2018

GLOBAL STUDY ON HOMICIDE

Gender-related killing of women and girls

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME

Vienna

GLOBAL STUDY ON HOMICIDE

Gender-related killing of women and girls

2018

Thegender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

2

DISCLAIMERS

© United Nations, November 2018. All rights reserved worldwide.

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form

for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from

the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) would appreciate

receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source.

Suggested citation: UNODC, Global Study on Homicide 2018 (Vienna, 2018)

No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNODC.

Applications for such permission, with a statement of purpose and intent of the

reproduction, should be addressed to the Research and Trend Analysis Branch of UNODC.

DISCLAIMER

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or

policies of UNODC or contributory organizations, nor does it imply any endorsement.

Comments on the report are welcome and can be sent to:

Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

PO Box 500

1400 Vienna

Austria

Tel: (+43) 1 26060 0

Fax: (+43) 1 26060 5827

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

3

Preface

Homicide represents the most extreme form of violence against women, a lethal act on a continuum of

gender-based discrimination and abuse.

As this research shows, gender-related killings of women and girls remain a grave problem across regions,

in countries rich and poor. While the vast majority of homicide victims are men, killed by strangers, women

are far more likely to die at the hands of someone they know.

Women killed by intimate partners or family members account for 58 per cent of all female homicide

victims reported globally last year, and little progress has been made in preventing such murders. Targeted

responses are clearly needed.

This booklet – part of the forthcoming Global Study on Homicide by the United Nations Office on Drugs and

Crime (UNODC) – is being released on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women

2018 to raise awareness, increase understanding and inform action.

It is also a call for Governments to help us shed further light on these challenges by collecting the needed

data and reporting on all forms of gender-based violence.

UNODC remains committed to supporting Member States to strengthen evidence-based policies and

criminal justice responses that can prevent and end violence against women and gender-related killings.

Yury Fedotov

Executive Director, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

4

Acknowledgements

Gender-related killing of women and girls was prepared by the Research and Trend Analysis Branch,

Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, under the

supervision of Jean-Luc Lemahieu, Director of the Division, and Angela Me, Chief of the Research and Trend

Analysis Branch.

General coordination and content overview

Angela Me

Andrada-Maria Filip

Marieke Liem

Analysis and drafting

Andrada-Maria Filip

Jonathan Gibbons

Marieke Liem

Kristiina Kangaspunta

Data management and estimates production

Enrico Bisogno

Diana Camerini

Sarika Dewan

Michael Jandl

Alexander Kamprad

Mateus Rennó Santos

Graphic design and production

Anja Korenblik

Suzanne Kunnen

Kristina Kuttnig

Administrative support

Iulia Lazar

Review and comments

Gender-related killing of women and girls benefited from the expertise of and invaluable contributions

from UNODC colleagues in all divisions and field offices. Particular thanks are owed to the Justice Section

of the Division of Operations and the Gender Team at the Office of the Executive Director.

Cover drawing © Yasser Rezahi; photo of artwork Fabian Rettenbacher.

The research for this study was made possible by the generous contribution of Sweden.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

5

Contents

Preface ................................................................................................................................................. 3

Contents ............................................................................................................................................... 5

Scope of the study ................................................................................................................................ 7

Introduction to the concept of gender-related killing of women and girls .............................................. 8

Key findings ........................................................................................................................................ 10

Intimate partner/family-related killing of women and girls: scale of the problem ................................ 13

Scale of the problem in numbers of victims .............................................................................................13

Scale of the problem in homicide rates ....................................................................................................13

Scale of the problem in shares of all women murdered ...........................................................................17

Female burden of intimate partner/family-related homicide ..................................................................18

Male and female rates of intimate partner/family-related homicide ......................................................19

Male and female rates of intimate partner homicide ..............................................................................21

The context of gender-related killing of women and girls ........................................................................22

Defining and understanding gender-related killing of women and girls ................................................ 24

Clustering gender-related killings of women and girls into different forms ............................................29

Perpetrators of intimate partner killings of women and girls ............................................................... 38

Victim and perpetrator characteristics .....................................................................................................38

Motives of perpetrators of intimate partner killings of women and girls ................................................39

Link between lethal and non-lethal violence against women ............................................................... 41

Criminal justice and policy responses to gender-related killing of women and girls .............................. 47

International responses ............................................................................................................................47

National responses ...................................................................................................................................48

Conclusions and Policy Implications .................................................................................................... 55

Annex ................................................................................................................................................. 57

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

7

Scope of the study

This study gives an overview of the scope of gender-related killing of women and girls. It provides in-depth

analysis of killings perpetrated within the family sphere and examines forms of gender-related killings

perpetrated outside the family sphere, such as the killing of women in conflict and the killing of female sex

workers. The study explores the scale of intimate partner/family-related killings of women and girls, and

describes different forms of gender-related killings of women. It also looks at the characteristics of the

perpetrators of intimate partner killings, the link between lethal and non-lethal violence against women,

and the criminal justice response.

The availability of data on intimate partner/family-related homicide means that such killings of females are

analysed in greater depth than other forms of “femicide”

1

and that the analysis focuses on how women

and girls are affected by certain norms, harmful traditional practices and stereotypical gender roles.

Although other forms of gender-related killing of women and girls are described, such as female infanticide

and the killing of indigenous or aboriginal women, given severe limitations in terms of data availability,

only literature-based evidence is provided.

The data presented in this study are based on homicide statistics produced by national statistical systems

in which the relationship between the victim and perpetrator or the motive is reported. While the

disaggregation of homicide data at country level has improved over the years, regional and global estimates

are based on a limited number of countries, with Africa and Asia accounting for most of the gaps.

……………..

1

Throughout this study the word “femicide” is written with quotation marks when it refers to a concept that is not clearly defined and

covers acts subject to a certain degree of interpretation. Femicide is written without quotation marks when referring to countries in Latin

America that have defined this concept in their national legislation.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

8

Introduction to the concept of gender-related killing

of women and girls

The focus of this study is on the killing of women and girls as a result of gender norms. Among the many

documents that draw attention to the alarming proportions reached by this phenomenon in all its different

manifestations, the 2013 United Nations General Assembly resolution on “Taking action against gender-

related killing of women and girls” is noteworthy.

2

Some national Governments, international organizations, academics and advocates of women’s rights use

the term “femicide” to refer to this problem. The notion of gender-related killing, or “femicide”, requires

an understanding of which acts are gender related; something that is subject to a certain degree of

interpretation. For example, in many cases there is a continuum of (intimate partner) violence that

culminates in the killing of women even when perpetrators have no specific (misogynistic) motives.

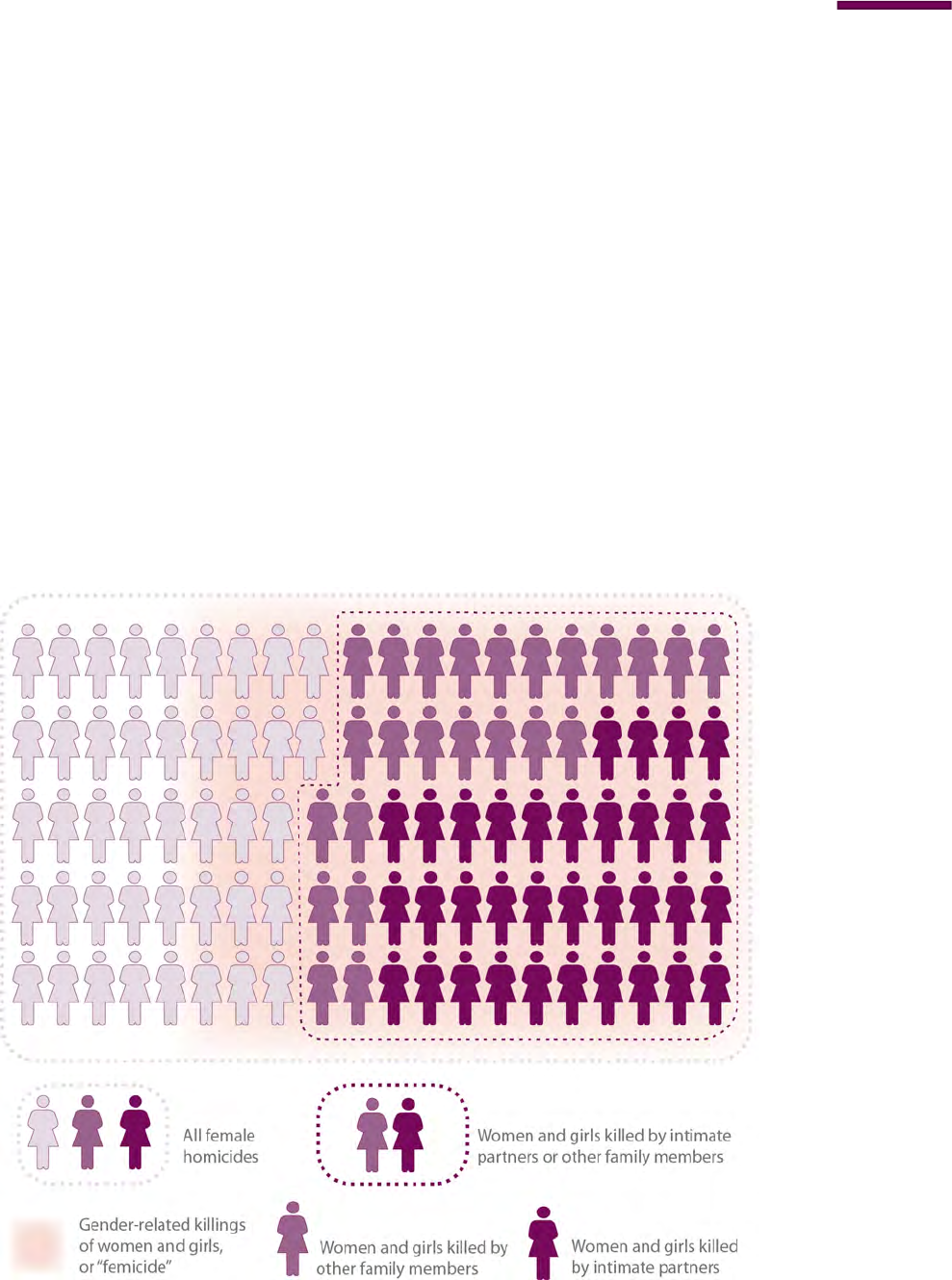

Nevertheless, some aspects of gender-related killing of women are indisputable, one being that this type

of homicide is part of female homicide, yet not all female homicides are gender related. Therefore, only a

specific, if considerable, share can be labelled “gender-related killings of women and girls”, i.e. “femicide”.

Gender-related killings of women and girls are committed in a variety of contexts and through different

mechanisms. In broader terms, such killings can be divided into those perpetrated within the family and

those perpetrated outside the family sphere. Data availability at regional and global level show that the

vast majority of cases of this type of crime fall into the first category.

Gender-related killing of women and girls is analysed in this study using the indicator for intimate

partner/family-related homicide. This provides a concept that covers most gender-related killings of

women, is comparable and can be aggregated at global level. Other existing national data labelled as

“femicide” are not comparable as countries use different legal definitions of this concept when collecting

……………..

2

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/191 specifically states: “Deeply concerned that the global prevalence of different

manifestations of the gender-related killing of women and girls is reaching alarming proportions, Concerned about violent gender-

related killing of women and girls, while recognizing efforts made to address that form of violence in different regions, including in

countries where the concept of femicide or feminicide has been incorporated into national legislation, draws attention to the alarming

proportions reached by this phenomenon in all its different manifestations. The resolution also noted that gender-related killing of

women and girls has been criminalized in some countries as “femicide” or “feminicide” and has been incorporated as such into

national legislation in those countries.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

9

data. Where data are available, however, it is clear that intimate partner/family-related homicide covers

most of the killings categorized as “femicide” and is a good fit for analysing trends in the latter.

UNODC collects data from Member States on intimate partner/family-related homicide as a proxy for

gender-related killings of women and the broad concept evolving around the notion of “femicide”. This

indicator covers female victims of homicide perpetrated by current or former intimate partners, or other

family members.

3

General sex-disaggregated homicide data are collected through regular UNODC data

collection on crime. Using the framework of the International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes

(ICCS), homicide data can be categorized and analysed to define gender-related killings and quantify

intimate partner/family-related homicide.

4

While the majority of intentional homicide victims are male, the majority of the victims of intimate

partner/family-related homicide are women. Therefore, understanding the extent and patterns of the

killing of women and girls requires the dedicated analysis of intimate partner/family-related homicide

explored in this study.

……………..

3

UNODC collects data on intimate partner/family-related homicide through the Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of the Criminal

Justice System.

4

The ICCS disaggregates intentional homicide according to the relationship between victims and perpetrators. Victims of intimate

partner homicide include those killed by a current or former intimate partner or spouse. Victims of intimate partner/family-related

homicide also include those killed by a blood relative, household member or relative by marriage or adoption. More information

available at http://www.unodc.org/documents/ data-and-analysis/statistics/crime/ICCS/Gender_and_the_ICCS.pdf.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

10

Key findings

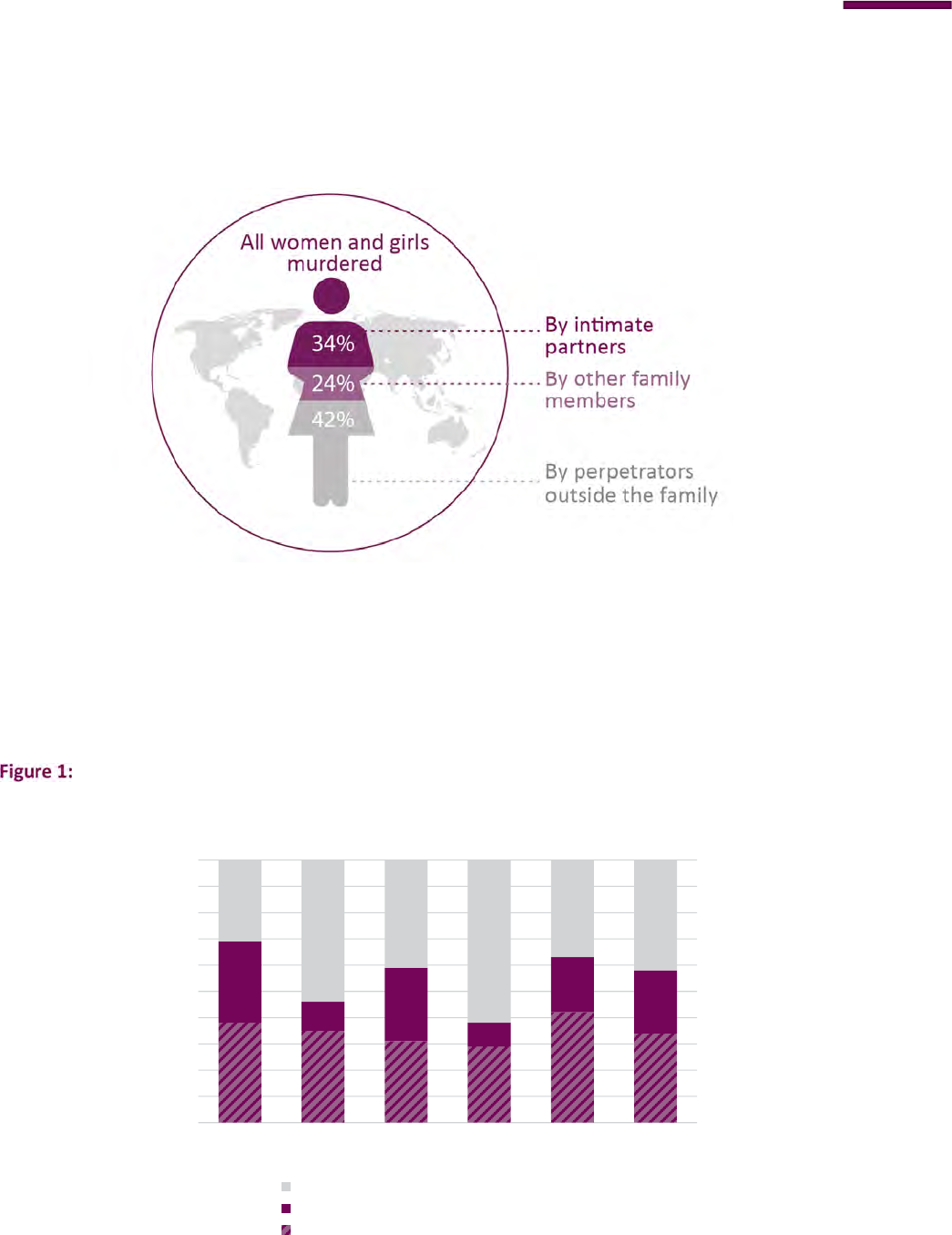

A total of 87,000 women were intentionally killed in 2017. More than half of them (58 per cent) ̶ 50,000 ̶

were killed by intimate partners or family members, meaning that 137 women across the world are killed

by a member of their own family every day. More than a third (30,000) of the women intentionally killed

in 2017 were killed by their current or former intimate partner ̶ someone they would normally expect to

trust.

