The data from RQ2 indicate that social media has a widely negative impact on the

emotions of those who use it with a small positive influence. The four original emotions

discussed earlier (FOMO, depression, loneliness, anxiety) will be examined first. Of these four,

depression scored the highest with 115 respondents saying that their social media influenced

them to feel depressed/sad for a variety of reasons. Combining this finding with the 43

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 38

participants who mentioned envy/jealousy was a common emotion for them offers support to

Tandoc et al. (2015) who said that heavy social media users experienced higher levels of envy

and reported feeling more symptoms of depression.

FOMO placed second among these original four, however it placed 9

th

overall among the

categories of negative emotions. One of the main drawbacks to FOMO is that it motivates the

individual to engage in social surveillance where they are constantly worrying about what

everyone else is doing and whether or not they are being included. This behavior encourages the

individual to stay on social media for longer periods of time so that they don’t miss out on any

opportunities and they return to social media more frequently in order to satisfy their higher need

for self-approval (Lai et al., 2016). One participant supported this finding by saying, “I have

found that using social media makes me hyper-aware of others, and more easily able to fall into

tribalistic thinking. It becomes a lot easier to get fired up about something and say ‘oh that

person is such an idiot,’ compared to if I was talking to someone in person.”

Loneliness came third with people saying their social media use made them feel

disconnected from their peers even though they were connected online. One participant stated,

“Often times, social media can make me feel more isolated from the people I follow, and the

people around me. I can also leave social media sites feeling more self-conscious and

depressed.” There is so much depression, anxiety, and loneliness that seem to be growing, but

these are often related to trivial things such as having a Netflix series end. There is little doubt

that these emotions are becoming more frequent, but are they perhaps related to more shallow

problems instead of real issues?

Anxiety came last out of the four original emotions. Several people responded that they

felt anxiety in connection with other emotions and that they felt it most strongly when they were

SOCIAL MEDIA USE 39

separated from either their cell phones or social media (Cheever et al., 2014). One participant

said, “sometimes, I'll see a cute couple or something and I'll get anxious because I'm so lonely.”

Another participant stated, “it makes me anxious when there’s a lot of bad news.” A third

participant remarked, “sometimes I feel anxious because I wonder why I haven’t been able to

secure a marriage relationship at this point in my life.” These people have realized that some of

their experiences online are impacting their personal lives to the point where they are no longer