Based on revised data, the estimated number of women killed by intimate partners or family members in

2012 was 48,000 (47 per cent of all female homicide victims). The annual number of female deaths

worldwide resulting from intimate partner/family-related homicide therefore seems be on the increase.

The largest number (20,000) of all women killed worldwide by intimate partners or family members in 2017

was in Asia, followed by Africa (19,000), the Americas (8,000) Europe (3,000) and Oceania (300). However,

with an intimate partner/family-related homicide rate of 3.1 per 100,000 female population, Africa is the

region where women run the greatest risk of being killed by their intimate partner or family members,

while Europe (0.7 per 100,000 population) is the region where the risk is lowest. The intimate

partner/family-related homicide rate was also high in the Americas in 2017, at 1.6 per 100,000 female

population, as well as Oceania, at 1.3, and Asia, at 0.9.

Even though the largest number of women and girls are killed by intimate partners or family members

in Asia, they run the greatest risk of being killed by an intimate partner or family member in Africa.

The regions with the largest number of females killed purely by intimate partners (not including other

family members) in 2107 were Asia and Africa (11,000 each), followed by the Americas (6,000), Europe

(2,000) and Oceania (200).

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

11

Africa was also the region with the highest rate of females killed purely by intimate partners in 2017 (1.7

per 100,000 female population). The Americas had the second-highest rate (1.2), Oceania the third (0.9),

Europe the fourth (0.6) and Asia the fifth-highest rate (0.5 per 100,000 female population).

The global rate of female total homicide in 2017 was estimated to be 2.3 per 100,000 female population,

the global female intimate partner/family-related homicide rate was 1.3, while the female intimate partner

homicide rate was estimated at 0.8 per 100,000 female population.

More than two thirds of all women (69 per cent) killed in Africa in 2017 were killed by intimate partners or

family members, while more than a third (38 per cent) of women were killed by intimate partners or family

members in Europe. Oceania accounts for the largest share of all the regions in terms of women killed

exclusively by intimate partners, at 42 per cent, while Europe accounts for the lowest, at 29 per cent.

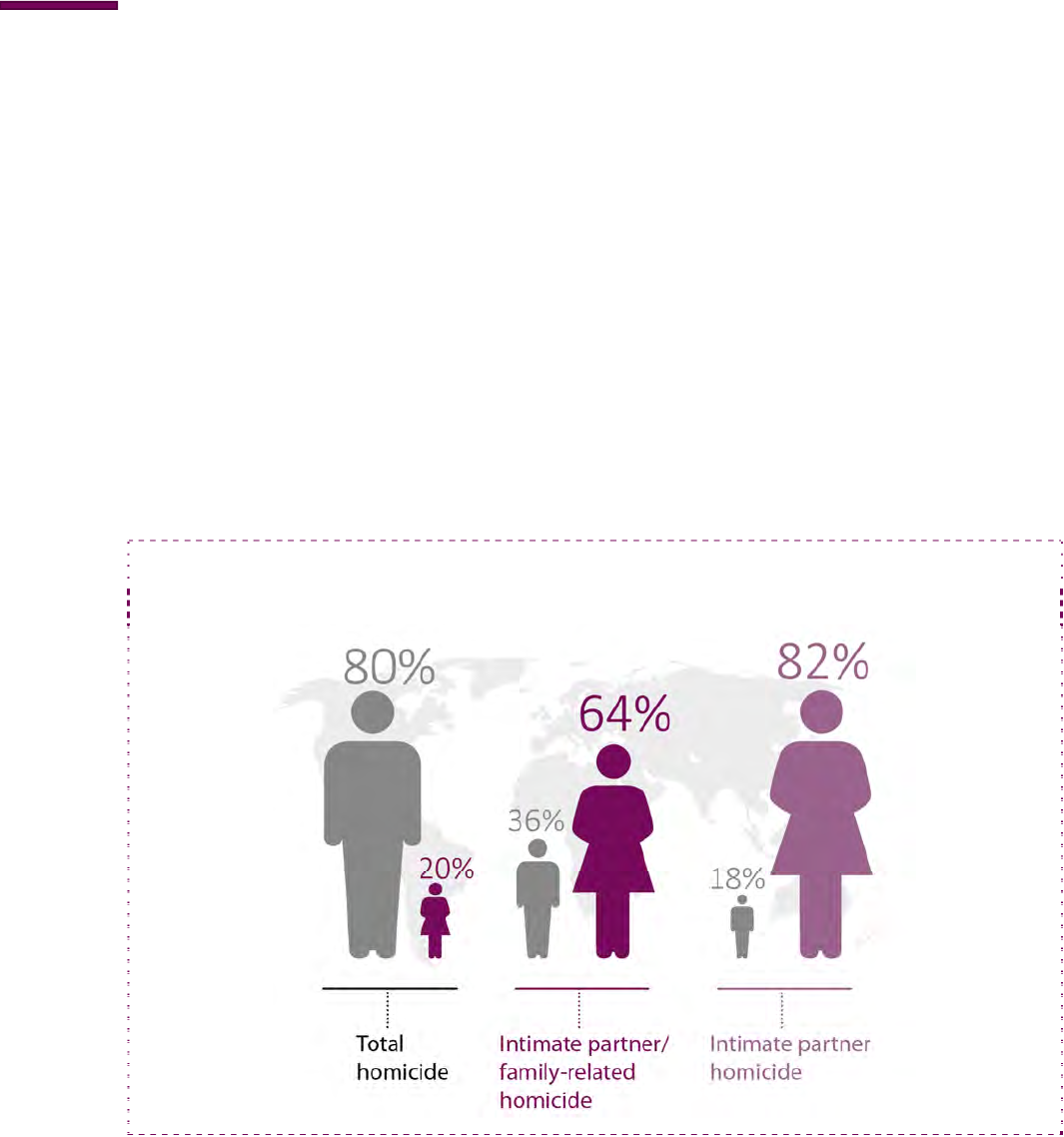

Only one out of every five homicides at global level is perpetrated by an intimate partner or family member,

yet women and girls make up the vast majority of those deaths. Victim/perpetrator disaggregations reveal

a large disparity in the shares attributable to male and female victims of homicides committed by intimate

partners or family members: 36 per cent male versus 64 per cent female victims.

Women also bear the greatest burden in terms of intimate partner violence. The disparity between the

shares of male and female victims of homicide perpetrated exclusively by an intimate partner is

substantially larger than of victims of homicide perpetrated by intimate partners or family members:

roughly 82 per cent female victims versus 18 per cent male victims.

Althoughwomenandgirlsaccountforafarsmallershareoftotalhomicidesthanmen,theybearbyfarthe

greatestburdenofintimatepartner/family‐relatedhomicide,andintimatepartnerhomicide.

These findings show that even though men are the principal victims of homicide globally, women continue

to bear the heaviest burden of lethal victimization as a result of gender stereotypes and inequality. Many

of the victims of “femicide” are killed by their current and former partners, but they are also killed by

fathers, brothers, mothers, sisters and other family members because of their role and status as women.

The death of those killed by intimate partners does not usually result from random or spontaneous acts,

but rather from the culmination of prior gender-related violence. Jealousy and fear of abandonment are

among the motives.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

12

Through the indicator “female victims of homicide perpetrated by intimate partners or family members”,

this study quantifies a significant share of all gender-related killings of women and girls perpetrated

globally, including forms that are prevalent across certain regions, such as dowry and honour killing. Given

the lack of data, it is not possible to quantify the number of gender-related killings outside the family, but

the study describes their different manifestations and provides examples where information is available.

The information available shows that, other than gender-related killings in conflict settings, gender-related

killings of women and girls outside the family are relatively rare in comparison to killings perpetrated by

intimate partners or other family members.

Countries have taken action to address violence against women and gender-related killings in different

ways, by adopting legal changes, early interventions and multi-agency efforts, as well as creating special

units and implementing training in the criminal justice system. Countries in Latin America have adopted

legislation that criminalizes femicide as a specific offence in their penal codes. Yet there are no signs of a

decrease in the number of gender-related killings of women and girls.

This study highlights what more can be done to prevent those killings. A more comprehensive range of

coordinated services needs to be provided by police, criminal justice systems, health and social services.

Moreover, in order to prevent and tackle gender-related killing of women and girls, men need to be

involved in efforts to combat intimate partner violence/family-related homicide and in changing cultural

norms that move away from violent masculinity and gender stereotypes.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

13

Intimate partner/family-related killing of women and

girls: scale of the problem

Scale of the problem in numbers of victims

The lethal victimization of women within the family sphere is encountered in all regions and countries.

UNODC estimates that the deaths of women and girls resulting from intentional homicide perpetrated by

an intimate partner or family member

5

amounted to a global total of 50,000 in 2017.

6

An improvement in

the coverage of gender-disaggregated country data has led UNODC to reevaluate the 2012 figure published

in the previous edition of the Global Study on Homicide to 48,000. The number of female deaths resulting

from intimate partner or family/related homicide may therefore have increased slightly.

7

Given that the total number of deaths of women and girls worldwide resulting from all forms of intentional

homicide amounted to 87,000 in 2017, more than half (58 per cent) of all female victims of intentional

homicide, or 137 every day, were actually killed by a member of their own family. The number of women

killed purely by their intimate partners (not including those killed by family members) was 30,000, meaning

that more than one third (34 per cent) of all women and girls intentionally killed worldwide, or 82 every

day, are killed by someone whom they would normally trust and expect to care for them.

Scale of the problem in homicide rates

The number of victims is only one way of looking at the toll that intimate partner/family-related homicide

takes on women. Looking at the homicide rate per 100,000 female population offers a different

perspective. For example, in absolute numbers, the largest number of women killed by an intimate partner

or family member in 2017 was in Asia (20,000), by far the most populous of the five regions. However, at

3.1 per 100,000 female population, the highest rate of intimate partner/family-related homicide was in

Africa. Thus, while fewer women are killed by their intimate partner or family members in Africa than in

Asia, women are actually at a higher risk of being killed by their intimate partner or family members in

Africa. Women are also most at risk of being killed by their intimate partners (not including other family

members) in Africa (1.7 per 100,000 female population) and the Americas (1.2), while they are least at risk

in Oceania (0.9), Europe (0.6) and Asia (0.5).

Estimated at 1.3 per 100,000 population in 2017, although slightly lower than in 2012, when it stood at 1.4

per 100,000 population, the female intimate partner/family-related homicide can be considered stable at

global level. However, the female intimate-partner/family-related homicide rate not only has variations in

the prevalence of homicide across regions but also between countries within those regions (see box 1).

These variations show that, in general, countries with relatively low female total homicide rates tend to

have a relatively larger share of female intimate partner/family-related homicides, whereas in countries

with relatively high female total homicide rates, the share of female intimate partner/family-related

homicides is relatively smaller. This is because more women are killed outside the family sphere, although

the actual intimate partner/family-related homicide rate may still be relatively high.

……………..

5

In heterosexual relationships, women are killed by a male partner, whereas those killed by family members are killed by both sexes.

6

When provided by countries, 2017 data has been used throughout this study. Otherwise data refer to the latest available year.

7

The Global Study on Homicide 2013 estimated that 43,600 women were killed in 2012 by their family members or intimate partners.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

14

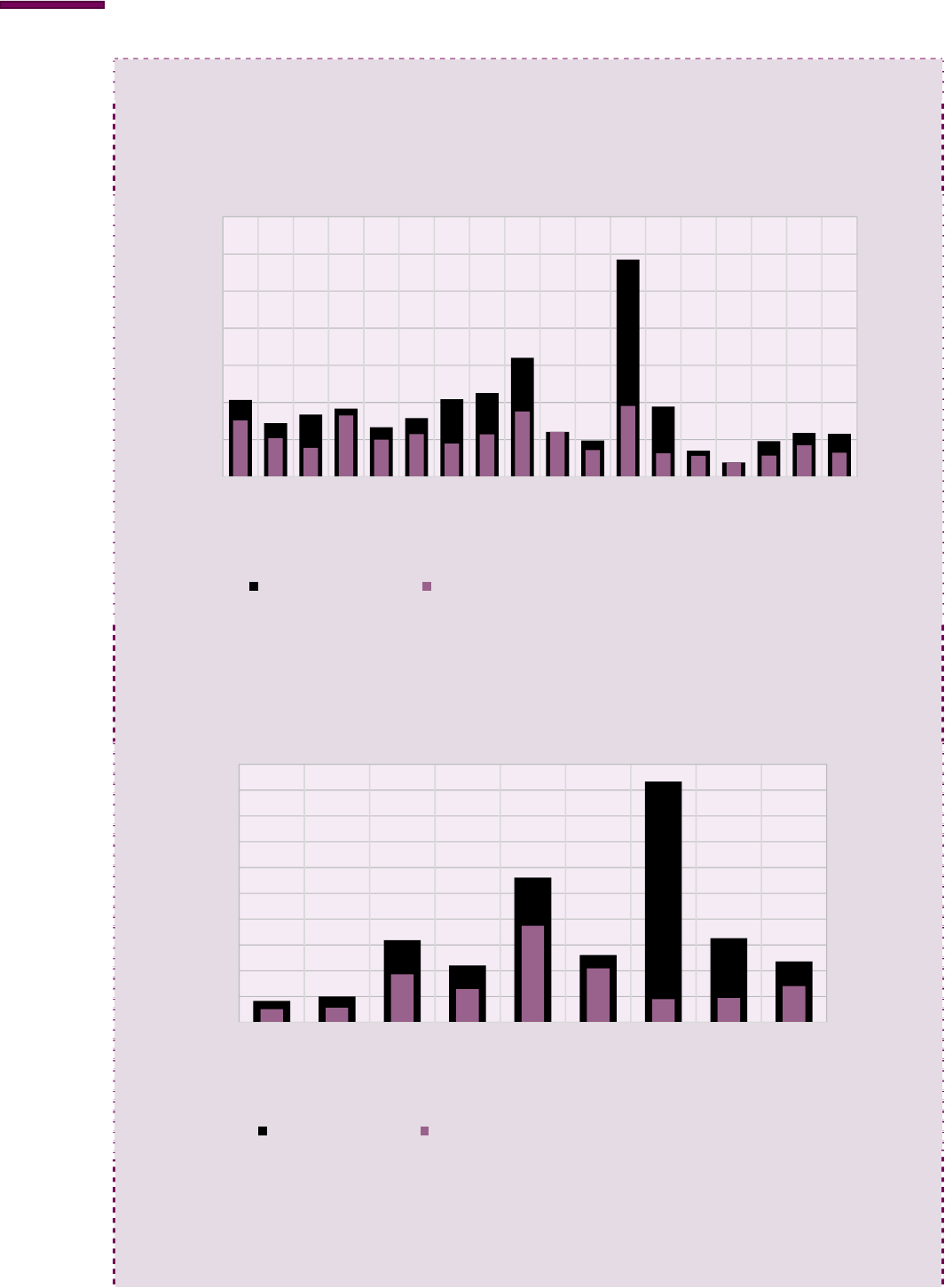

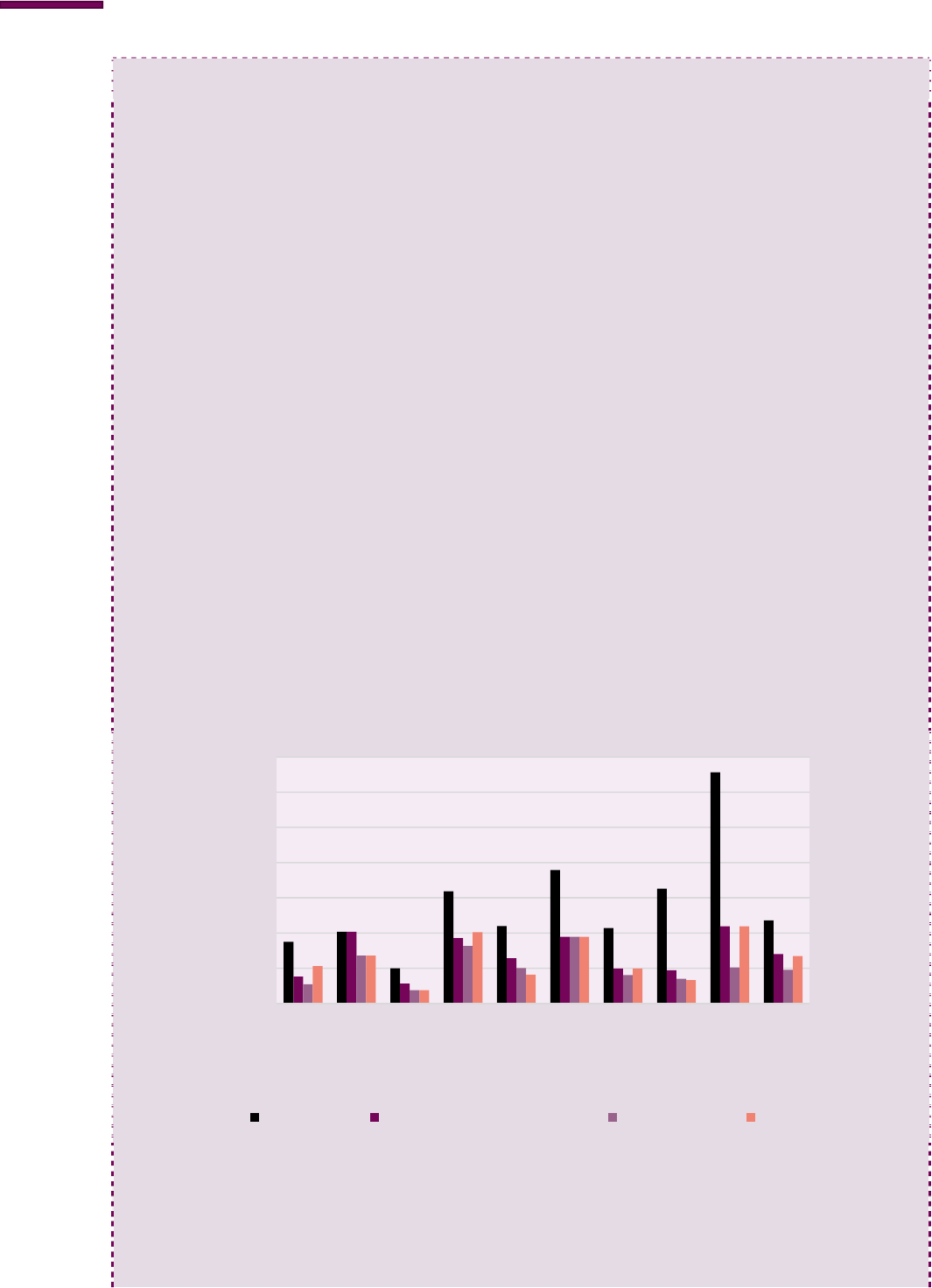

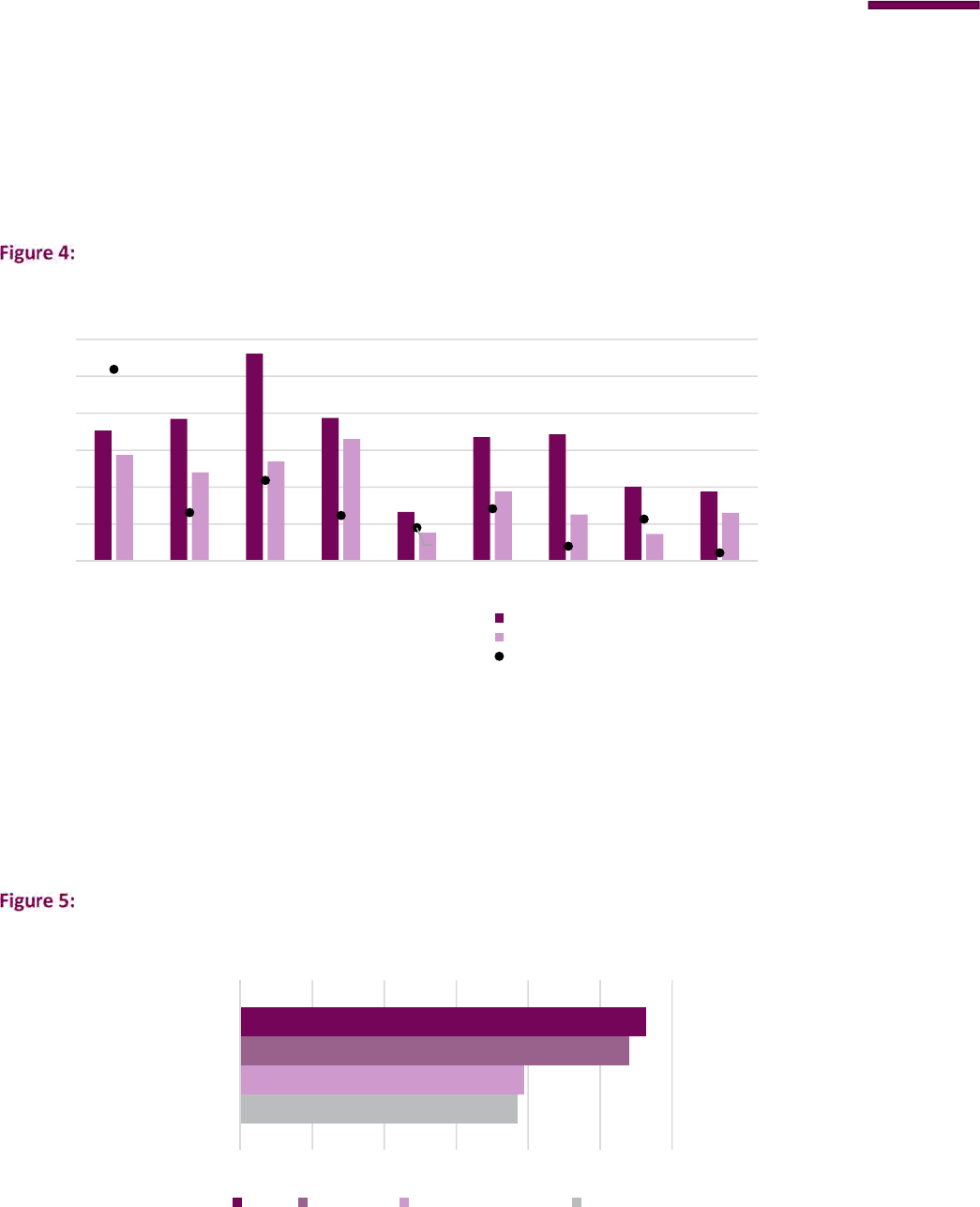

BOX 1: Female total homicide and intimate partner/family-related homicide in

selected countries

Rates of female total homicide and of intimate partner/family-related homicide, selected countries in

Europe (2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics.

Rates of female total homicide and of intimate partner/family-related homicide, selected countries in

the Americas (2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics; Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

1.0

0.7

0.8

0.9

0.7

0.8

1.0

1.1

1.6

0.6

0.5

2.9

0.9

0.4

0.2

0.5

0.6

0.6

0.8

0.5

0.4

0.8

0.5

0.6

0.4

0.6

0.9

0.6

0.4

1.0

0.3

0.3

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.3

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

Albania

Austria

Bosnia and

Herzegovina

Croatia

Czechia

Finland

France

Germany

Hungary

Iceland

Italy

Lithuania

Montenegro

Netherlands

Slovenia

Spain

Switzerland

United Kingdom

(Scotland)

Rate per 100,000 female population

Total homicide Intimate partner/family-related homicide

0.8

1.0

3.2

2.2

5.6

2.6

9.3

3.3

2.4

0.5

0.6

1.9

1.3

3.7

2.1

0.9

0.9

1.4

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

7.0

8.0

9.0

10.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

7.0

8.0

9.0

10.0

Canada

Chile

Dominican

Republic

Ecuador

Grenada

Guyana

Jamaica

Peru

Uruguay

Rate per 100,000 female population

Total homicide Intimate partner/family-related homicide

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

15

Rates of female total homicide and of intimate partner/family-related homicide, selected countries in

Asia and Oceania (2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics.

Data on the killing of women perpetrated exclusively by intimate partners (not including other family

members) is even harder to come by than data on women killed by intimate partners or family members,

but where data are available (see box 2) the picture is similar to that relating to intimate-partner/family-

related homicide, as mentioned in the previous paragraph.

BOX 2: Female total homicide and intimate partner homicide in selected

countries

Rates of female total homicide and of intimate partner homicide, selected countries, Europe (2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics.

0.7

1.8

0.9

2.6

0.4

0.6

0.7

0.6

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

Australia Azerbaijan Cyprus Mongolia

Rate per 100,000 female population

Total homicide

Intimate partner/family-related homicide

1.0

0.8

0.9

0.7

0.8

1.0

1.1

1.6

0.6

0.5

2.9

0.4

0.2

0.5

0.6

0.2

0.6

0.7

0.1

0.5

0.3

0.4

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.2

0.5

0.2

0.0

0.2

0.3

0.1

0.1

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

Albania

Bosnia and

Herzegovina

Croatia

Czechia

Finland

France

Germany

Hungary

Iceland

Italy

Lithuania

Netherlands

Slovenia

Spain

Switzerland

Northern Ireland

United Kingdom

(Scotland)

Rate per 100,000 female population

Total homicide Intimate partner homicide

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

16

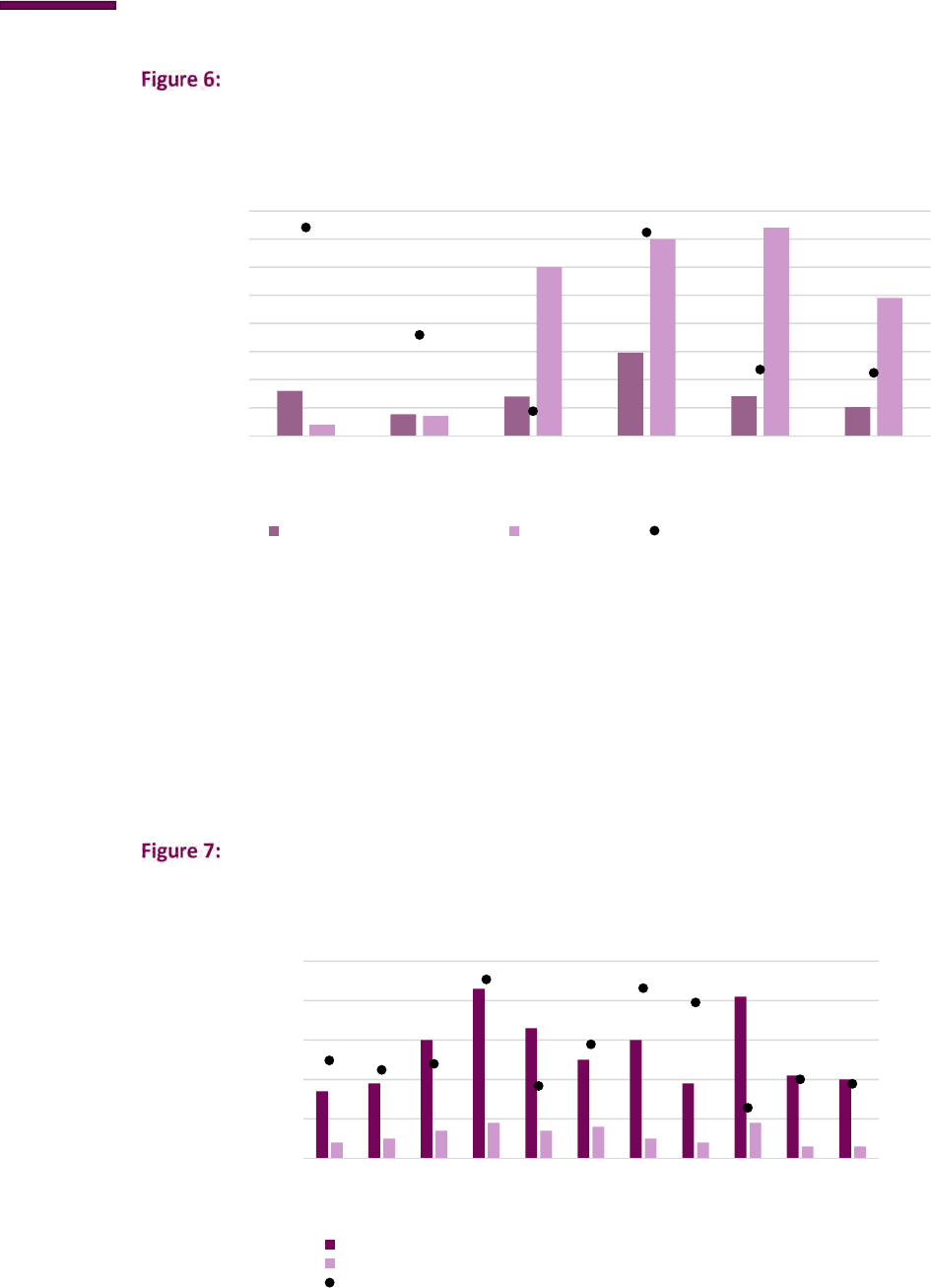

Rates of female total homicide and of intimate partner homicide, selected countries, Latin America and

the Caribbean (2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics.

Rates of female total homicide and of intimate partner homicide, selected countries, Asia (2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics.

8.1

0.8

1.0

3.2

2.2

2.6

9.3

3.3

5.8

2.4

2.7

0.3

0.4

1.6

1.0

2.1

0.9

0.7

4.3

1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

7.0

8.0

9.0

10.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

7.0

8.0

9.0

10.0

Belize

Canada

Chile

Dominican

Republic

Ecuador

Guyana

Jamaica

Peru

Suriname

Uruguay

Rate per 100,000 female population

Total homicide

Intimate partner homicide

0.8

2.6

0.2

0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

Jordan Mongolia

Rate per 100,000 female population

Total homicide

Intimate partner homicide

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

17

Scale of the problem in shares of all women murdered

While almost six out of every ten women (58 per cent) intentionally killed worldwide are actually murdered

by an intimate partner or other family member, there are marked disparities in this share across all the

regions.

In four of the six regions, the share is very large, making the home the most likely place for a woman to be

killed. At the upper extreme, more than two thirds of all women (69 per cent) intentionally killed in Africa

in 2017 were killed by intimate partners or other family members, while the region with the smallest share

of women killed by intimate partners or other family members was Europe (38 per cent). Oceania

accounted for the largest share of all the regions in terms of women killed exclusively by intimate partners,

at 42 per cent, while Europe accounted for the lowest (29 per cent).

Female victims of intimate partner/family-related homicide and of intimate partner

homicide as a percentage of female total homicide victims, by region (2017)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics (estimated).

Note: Any differences between the counts and percentages presented are because of roundings.

38%

35%

31%

29%

42%

34%

69%

46%

59%

38%

63%

58%

Africa Americas Asia Europe Oceania Global

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Percentage of total victims of female homicide

Other female homicide

Intimate partner/family-related homicide

Intimate partner homicide

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

18

Female burden of intimate partner/family-related homicide

Although intimate partner/family-related homicide is the most important factor in understanding the

magnitude of female deaths resulting from intentional homicide, this form of homicide only accounts for a

relatively small proportion of all (male and female) homicides recorded globally. While still far too many,

fewer than one out of every five homicides (18 per cent) at global level were perpetrated by an intimate

partner or other family member in 2017. In terms of homicide perpetrated exclusively by an intimate

partner (not including other family members), the proportion was lower: roughly one out of every eight

(12 per cent) homicides.

At regional level, the portion of all homicides in 2017 caused by intimate partners or other family members

in Oceania (39 per cent), Asia and Europe (both 24 per cent) was significantly larger than the share of such

homicides in the other regions, particularly Africa and the Americas. In some countries in the Americas,

very high homicide rates are associated with crime (mainly organized crime), which means that the shares

of intimate partner/family-related homicide and of intimate partner homicide out of all homicides are

smaller than in other regions, although the number of victims is still high in comparative terms. With the

exception of Oceania, the disparity in the share of homicides caused by intimate partner or family members

and those caused purely by intimate partners is less marked between regions.

Although women and girls account for a far smaller share of total homicides than men, they bear by

far the greatest burden of intimate partner/family-related homicide, and intimate partner homicide.

At global level, men are around four times more likely than women to lose their lives as a result of

intentional homicide: gender-disaggregated data on homicide reveal that the shares attributable to male

and female victims remained very stable, with roughly 80 per cent of all homicides committed globally

attributable to male victims and 20 per cent to female victims.

Only one out of every five homicides at global level may be perpetrated by an intimate partner or family

member, yet women and girls make up the vast majority of those deaths. Victim/perpetrator

disaggregations reveal a large disparity in the shares attributable to male and female victims of homicide

committed by intimate partners or other family members: 36 per cent of victims were male, while 64 per

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

19

cent were female.

8

This represents an increase of 4 percentage points in the share of female victims of

intimate partner/family-related homicide since 2014.

Women also bear the greatest burden in terms of intimate partner homicide. The disparity between the

shares of male and female victims of homicide perpetrated exclusively by an intimate partner is

substantially larger than between male and female victims of homicide perpetrated by intimate partners

or family members, with an even greater share of female victims in the total number of homicides

committed: roughly 82 per cent were female victims while 18 per cent were male victims, a share that has

remained quite stable since 2012. Intimate partner violence continues to take a disproportionately heavy

toll on women.

Male and female rates of intimate partner/family-related

homicide

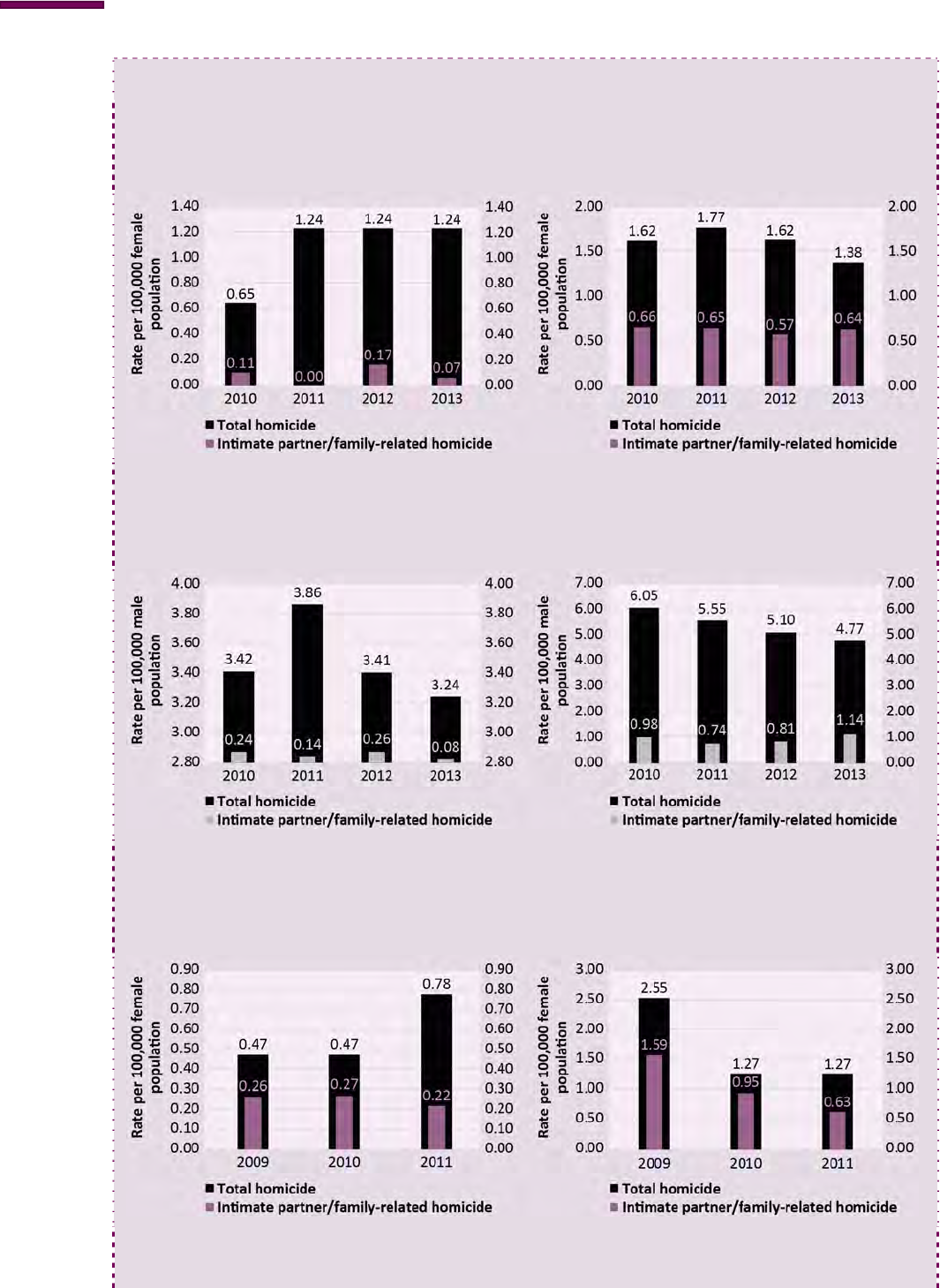

In terms of country examples of male and female rates of total homicide and intimate partner/family-

related homicide, because of existing limitations in the availability of data in countries in Africa and Asia,

victims of intimate partner/family-related homicide disaggregated by sex can only be analysed in a few

countries (see box 3). The picture shown in this sample is one in which intimate partner/family-related

homicide remains stable over time, despite changes in the overall homicide rate. These limited examples

also show that some countries may be an exception to the global pattern in which women are more likely

to be victims of intimate partner/family-related homicide than men. However, while both male and female

homicide is perpetrated within the domestic sphere, it is possible that the relationship between victims

and perpetrators is not recoded for all homicides. Progress has been made by countries in collecting sex-

disaggregated homicide data, yet advances made in collecting homicide data disaggregated by

victim/perpetrator relationship are still limited. There are therefore serious limitations in terms of data

availability for this indicator and, when reported, such figures may point towards an under-recording of

victims.

……………..

8

These findings are in line with those published in the Global Study on Homicide published by UNODC in 2011 and 2013, which also showed

that women were overwhelmingly represented in the share of victims of homicide committed by family members and intimate partners.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

20

BOX 3:

Male and female intimate partner/family-related homicide and total

homicide in selected countries

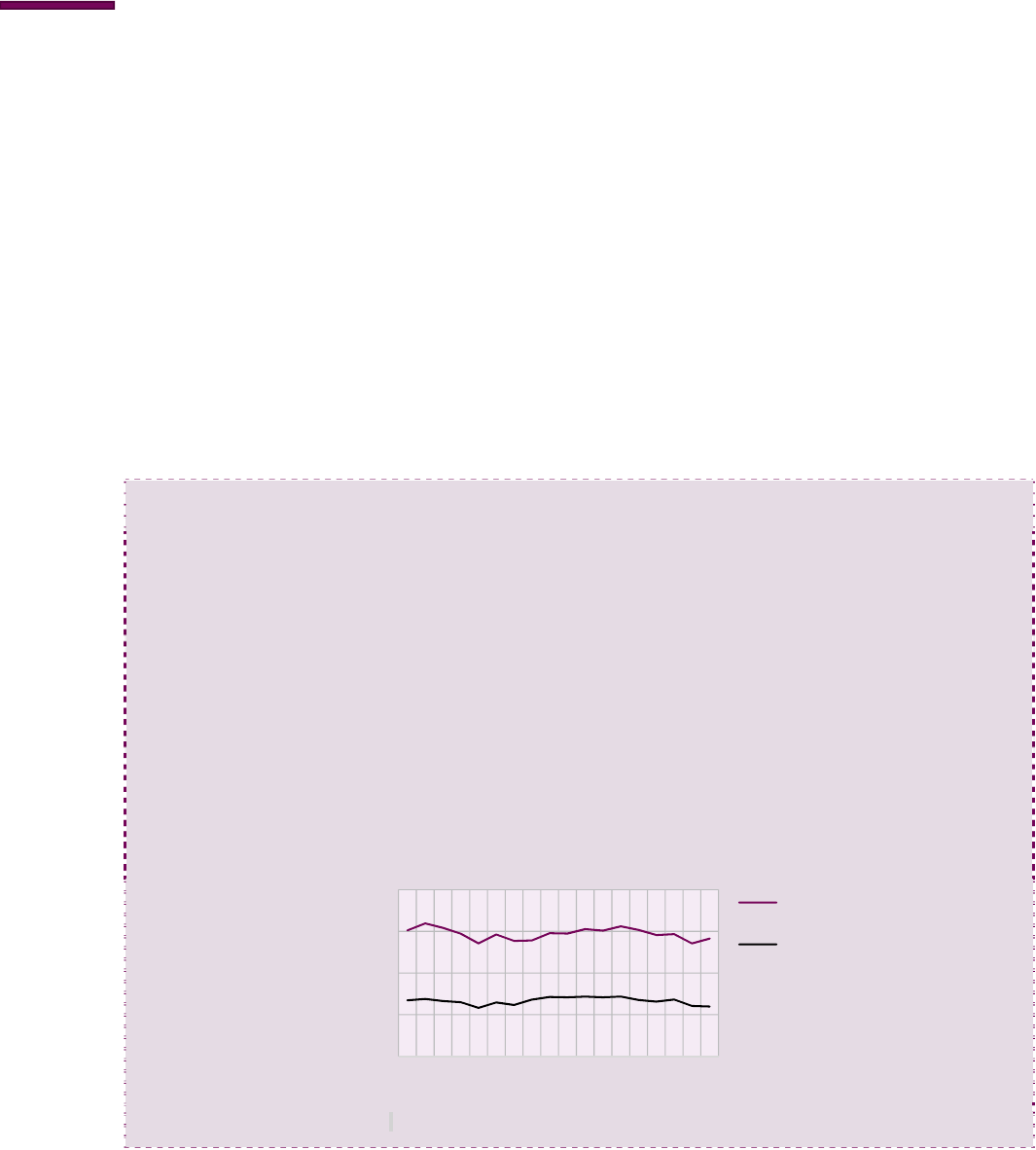

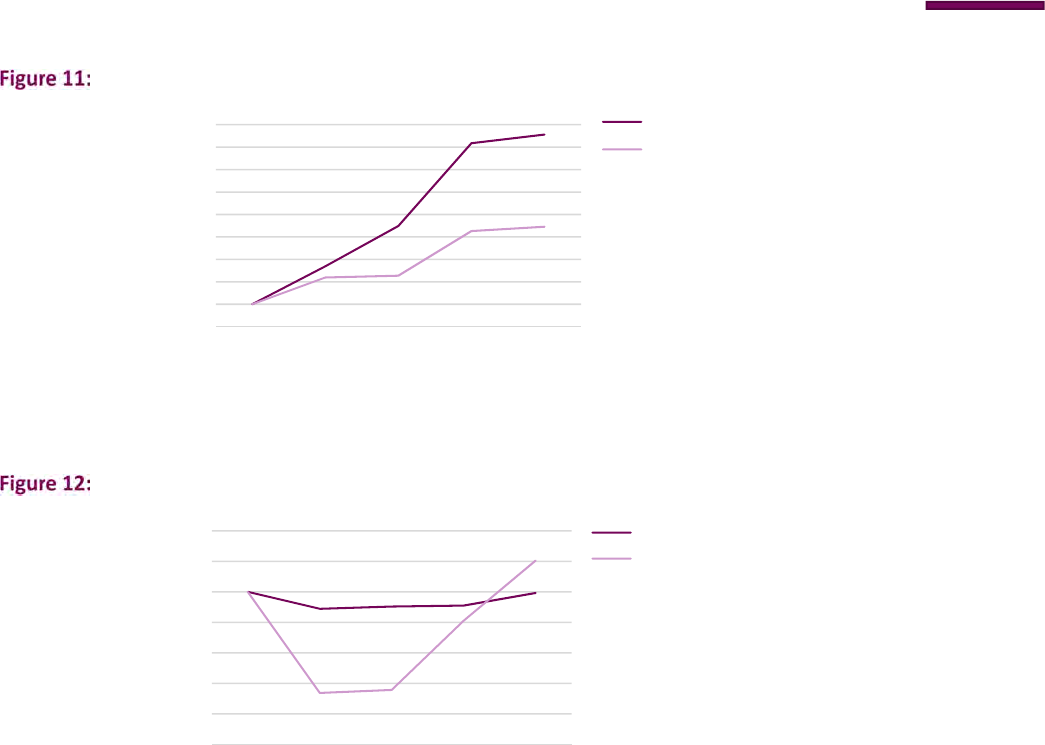

Rates of female intimate partner/family-related homicide and of total homicide, Armenia (left) and Sri

Lanka (right) (2010 ̶ 2013)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics.

Rates of male intimate partner/family-related homicide and of total homicide, Armenia (left) and Sri

Lanka (right) (2010 ̶ 2013)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics.

Rates of female intimate partner/family-related homicide and of total homicide, Egypt (left) and

Mauritius (right) (2009 ̶ 2011)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

21

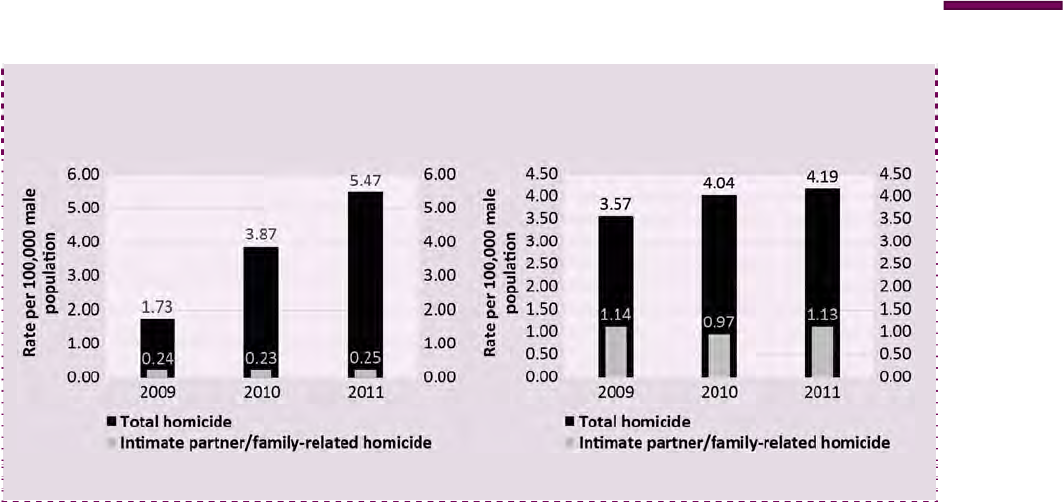

Rates of male intimate partner/family-related homicide and of total homicide, Egypt (left) and Mauritius

(right) (2009 ̶ 2011)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics.

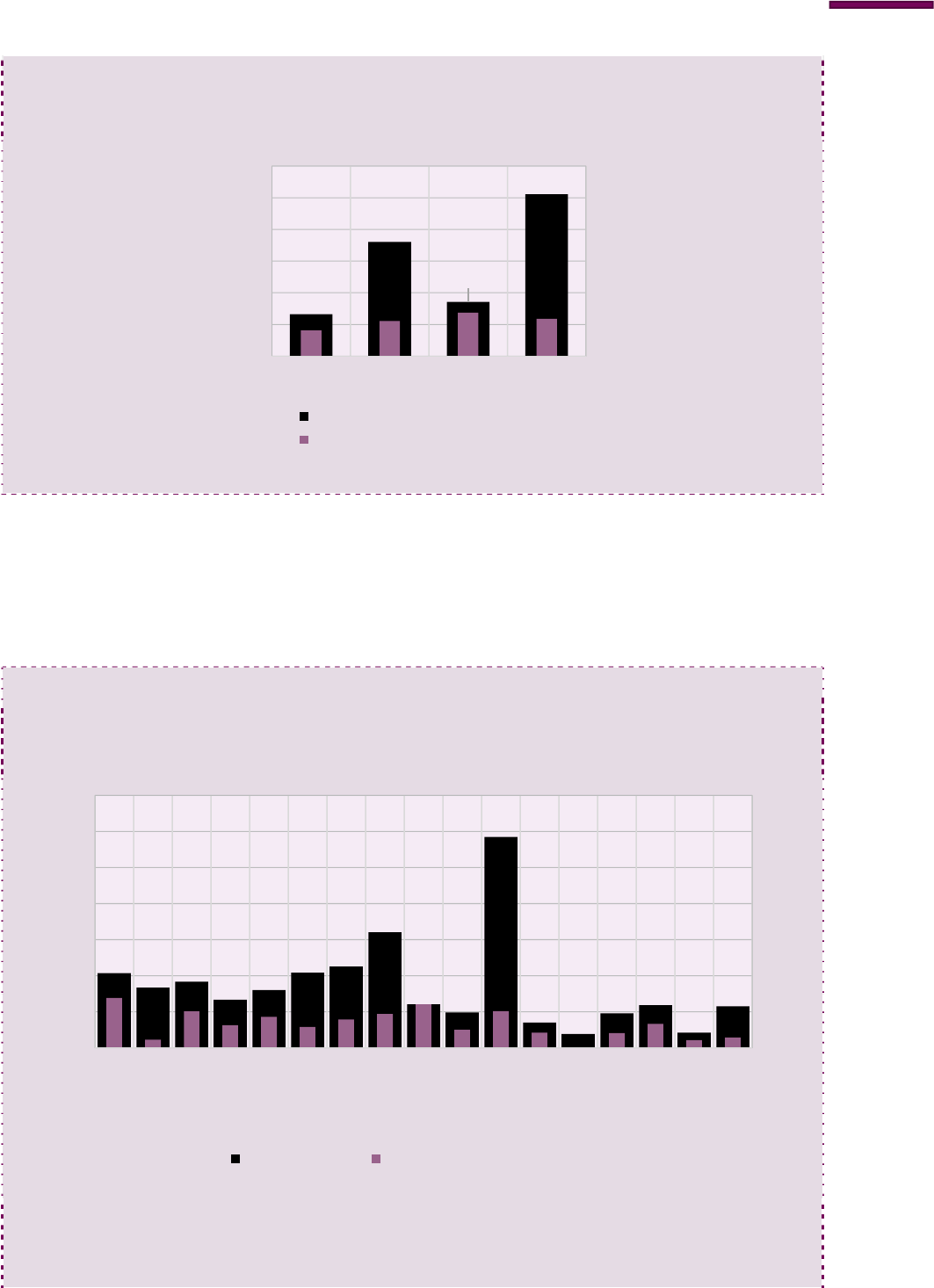

Male and female rates of intimate partner homicide

Although data availability on male and female rates of intimate partner homicide is very limited across

regions, it is possible to put those rates into perspective in a sample of European and Latin American

countries (see box 4). A substantial disparity is observable between these values across both regions, with

the female rate being much higher than the male rate. In Europe, the female intimate partner homicide

rate was, on average, four times higher than the male intimate partner homicide rate in 2016. As significant

as this may be, it is important to highlight the fact that these rates are very low when compared with overall

national homicide rates. In Latin America, the disparity was even larger, as the female intimate partner

homicide rate was five times higher than the male rate.

Asia, Europe and Oceania generally have low levels of homicide but the share of women among all homicide

victims tends to be higher than in regions with higher levels of homicide. This observation is in line with

the first of “Verkko’s laws”, the “static law”, which holds that the higher the level of homicide, the smaller

the share of female victims and perpetrators. In other words, in countries with low homicide rates the

difference between male and female homicide rates is smaller than in countries with high homicide rates.

9

……………..

9

Verkko, V., “Homicides and suicides in Finland and their dependence on national character”, Scandinavian Studies in Sociology, vol. 3

(Copenhagen, Gads Forlag, 1951).

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

22

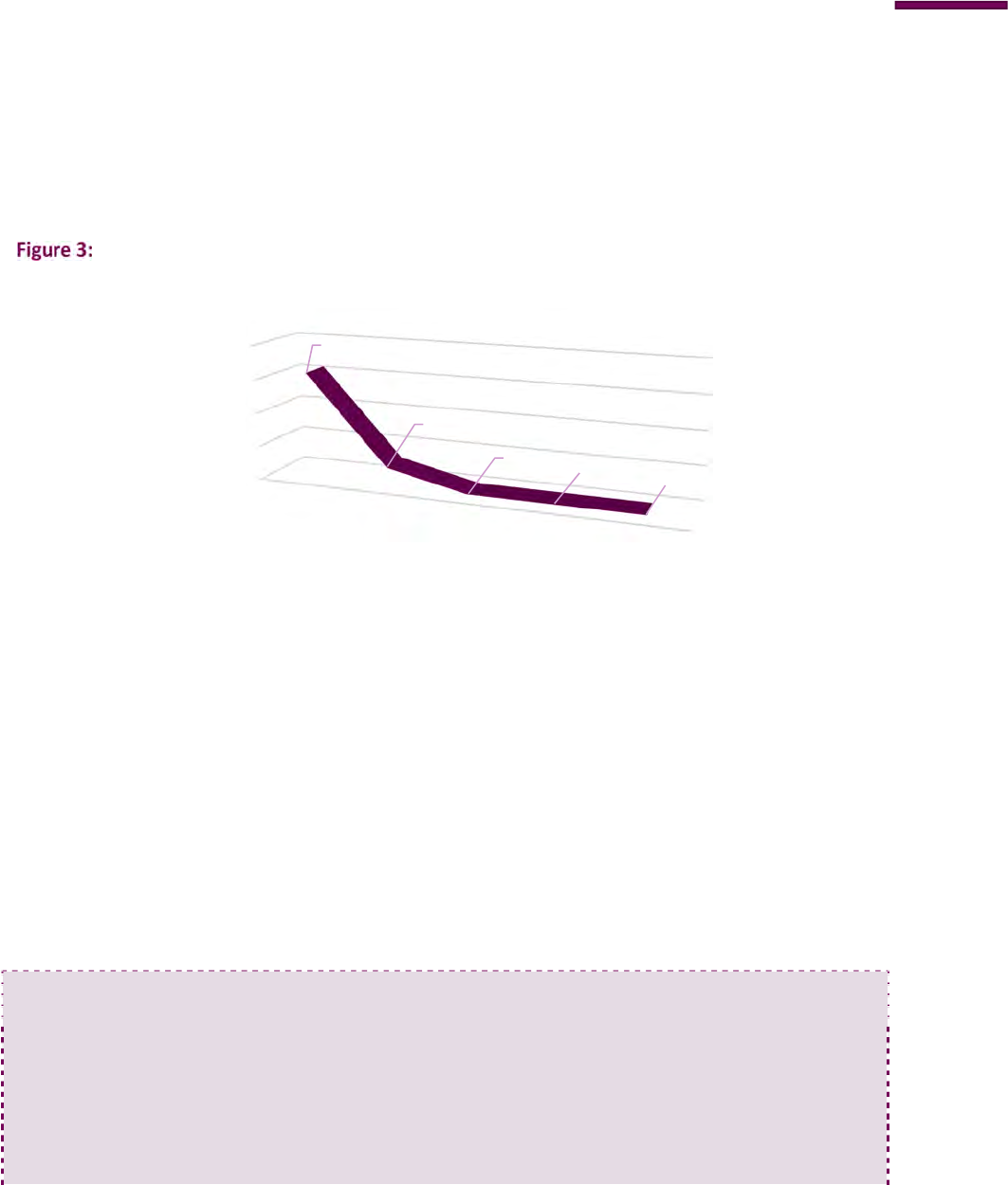

BOX 4: Male and female intimate partner homicide in selected countries

Intimate partner homicide rate, by sex, Europe (2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics.

Rate of intimate partner homicide, by sex, Latin America and the Caribbean (2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics.

The context of gender-related killing of women and girls

While the International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (ICCS) provides the framework for

recording homicide and crime data, according to the situational context, geographical location, date, time

and motive, very few countries release national data on the circumstances surrounding gender-related

killings of women and girls. Anecdotal information is available for very few countries. Reports from

Argentina

10

and Peru indicate that the majority of gender-related killings of women and girls, or femicide,

in those countries are perpetrated in large cities, usually the capital. In the case of Peru, the mechanism

……………..

10

Registro Nacional de Femicidios de la Justicia Argentina, Datos estadísticos del poder judicial sobre femicidios 2014-2016. Available at

https://www.csjn.gov.ar/om/femicidios.html.

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.5

0.2

0.2

0.0

0.2

0.1

0.1

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

Croatia

Finland

France

Hungary

Netherlands

Spain

Rate per 100,000 population

Female

Male

0.4

0.9

1.6

1.0

1.0

0.7

0.1

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.2

0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

Chile

Jamaica

Dominican

Republic

Ecuador

Uruguay

Peru

Rate per 100,000 population

Female

Male

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

23

for committing femicide is often asphyxiation or strangulation, stabbing, beating or shooting by firearm.

11

Over the period 2011-2014, the majority of gender-related killings in Peru occurred in the private sphere,

whether in the house occupied by the perpetrator and the victim, the house of the victim or the house of

the perpetrator.

12

……………..

11

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, “Homicidios en el Perú, contándolos uno a uno: 2011-2014” (Observatorio de Igualdad de Género de

América Latina y el Caribe, 2105), p. 37. Available at https://oig.cepal.org/es/documentos/homicidios-peru-contandolos-2011-2014-

feminicidio-ministerio-publico.

12

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, “Homicidios en el Perú, contándolos uno a uno 2011-2014”, p. 45.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

24

Defining and understanding gender-related killing

of women and girls

Two terms, “femicide” and “feminicide”, are widely used in relation to the concept of gender-related killing

of women and girls. The conventional understanding conveys the idea that hate crimes against women are

perpetrated by men simply because of the gender roles assigned to women.

The term “femicide” was coined in the literature several decades ago to define the gender-related

motivation associated with the killing of women and girls.

13

Although the term has attracted attention to

the extent that it is now used by some Governments and a wide range of stakeholders, at global level there

is no commonly agreed definition of what constitutes “femicide”. What is observable, however, is a

plurality of definitions stemming from different legal and sociological approaches, which indicate the

elements that may contribute to labelling a crime “femicide”. The following section provides an overview

of the sort of crimes that have been considered in the context of gender-related killing of women or

“femicide”.

The history of the term “femicide” goes back to the term coined in the 1970s,

14

which sought to raise

awareness of the violent deaths of women and referred to the killing of females by males because they are

females. Subsequently, “femicide” was defined in the first anthology on “femicide” published in 1992 as

“the misogynous killing of women by men motivated by hatred, contempt, pleasure, or a sense of

ownership over women, rooted in historically unequal power relations between women and men”. In the

past few decades, the term and its associated problem has been gaining recognition by academics, civil

society organizations, international organizations and regional organizations such as the European Union.

15

For example, a report by the United Nations Secretary General in 2006 referred to “femicide” as “the

gender-based murder of a woman” and “the murder of women because they are women”. The report

focused on certain settings and community contexts, such as intimate partner violence, armed conflict and

dowry disputes, in which those crimes were being perpetrated.

16

The report also highlighted certain

characteristics of such homicides, as well as the underlying gender inequality between men and women

that fuels them, thus illustrating the interrelationship between cultural norms and the use of violence in

the subordination of women.

17

In September 2018, the European Union and the United Nations launched

a joint programme aimed at tackling “femicide” in Latin America.

18

While men are usually considered to be the perpetrators of gender-related killings of women and girls, this

is not the case in all situations. Historically, the study of female victimization has been focused on intimate

partner killings perpetrated by men, as intimate partner killings account for a significant share of gender-

related killings of women and girls.

19

Nevertheless, it is important to bear in mind that in some instances

women can also be perpetrators of extreme gender-based violence against other women. For example, in

cases of honour killings, both male and female family members may be complicit.

Several theoretical approaches to gender-related killing of women and girls have emerged in contemporary

theory. The feminist approach is connected to the notion of patriarchy, which highlights the fact that power

……………..

13

See footnote 2.

14

Radford, J. and Russell, D. (eds.), Femicide: The Politics of Woman Killing (Buckingham, Open University Press, 1992).

15

European Parliament resolution of 14 March 2017 on equality between women and men in the European Union in 2014-2015

(2016/2249(INI)). Available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=TA&reference=P8-TA-2017-0073&language=EN.

16

A/61/122/Add.1, In-depth study on all forms of violence against women, Report of the Secretary-General, p. 41 and p. 31.

17

A/61/122/Add.1, In-depth study on all forms of violence against women, Report of the Secretary-General, p. 31 and p. 47.

18

Available at http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-18-5904_en.htm.

19

Dawson, M. and Gartner R., “Differences in the characteristics of intimate femicides: the role of relationship state and relationship

status”, Homicide Studies, Vol. 2 (November 1998), pp. 378-399.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

25

is unequally distributed between women and men in society, meaning that violence is often used as a tool

by men to keep women under control.

20

The criminological approach to gender-related killing of women and girls, or “femicide”, has emerged in

the past two decades, to the extent that it is now used in epidemiology and public health research.

21

Criminological studies apply different terms to the analysis of this phenomenon, with some studies

applying the term broadly to indicate the killing of a woman,

22

while others focus on intimate partner

homicide, which they analyse as a subset of the broader homicide category.

23

Previously defined by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women as “the

culmination of pre-existing forms of violence, often experienced in a continuum of violent acts”, the notion

of “femicide” is inextricably linked to violence against women.

24

As such, the violence experienced by

women is influenced by conditions of gender-based discrimination, often reflected in patterns attributable

to gender-related killings of women, whereby structural factors influencing such discrimination are

encountered at the macrolevel of social, economic and political systems.

25

Due to the lack of a standardized definition of “femicide”, data collected by countries under this label are

not comparable and cannot be used for global or regional estimates to provide an indication of the scale

of this phenomenon. The way this type of offence is criminalized under a country’s legal system bears an

influence on the kind of data that is collected by the criminal justice system. Existing national reports on

“femicide” indicate that official data sometimes capture the number of cases of what could be broadly

considered gender-related killing of women and girls, and not necessarily the number of “femicide” victims

and subsequent disaggregations concerning the perpetrators, mechanism and context of killings related to

the number of victims.

The indicator “female victims of homicide perpetrated by intimate partners or family members” is used

instead, as this represents the only concept that has a standard definition across countries and, when

operationalized, that yields comparable data. This concept is standardized in the International

Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (ICCS).

26

The advantage of using the ICCS for the purpose of

recording and collecting statistical data relevant to this field is that the classification is built on a set of

behaviours and not legal definitions enshrined in criminal codes, as the latter differ across countries (see

box 5 for a comparison of data on the two indicators, “femicide” and “intimate partner/family-related

homicide”).

……………..

20

Corradi, C. et al., “Theories of femicide and their significance in social research”, Current Sociology, vol. 64, No.7 (International

Sociology Association, 2016), p. 5.

21

Ibid., p 7.

22

Campbell, J. et al., “Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: results from a multisite site case control study”, American Journal

of Public Health, vol. 93, No.7 (2003), pp. 1089-1097.

23

Stoeckl, H. et al., “The global prevalence of intimate partner homicide: A systematic review”, The Lancet, Vol. 382 (2013), pp. 859-865.

24

A/HRC/20/16, Report of the Special rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Rashida Manjoo (2012), para.

15.

25

Ibid., para. 17.

26

UNODC, International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (Vienna, 2015).

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

26

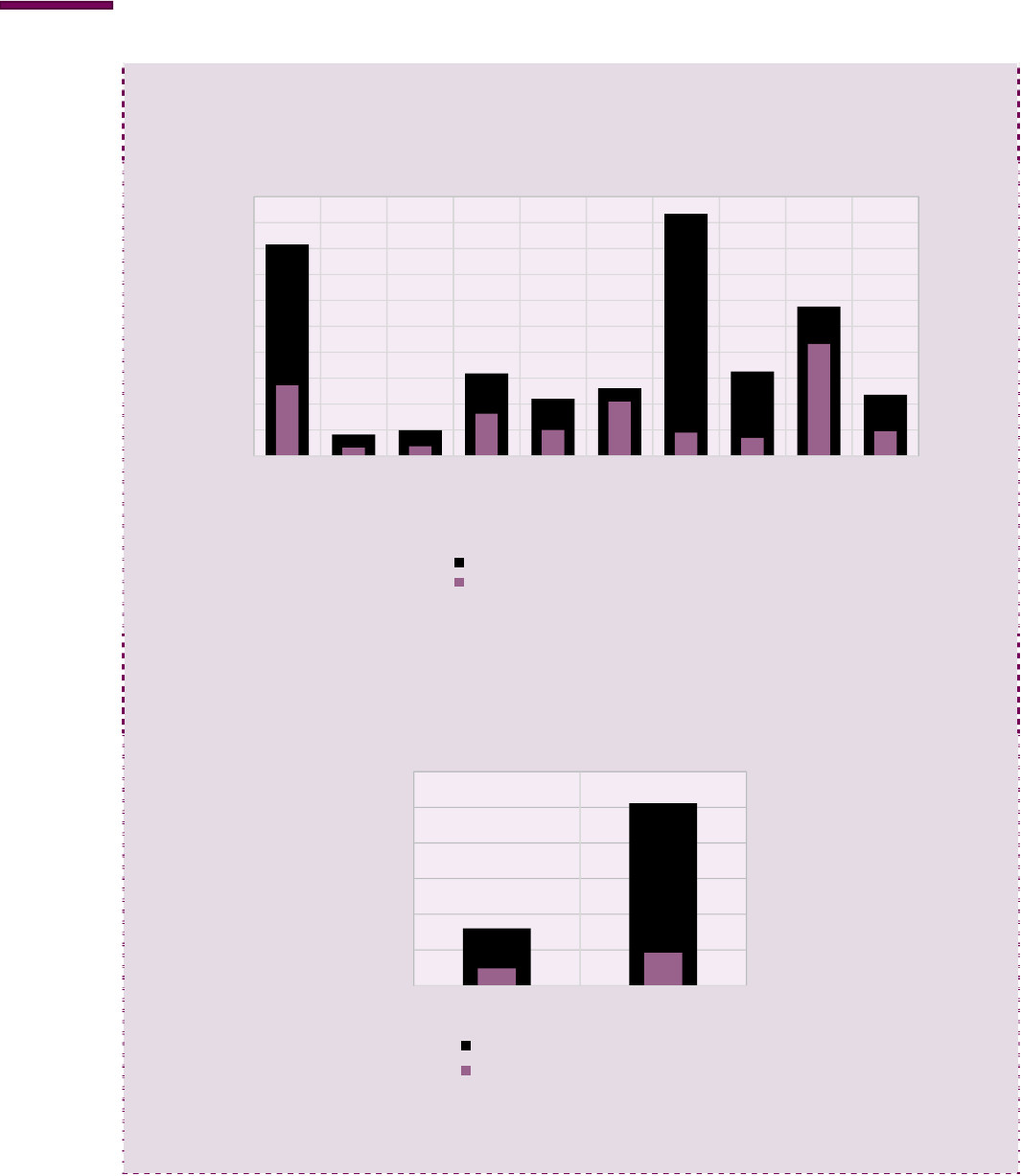

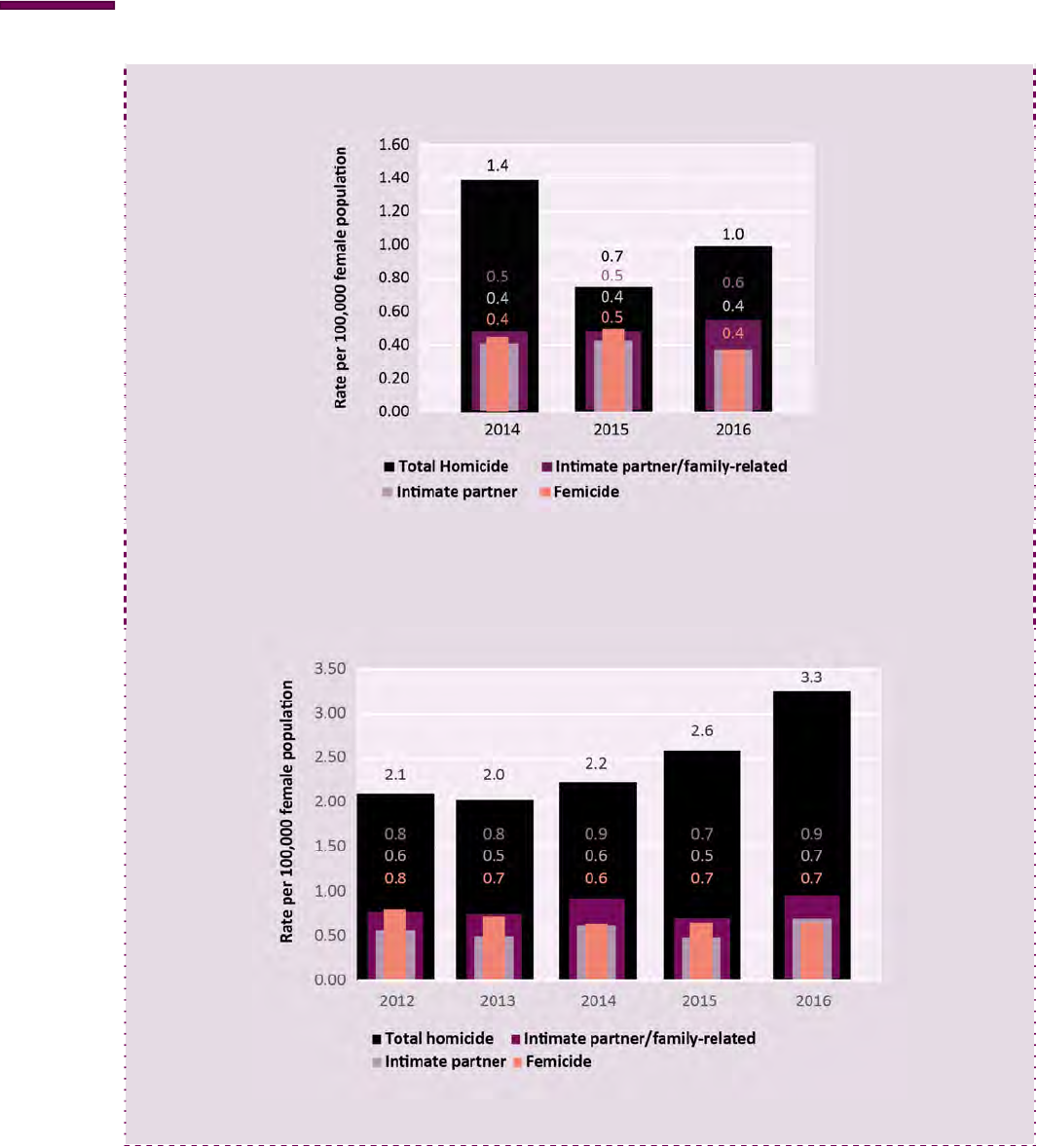

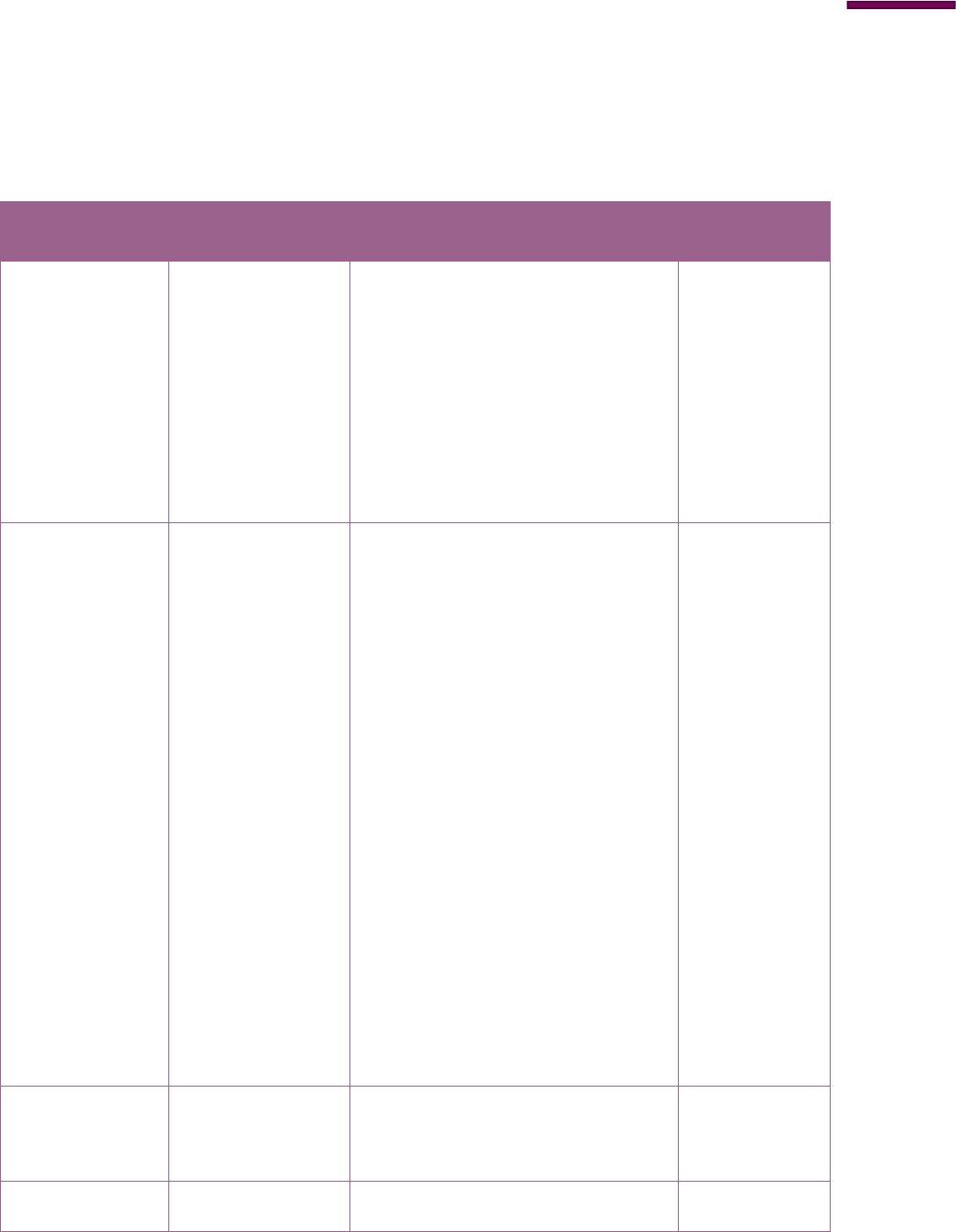

BOX 5: Comparison of data on “femicide”, female total homicide, and female

intimate partner/family-related homicide

The charts below compare different data associated with the notion of gender-related killing of women

and girls: the rates of female homicide, intimate partner/family-related homicide and “femicide” in

countries where all three types of data are available. There is not a consistent pattern in the comparison

of nationally-defined data on “femicide” and the standardized concept of intimate partner/family-related

homicide. This depends on how “femicide” is defined in national legislation and whether the definition

covers crimes committed in both the public and private spheres. In some countries, the two indicators

reveal the same values, in others the rate of “femicide” is higher or the rate of intimate partner/family-

related homicide is higher.

The analyses presented in the graphs below show that criminal justice recording practices regarding

“femicide” vary significantly across countries that have adopted legislation to criminalize the offence.

Legislation that addresses “femicide” helps to combat impunity and raise awareness in society of its gravity,

but data resulting from specific “femicide” legislation may misinterpret the level of the crime. Even though

certain countries have criminalized “femicide” as a separate criminal offence, in many instances such

crimes are still being recorded and prosecuted purely as homicide. This is because of obstacles encountered

during criminal proceedings and a lack of evidence in identifying a perpetrator or the circumstances in

which the crime was committed. In such cases, data recorded as “femicide” may underestimate the

number of gender-related killings.

For statistical purposes, looking at behaviours observed during the criminal act and the type of relationship

existing between victims and perpetrators, rather than how the act is coded in the criminal justice system,

provides measures that are more standardized across legislations and easier to interpret.

Comparison of levels

Rates of female total homicide, female intimate partner/family-related homicide, intimate partner

homicide and femicide, Latin America and the Caribbean (2016 or latest available year)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics; ECLAC.

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

7.0

Argentina

Barbados

Chile

Dominican

Republic

Ecuador

Grenada

Paraguay

Peru

Trinidad and

Tobago

Uruguay

Rate per 100,000 female population

Total female Intimate partner/family-related Intimate partner Femicide

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

27

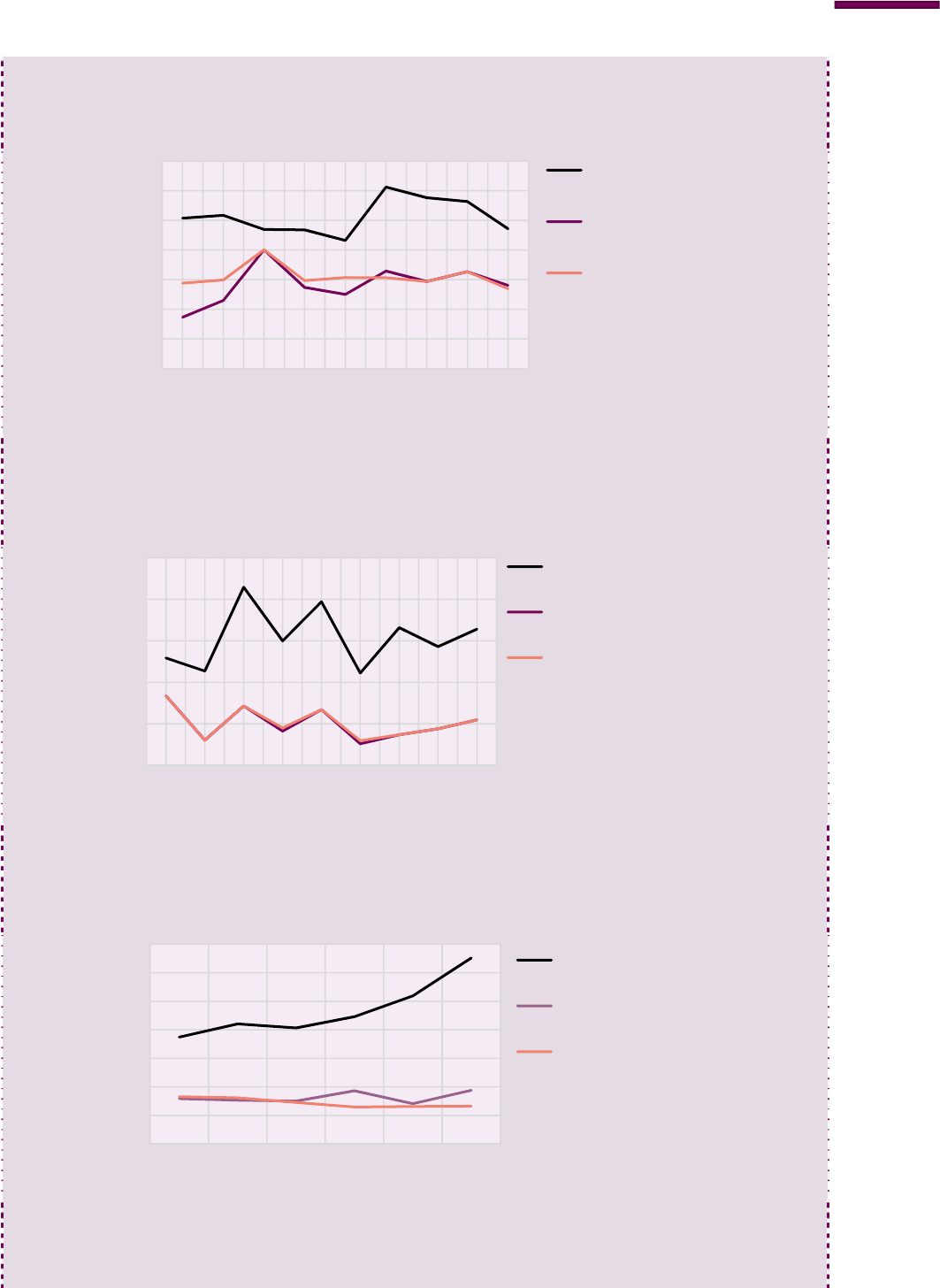

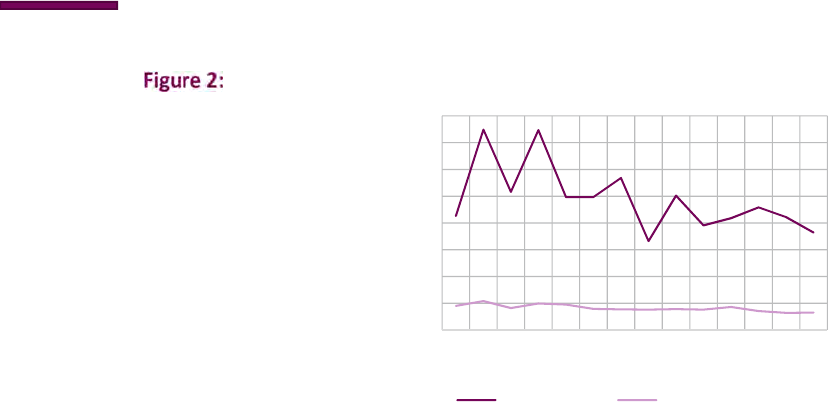

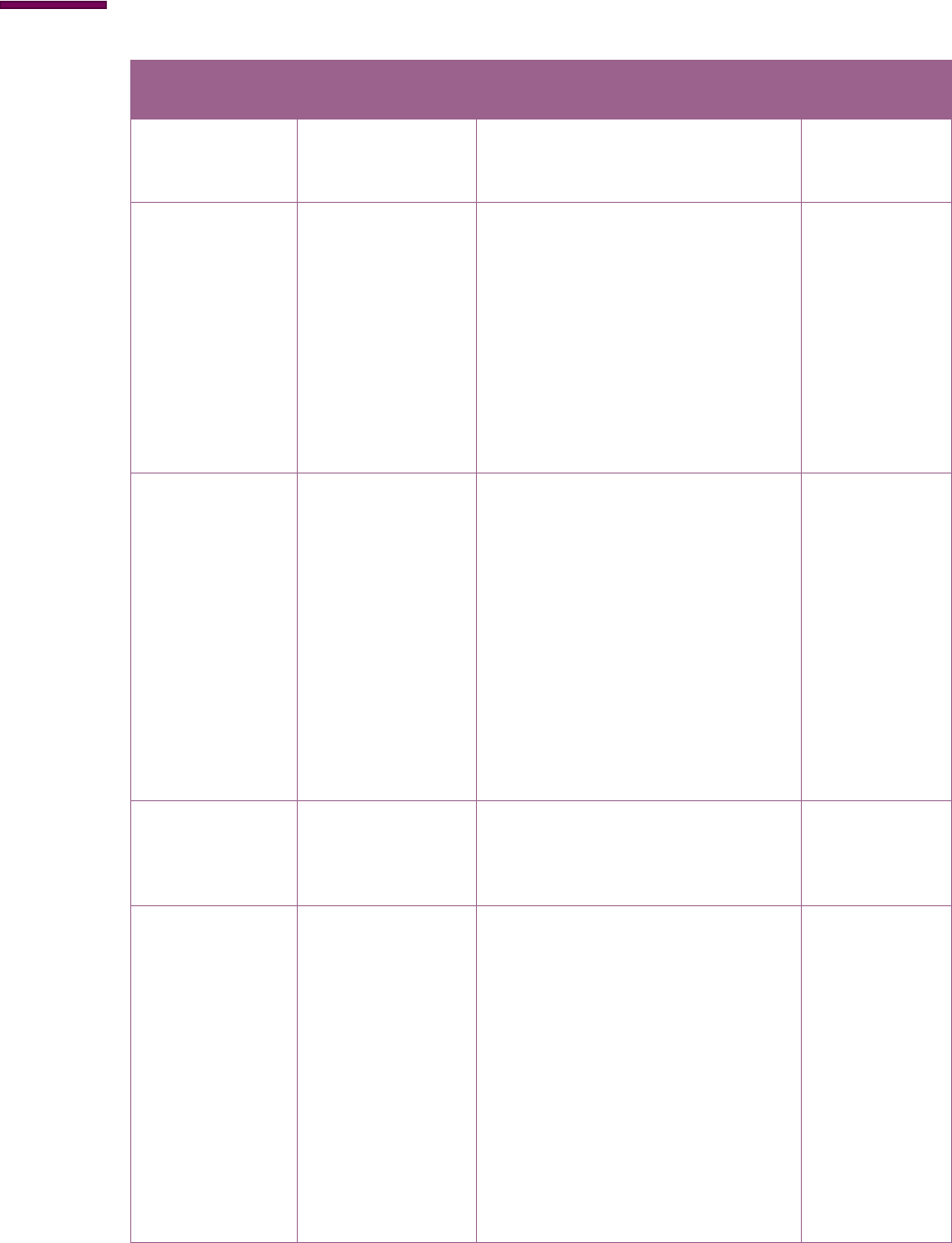

Comparison of trends

Rates of female total homicide, intimate partner/family-related homicide and femicide, Uruguay (2008-

2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics; ECLAC.

Rates of female total homicide, intimate partner/family-related homicide and femicide,

Trinidad and Tobago (2006-2015)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics; ECLAC.

Rates of female total homicide, intimate partner/family-related homicide and femicide,

Peru (2011-2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics; ECLAC.

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

Rate per 100,000 female

population

Total homicide

Intimate partner/

family-related homicide

Femicide

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

Rate per 100,000 female

population

Total homicide

Intimate partner/

family-related homicide

Femicide

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

Rate per 100,000 female

population

Total homicide

Intimate partner/

family-related homicide

Femicide

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

28

Rates of female total homicide, intimate partner/family-related homicide and femicide,

Chile (2014-2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics; Fiscalia Nacional: ECLAC.

Note: According to national legislation in Chile, only cases of femicide committed by current or former intimate partners are covered.

Rates of female total homicide, intimate partner homicide and femicide, Peru (2012-2016)

Source: UNODC homicide statistics; ECALC; Registro de Feminicidios del Ministerio Publico.

It is important to acknowledge that the indicator “intimate partner/family-related homicide” is not

exhaustive, as it does not capture all killings of women that may be considered under the label “femicide”,

excluding those homicides perpetrated outside the family sphere, such as some killings of female sex

workers or gender-related killings of women and girls in conflict situations. The availability of data on

homicides perpetrated outside the family sphere is limited and, given the nature and circumstances in

which such crimes are perpetrated, it is extremely difficult to identify the perpetrator, establish the

motivation behind the crime and record it. Where data on gender-related killing of women and girls outside

the family sphere are available, they show that the number of such killings outside conflict zones is very

small in comparison to the total number of killings resulting from intimate partner/family-related homicide.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

29

In Argentina and Peru, for example, where data on femicide/feminicide perpetrated both within and

outside the intimate partner or family sphere are collected by the Government, data indicate that the

majority of cases are committed by intimate partners or family members, with only a small percentage

being committed by persons unknown to the victim.

While comparable global and regional estimates on gender-related killings of women and girls can, to date,

only be based on intimate partner/family-related homicide, the description of different forms of gender-

related killing of women and girls below provides an overview of other forms of gender-related killing of

women and girls that occur outside the family sphere. The killing of female sex workers is presented as an

example of gender-related killing outside the family sphere, although it represents a small proportion of

all gender-related killings of women and girls, as indicated by data collected in Italy and Colombia.

BOX 6: United Nations undertakings aimed at preventing and combating

gender-related killing of women and girls

The United Nations General Assembly adopted two resolutions on gender-related killing of women and

girls in 2013 A/RES/68/191

27

and 2015 A/RES/70/176.

28

In 2014, UNODC convened an intergovernmental expert group meeting on gender-related killing of women

and girls, which discussed United Nations reports and information provided by Member States and civil

society organizations, making a number of recommendations, including on data collection and analysis.

29

The recommendations envisage practical measures to be undertaken by Member States in order to

improve prevention, investigation, prosecution and punishment of gender-related killing. They are

contained in the report of the Secretary-General on “Action against gender-related killing of women and

girls” (A/70/93).

30

The former United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women started to develop a knowledge

base around the topic of “femicide” and identified an extensive set of direct and indirect categories.

31

The

current United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women identified prevention of “femicide”

as an immediate priority of her mandate and emphasized the importance of collecting comparable data on

“femicide” disaggregated by the relationship between victims and perpetrators, age and ethnicity of

victims, together with information on the prosecution and punishment of perpetrators.

32

To this end, the

Special Rapporteur called upon Member States to establish “femicide/gender-related killing of women

watches”, which are mechanisms to be created at the national level, with the purpose of undertaking

systematic and detailed recording of “femicide”, in order to further develop preventive measures and guide

policymaking in this area.

33

Clustering gender-related killings of women and girls into

different forms

The following is a description of recognizable forms of gender-related killing of women and girls based on

the definition of “femicide” provided by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women

.

The prevalence of these different forms of killing may be global, regional or national:

34

……………..

27

A/RES/68/191.

28

A/RES/70/176.

29

For further information, see https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/justice-and-prison-reform/expert-group-meetings7.html.

30

Available at http://digitallibrary.un.org/record/797541/files/A_70_93-EN.pdf.

31

A/HRC/20/16, Report of the Special rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Rashida Manjoo (2012), para.

16.

32

A/HRC/32/42, Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences (2016), para. 45.

33

A/71/398, Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences (2016), para. 32.

34

A/HRC/20/16.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

30

1. Killings of women and girls as a result of intimate partner and domestic violence

Family homicides, also known as domestic homicides, include homicides perpetrated by intimate partners

or by other family members: siblings, parents, children, other blood relatives and other members of the

family. While in some countries the reported number of victims of intimate partner homicides and family

homicides represent almost equal shares of male and female victims, this pattern varies significantly across

countries.

As shown earlier in this study, in the context of gender-related killing of women within the family sphere

the perpetrators are often intimate partners. Intimate partner homicide refers to homicide committed by

a current or previous intimate partner. Criminological literature uses the term “uxoricide” to denote the

killing of a female intimate partner, although strictly speaking, the term is only applicable to female victims,

while “mariticide” is only applicable to male victims. However, given the fact that the vast majority of

intimate partner homicide victims include women, uxoricide often is often used to refer to the entire

category.

The prevalence of intimate partner violence has been well documented in recent decades.

35

Previous

studies on homicide point out that, without exception, females run a greater risk than men of falling victim

to intimate partner homicide.

36

The first Global Study on Homicide showed that in certain countries,

particularly in Europe, between 40 and 70 per cent of female victims of homicide may be killed by an

intimate partner.

Intimate partner violence in general victimizes women in particular and the same can be said about

homicides perpetrated by intimate partners. As mentioned earlier, in homicide cases when an intimate

partner was implicated, 82 per cent of the victims were women, while 18 per cent were men.

Intimate partner violence against women and girls is rooted in widely-accepted gender norms about men’s

authority within society in general and the family in particular, and men’s use of violence to exert control

over women.

37

Research shows that men and boys who adhere to rigid views of gender roles and

masculinity ̶ for example, the belief that men need more sex than women or that men should dominate

women, including sexually ̶ are more likely to use violence against a partner, among other negative

outcomes.

38

While available studies and their findings vary across different settings, some researchers have

identified ideas of male privilege and control among the main factors predicting the perpetration of

violence against women.

39

Key findings published by the World Health Organization indicate that men are

more likely to perpetrate violence if they have a limited education, a history of childhood maltreatment,

exposure to domestic violence against their mothers, harmful use of alcohol, unequal gender norms,

including attitudes that normalize the use of violence, and a sense of entitlement over women.

40

When it comes to non-lethal violence against women, sexual violence in adolescent relationships tends to

be associated with multiple individual and contextual factors, including exposure to adverse childhood

experiences, poor conflict-resolution and relationship skills, and norms that condone violence

……………..

35

Dobash R. et al., “Not an ordinary killer - just an ordinary guy: when men murder an intimate partner”, Violence against Women, vol.

10 (2004), pp. 577-605; Campbell, J.C., Sharps P. and Glass N., “Risk assessment for intimate partner violence”, Clinical Assessment of

Dangerousness: Empirical Contributions (New York, Cambridge University Press, 2000), pp. 136-157.

36

UNODC, Global Study on Homicide 2013 (Vienna, 2013); UNODC, Global Study on Homicide 2011 (Vienna, 2011).

37

Dunkle, K. L. and Jewkes, R., “Effective HIV prevention requires gender-transformative work with men”, Sexually Transmitted

Infections, Vol. 83(3), (2007) pp. 173-174.

38

Courtenay, W. H., “Better to die than cry? A longitudinal and constructionist study of masculinity and the health risk behavior of young

American men” Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 59(8-A), (1998) 3207.; Pulerwitz, J. and

Barker, G., “Measuring attitudes toward gender norms among young men in Brazil: Development and psychometric evaluation of the

GEM scale”, Men and Masculinities, vol. 10(3), (2008) pp. 322-338.

39

Jewkes, R.K., “Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention”, The Lancet, vol. 359 (2002), pp. 1423-1429.

40

See World Health Organization Violence against women-Key Facts. Available at http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-

sheets/detail/violence-against-women.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

31

perpetration.

41

The perpetration of sexual violence often emerges in the context of male peers who

demonstrate negative attitudes towards females, endorse bias-based

prejudices regarding homosexuality

and condone abuse perpetration. As regards male adolescents, perceived peer tolerance of sexual violence

in relationships may promote the individual likelihood of such behaviour and “may reduce comfort and the

ability to intervene when faced with negative behaviours among peers, contributing to a social climate that

enables such behavior”.

42

The vast majority of intimate partner homicides occur between heterosexual couples, most frequently

involving a male perpetrator and a female partner. Intimate partner homicide among same-sex couples,

bisexual and transgender couples also occurs, although much less frequently. Prior research in this area is

scarce, and has focused mostly on same-sex relationships. However, research in the United States found

that male same-sex intimate partner homicide occurs about 12 times more often than female same-sex

homicides.

43

This pattern was confirmed by another study that used a Chicago homicide dataset from the

period 1965-1990, in which 41 homicides involved male same-sex couples while 5 homicides involved

female same-sex couples.

44

A recent analysis in three European countries, found that a total of 2 per cent of all intimate partner

homicides involved male same-sex couples in both Finland and Sweden and 7 per cent involved male same-

sex couples in the Netherlands. None of the intimate partner homicides in the timeframe studied occurred

in female same-sex couples.

45

2. Honour-related killings of women and girls

Honour-related killings of women and girls are usually committed by family members when they consider

that the behaviour of female family members has brought shame on the family and needs to be sanctioned.

This kind of killing is a consequence of men’s domineering relationships with women.

46

Typical patterns of

behaviour that are perceived to transgress strict patriarchal gender roles include a young woman eloping

with a man other than the husband-to-be chosen by her family, and engaging in pre-marital relations.

Honour killings have also been reported when female rape victims have been killed by the male elders of

their families, including fathers, uncles and brothers, in order to spare the family the shame associated

with the stigma of sexual violence suffered by unmarried women.

47

Available data on honour killings are scarce, as such crimes often go unrecorded and unreported.

Nevertheless, existing studies indicate that honour killing remains a practice that is encountered in parts

of Asia, in particular. When perpetrated in rural areas, such crimes are particularly difficult to record, yet

efforts have been made to reveal the scope of this problem in certain countries. In Afghanistan, for

example, a National Inquiry Report published by the Government Human Rights Commission estimated

that some 243 cases of honour killing had occurred between April 2011 and August 2013.

48

The risk of

falling victim to such crimes was higher among youth and the middle-aged, and when the victim was an

unmarried girl, the crime was usually committed by male family members; although to a lesser extent, it

may also have been perpetrated by female family members.

49

……………..

41

Engendering healthy masculinities to prevent sexual violence: Rationale for and design of the Manhood 2.0 trial, Contemporary Clinical

Trials 71 (2018) 18-32. Available at https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=https://promundoglobal.org/wp-

content/uploads/2018/06/PIIS1551714418300296.pdf.

42

Ibid.

43

Glass, N. et al., “Female-perpetrated femicide and attempted femicide: a case study”, Violence against Women, 10 (2004), pp. 606-625.

44

Block, C. R. and Christakos, A., “Intimate partner homicide in Chicago over 29 years”, NCCD news, 41(4) (1995), pp. 496-526.

45

Liem, M.,et al., “Intimate partner homicide in Europe, Colloque International sur l'Homicide” (Paris, June 2017).

46

National Inquiry report on: factors and causes of rape and honour killing in Afghanistan, 2013, Afghanistan Human Rights Commission,

p. 8.

47

Puttick, M., The Lost Women of Iraq: Family-based Violence During Armed Conflict (Minority Rights Group International, 2015), p. 26.

48

National Inquiry report on: factors and causes of rape and honour killing in Afghanistan, 2013, Afghanistan Human Rights Commission,

p. 4.

49

Ibid.

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

32

Anecdotal evidence provided by news outlets and human rights commissions in some Asian countries have

indicated that many victims of honour killing were married women and the perpetrator was often the

husband. The motive for the killing was frequently linked to the victim’s illicit affairs, or her choice of

marriage. In certain instances, other members of the family, such as parents, siblings, uncles, in-laws, other

distant relatives or even neighbours and acquaintances were responsible for the crimes. Mechanisms used

for committing honour killings often involved firearms and, to a lesser extent, blunt objects and

strangulation, beating and burning; the majority of victims were not employed.

3. Dowry-related killings of women

Referring to instances in which brides are killed or driven to commit suicide after being subjected to

continuous harassment and abuse by the groom’s family in an effort to extort dowry payment or increased

dowry involving cash or goods,

50

dowry-related killings of women are widely reported in South-Asian

countries. A common manifestation of this practice is the burning of the wife, such incidents often being

presented to criminal justice authorities as accidents caused by an exploding kitchen stove.

51

Despite the

fact that many of the countries in which dowry deaths are prevalent have adopted legislation banning the

practice of dowry, it remains embedded in religious and cultural traditions in South-Asian countries.

52

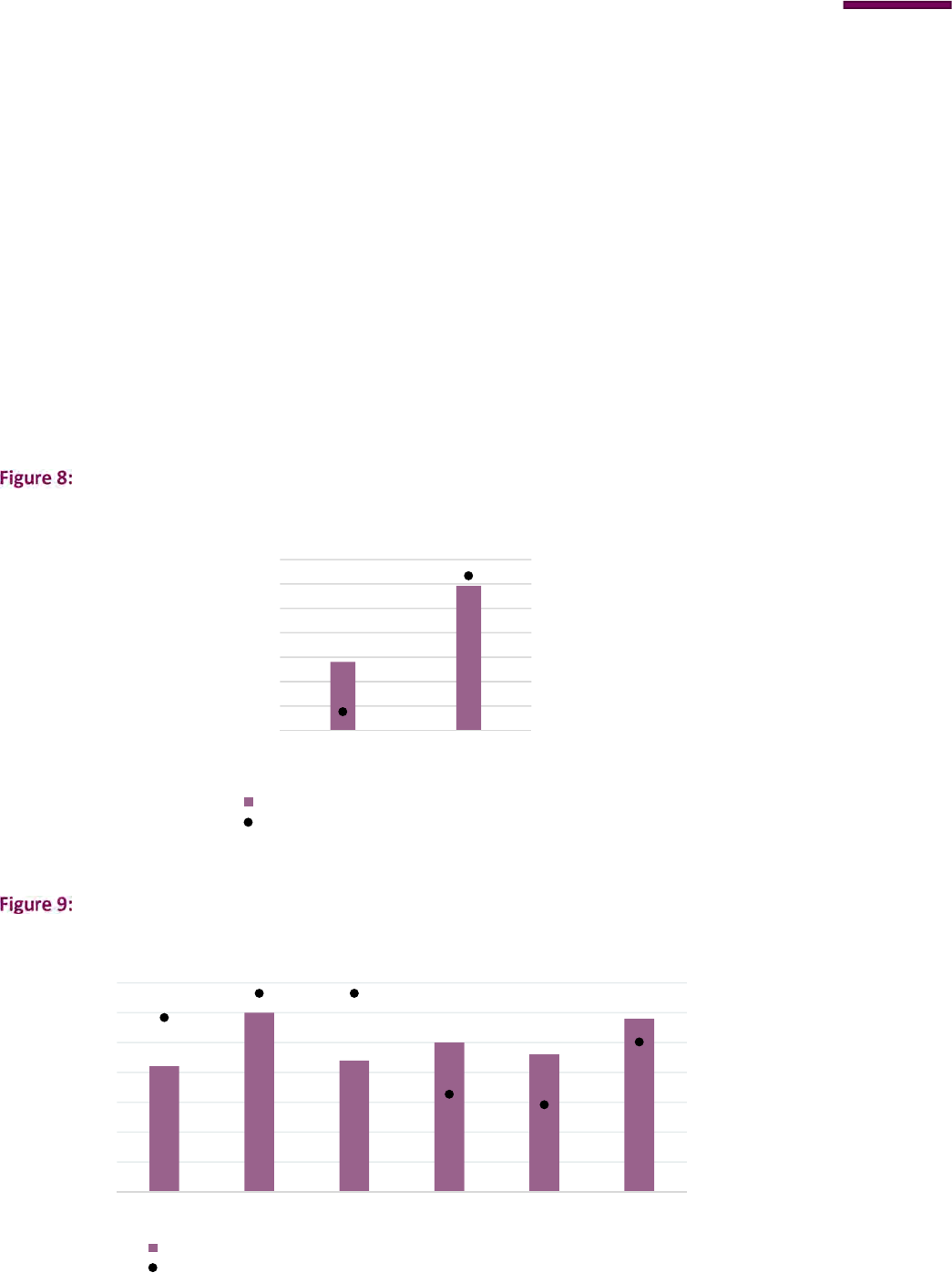

BOX 7: Dowry-related killings in India

Dowry deaths constitute a unique category of deaths in India’s Penal Code, which has been amended in

recent decades to specifically deal with dowry-related violence.

53

The offence “dowry death” was

introduced into India’s Penal Code in 1986 as section 304-B by an amendment to the Dowry Prohibition

Act. Section 498-A of India’s Penal Code penalizes any kind of harassment by a husband’s family; the penal

provisions of section 304-B may apply in any unnatural death of a woman within seven years of marriage.

In cases where a woman commits suicide as a result of harassment by her husband or his family, non-

dowry-related section 306 is applicable. In cases of dowry-related suicide, both sections 304-B and 306 are

applicable. Available data on dowry-related killings from the National Crime Records Bureau indicate that

female dowry deaths account for 40 to 50 per cent of all female homicides recorded annually in India,

representing a stable trend over the period 1999 to 2016. Despite legislation adopted by the Indian

Government in 1961, prohibiting the payment of dowry,

54

the practice continues throughout the country

and dowry deaths continue to account for a substantial share of all female homicides.

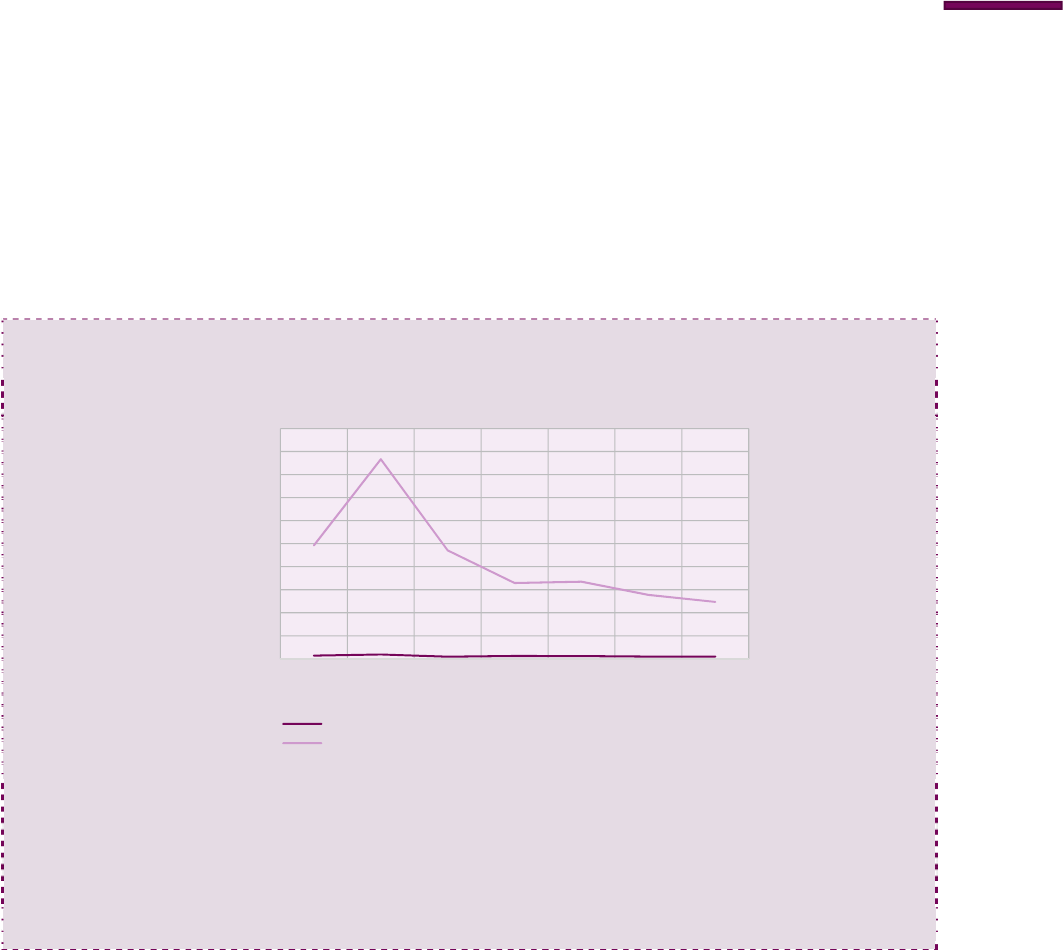

Rates of female homicide and dowry-related death, India (1999 ̶ 2016)

Source: National Crime Records Bureau, India.

……………..

50

A/HRC/20/16, Report of the Special rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Rashida Manjoo (2012), para.

56.

51

Saha, K. K. and Mohanthy S., “Alleged dowry death: a study of homicidal burns”, Medicine, Science and the Law, vol. 46 (2006), pp. 105-

111.

52

Harmful traditional practices in three countries of South Asia: culture, human rights and violence against women, Gender and

Development Discussion Paper Series No. 21 (Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, 2012).

53

Belur, J., Tilley, N., Daruwalla, N., Kumar M., Tiwari V., and Osrin D. (2014), The social construction of “dowry deaths”, Social Science

and Medicine, vol. 119, pp. 1-9.

54

For more information, see Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961.

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

Rate per 100,000

female population

Female

homicide

Dowry

deaths

Gender‐relatedkillingofwomenandgirls

33

4. Killings of women in the context of armed conflict

The practice of targeting women in an armed conflict and the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war

has been documented in several reports published by the United Nations.

55

The systematic use of rape

against women is used to destroy the fabric of societies, as women who have suffered conflict rape are

often shunned and ostracized by their communities. Mass rapes and killings of women and girls were

documented in the conflicts in Rwanda in 1994 and more recently in the Democratic Republic of the

Congo.

56

Mass killings of Yazidi women by Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) are reported to have

taken place in recent years in Iraq’s Sinjar province, after several mass graves were discovered.

57

Killings of women in conflict are often preceded by sexual abuse, whereby women are sometimes killed

together with their families; in other instances they are forced into slavery and subjected to sexual abuse.

58

Although it is not possible to accurately record gender-related killings of women and girls during armed

conflict, it is important to acknowledge that sexual violence, kidnapping and enslavement accompanied, or

preceded, by intentional killing has been systematically used against women in times of conflict. For this

reason, these unrecorded gender-based killings of women and girls may substantially elevate the global

number of victims of this type of homicide. The ICCS also considers intentional killings of civilians, i.e. non-

combatants, during armed conflict as intentional homicides, irrespective of whether they are committed

by combatants or non-combatants.

59